I am always on the look out for books that will hook my readers and mentor texts that will inspire my writers.

But when I saw the title The Radical Element, 12 Stories of Daredevils, Debutantes & Other

It’s never too early to give girls hope.

Dauntless Girls, I thought of my own three daughters, my daughter-in-law, and my two granddaughters. (Well, not so much the debutantes, but definitely the daredevils and the dauntless.)

We need books where our girls see themselves –where they feel empowered to take on the world. In a brochure I got from @Candlewick, it states:

To respect yourself, to love yourself, should not have to be a radical decision. And yet it remains as challenging for an American girl to make today today as it was in 1927 on the steps of the Supreme Court. It’s a decision that must be faced when you’re balancing on the tightrope of neurodivergence, finding your way as a second-generation immigrant, or facing down American racism even while loving America. And it’s the only decision when you’ve weighed society’s expectations and found them wanting.

So today, I write to celebrate the book birthday of The Radical Element edited by Jessica Spotswood.

Jessica writes:

. . . Merriam-Webster’s definitions of radical include “very different from the usual or traditional” and “excellent, cool.” I like to think our heroines in these twelve short stories are both. Our radical girls are first- and second- generation immigrants. They are Mormon and Jewish, queer and questioning, wheelchair users and neurodivergent, Iranian- American and Latina and Black and biracial. They are funny and awkward and jealous and brave. They are spies and scholars and sitcom writers, printers’ apprentices and poker players, rockers and high-wire walkers. They are mundane and they are magical.

. . .

It has been my privilege to work with these eleven tremendously talented authors, some of whom are exploring pieces of their identities in fiction for the first time. I hope that in some small way The Radical Element can help forge greater empathy and a spirit of curiosity and inclusiveness. That, in reading about our radical girls, readers might begin to question why voices like these are so often missing from traditional history. They have always existed. Why have they been erased? How can we help boost these voices today?

I have only read a few of these stories so far, but they are a wonderful blend of adventure and courage.

Here’s what three of the 12 authors have to say about their stories:

From Dhonielle Clayton, “When the Moonlight Isn’t Enough”:

1943: Oak Bluffs, Massachusetts

What encouraged you to write about this moment in history?

I wanted to write the untold stories of hidden black communities like the one in Martha’s Vineyard. I’m very fascinated with black communities that, against all odds and in the face of white terrorism, succeeded and built their own prosperous havens. Also, World War II America is glamorized in popular white American culture, however, we learn little about what non-white people were doing during this time period.

In researching this topic, did you uncover any unexpected facts or stories?

I didn’t find as much as I wanted because historians focused on white communities and the war effort, leaving communities of color nearly erased. I had to rely on living family members that experienced this time period and a few primary sources detailing what life was like for black nurses in the 1940s.

How do you feel like you would fare during the same time period?

The one thing I trust is that black communities have been and will always be resourceful. Accustomed to being under siege, we have developed a system of support. I think I would’ve fared just fine.

From Sara Farizan, “Take Me with U”:

1984: Boston, Massachusetts

What encouraged you to write about this moment in history?

I’ve always been fascinated with the 1980’s. Even with all its faults, it is the period in time that stands out for me most in the 20th century. The music, the entertainment, the politics, the fear and suffering from the AIDS virus, the clothes, and the international events that people forget about like the Iran/Iraq war.

In researching this topic, did you uncover any unexpected facts or stories?

It was hard to look back on footage from news broadcasts about the Iran/Iraq war. I felt embarrassed that it seemed this abstract thing for me when really my grandparents came to live with my family in the States during the year of 1987 to be on the safe side. I was very young, and didn’t think about why they had a year-long visit, but looking back, I can’t imagine how difficult that must have been for them. Fun not so heavy fact: Gremlins, Ghostbusters, Purple Rain came out in the summer of ’84. And so did I!

How do you feel like you would fare during the same time period?

I think I would know all the pop culture references and my hair is already big and beautiful so that would work out great. My Pac-Man and Tetris game is strong, so I’d impress everyone at the arcade. However, I’m not down with shoulder pads and I don’t know if I would have been brave enough to come out of the closet back then.

From Mackenzi Lee, “You’re a Stranger Here”

1844: Nauvoo, Illinois

What encouraged you to write about this moment in history?

My story is set in the 1840s in Illinois and is about the Mormon exodus to Utah. I was raised Mormon, and these stories of the early days of the Church and the persecution they suffered were very common place. It took me a while to realize that, outside of my community, no one else knew these stories that were such a part of my cultural identity. I wanted to write about Mormons because its such a part of my history, and my identity, but also because, when I was a kid, there were no stories about Mormons. There are still no stories about Mormons–it’s a religious minority that has been largely left out in our current conversations about diversifying our narratives.

In researching this topic, did you uncover any unexpected facts or stories?

Ack I wish I had a good answer here! But honestly not really–I already knew so much of what I wrote about because I’d gone to a Mormon church throughout my youth.

How do you feel like you would fare during the same time period?

Badly! The Mormons went through so much for their faith, and as someone who has had a lot of grief as a result of the religion of her youth, I don’t know if I could have handled having a faith crisis AND being forced from my home multiple times because of that faith. Also cholera and heat stroke and all that handcart pulling nonsense is just. too. much. I didn’t survive the Oregon Trail computer game–no way I’d survive an actual trek.

Amy Rasmussen teaches readers and writers at a large suburban high school in North TX. She loves to read and share all things books with her students. In regards to this post, Amy says, “It’s Spring Break for me, and I’ve been idle. Kinda. Three of my grandkids arrived at the spur of the moment, so I’ll use that as an excuse for posting late today.” Follow Amy @amyrass and @3TeachersTalk.

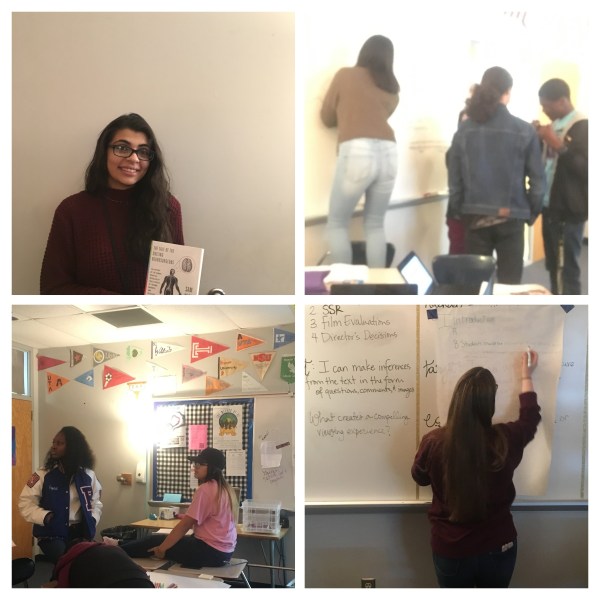

can we do things even better? How can we reach more kids? How can we ensure that every student feels connected to their school and their teacher? Don’t misunderstand me- I work with the best teachers around, who love kids and are passionate about the work they are doing in their classrooms. However, we can always do more and get better, right?

can we do things even better? How can we reach more kids? How can we ensure that every student feels connected to their school and their teacher? Don’t misunderstand me- I work with the best teachers around, who love kids and are passionate about the work they are doing in their classrooms. However, we can always do more and get better, right? important aspects- talking with our students. This area was a big learning curve for us. The tendency is to think that having a teacher table or holding daily student conferences is an elementary concept, but in reality it’s what’s best for students at all levels. The teachers I work with would say that conferencing with students has been a game changer. They know their students strengths and weaknesses in reading and writing better than before, and they are able to target specific skills that each student needs.

important aspects- talking with our students. This area was a big learning curve for us. The tendency is to think that having a teacher table or holding daily student conferences is an elementary concept, but in reality it’s what’s best for students at all levels. The teachers I work with would say that conferencing with students has been a game changer. They know their students strengths and weaknesses in reading and writing better than before, and they are able to target specific skills that each student needs.

function in perpetual chaos. Every day I whack-a-mole them into their current book, notebook work, mentor text, draft, or just away from their phones.

function in perpetual chaos. Every day I whack-a-mole them into their current book, notebook work, mentor text, draft, or just away from their phones. That day, the SparkNotes summary of the first chapter of Fahrenheit 451° (one book circle choice) was their writing prompt. There was some confusion: Were they supposed to write about whether they were going to choose that book? Or to predict what the book might be about? This prompt is like any other daily writing, I told them. Just write what it brings to mind.

That day, the SparkNotes summary of the first chapter of Fahrenheit 451° (one book circle choice) was their writing prompt. There was some confusion: Were they supposed to write about whether they were going to choose that book? Or to predict what the book might be about? This prompt is like any other daily writing, I told them. Just write what it brings to mind.

There were about two weeks of school when we came back that I wondered if I was doing something wrong. It seemed like I had WAY too much time on my hands, and I wasn’t quite sure if I was just forgetting about responsibilities, and therefore shirking them in some way, or if I actually was managing my time better.

There were about two weeks of school when we came back that I wondered if I was doing something wrong. It seemed like I had WAY too much time on my hands, and I wasn’t quite sure if I was just forgetting about responsibilities, and therefore shirking them in some way, or if I actually was managing my time better.