Okay, I stole the inspiration for this post’s title from the late, great Bob Ross, but if the tree (or daffodil) fits, then I’m good with sappy wordplay. AP Literature can feel dark at times because many of the texts we read deal with death, loss, and desire. That’s why I look forward to the beauty and humor found in our texts and with each other in our class. The Romantic literary era provides wonderfully rich, dark, gothic themes, but it also provides opportunities for students to think about how they connect with nature and beauty. Often, it reminds them that they’re not taking time to relax, reflect on beauty, or enjoy some downtime away from small screens.

Okay, I stole the inspiration for this post’s title from the late, great Bob Ross, but if the tree (or daffodil) fits, then I’m good with sappy wordplay. AP Literature can feel dark at times because many of the texts we read deal with death, loss, and desire. That’s why I look forward to the beauty and humor found in our texts and with each other in our class. The Romantic literary era provides wonderfully rich, dark, gothic themes, but it also provides opportunities for students to think about how they connect with nature and beauty. Often, it reminds them that they’re not taking time to relax, reflect on beauty, or enjoy some downtime away from small screens.

- We began by reading William Wordsworth’s “I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud” – a wonderful poem for traditional analysis. More importantly, it serves as a great mentor text to think about those places upon which we reflect when we’re feeling down. Here’s Wordsworth’s poem:

“I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud,” by William Wordsworth:

I wandered lonely as a cloud

That floats on high o’er vales and hills,

When all at once I saw a crowd,

A host, of golden daffodils;

Beside the lake, beneath the trees,

Fluttering and dancing in the breeze.

Continuous as the stars that shine

And twinkle on the milky way,

They stretched in never-ending line

Along the margin of a bay:

Ten thousand saw I at a glance,

Tossing their heads in sprightly dance.

The waves beside them danced; but they

Out-did the sparkling waves in glee:

A poet could not but be gay,

In such a jocund company:

I gazed—and gazed—but little thought

What wealth the show to me had brought:

For oft, when on my couch I lie

In vacant or in pensive mood,

They flash upon that inward eye

Which is the bliss of solitude;

And then my heart with pleasure fills,

And dances with the daffodils.

- We analyzed the poem together, noting its craft and themes. We discussed a variety of ideas: the few visible stars in our city’s night sky compared the multitude of stars that can be seen in the country, how the simple experiences in life can be the most profound, and the importance of having a “happy” or safe place.

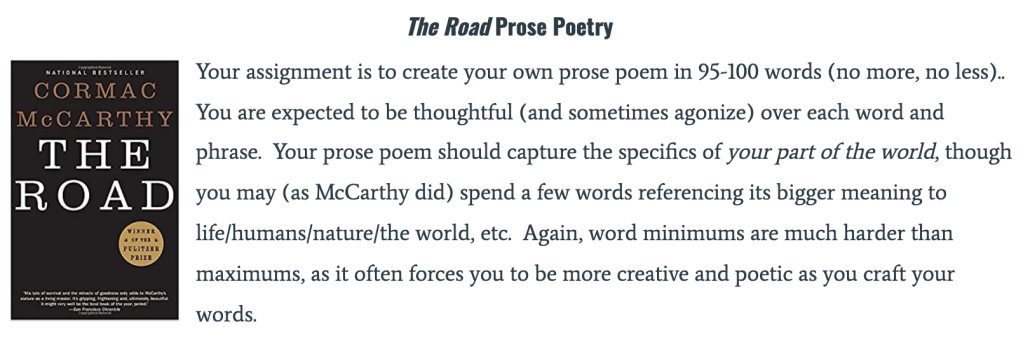

- We talked about the genre of poetry as a vessel for this beautiful message, and we discussed how we might capture the same beauty in prose. The word “prose” still scares many of my students, so we talked about what that meant. One student asked if prose is similar to the personal narratives they wrote for standardized tests when they were younger, so we also talked about the test-genre and its relationship to more authentic writing. (Incidentally, there’s an idea for a whole other blog post!)

- I shared two prose pieces about happy places of my own, and the students analyzed the craft in those. We discussed the literary devices present and their effects in the piece. They talked about the song lyrics woven into “Funkytown” and how the diction becomes darker as I leave my “happy place” – the roller rink. They talked about the sibilance in “Whither Thou Goest” that correlates with the river that winds like a snake below the mountain, the color imagery, and biblical allusions. It is always magical when we write with our students, and the fact that I shared myself with them made them feel more comfortable to write honest pieces of their own.

- Ultimately, I challenged them to write about a literal or figurative “happy place” of their own. It could be a physical place or a state of mind. I challenged them to play with language. There was no length requirement, but they were to label 5 different literary devices they employed.

- Just as I weaved song lyrics through one of my pieces, some students incorporated poetry, lyrics from a musical, and even lines from a movie into theirs. Others preferred more straight-forward, concise prose. Some wrote very poetic prose. In every case, however, their voices shone! The results were some of the best writing I’ve read from them all semester.

- The next step is to discuss how they can use their voice and their writing strengths in their academic writing. I once heard an AP Literature teacher say that there was “no time to have students write their own poetry in the course” and that worse yet, he’d “have to read it.” I have always felt sorry for that man. In my experience, it is the best way for students to find and hone their writing voices, learn about literary devices in an authentic way, and for teachers to foster a love of writing in their students. With the next mentor-inspired text, I will have them analyze their own writing.

Here are a couple of student samples from this assignment, unaltered by me, used with their consent:

By Jake (3/3/2019)

I do not feel at home in Texas. The land is flat, the weather is tourettic; these gargantuan skies transmogrify from benevolent baker to dekiltered, frenetic assailant mile by mile, hour by hour, even. I take it back: I appreciate the tumult above the flats of Texas. It compensates for the, well, flatness. I could go on and on about how I would rather adore the rapturous peaks of my birth state, Colorado, how each and every inch stirs within a kindred connection that I experience nowhere else in the country. I could go on and on about how the saltine winds along the coasts of Washington corrode my worries into a whelming paste, yet these are, regrettably, far away places. I frequent these happy places, sure, but my memories elapse more time than that which I have spent in these places. Music allows me to carry these places around with me, wherever I may roam.

“Bat Out Of Hell” by Meat Loaf forever holds a motorcycle to Colorado, as I was truly deafened by Meat’s foghorn vocals and personality for the first time in a balmy summer night’s drive through some valley whose name escapes me. Led Zeppelin’s “D’yer Mak’er” speaks to me of foot-slicing clamshell beachfronts, Dad trying his damndest to deafen me with Led Zeppelin in the rental car, and whiling hours drowned on that driftwood deck. I find the King in me whenever I pick up that there hairbrush in the bathroom and belt, belt as freely as the mighty Mississippi River flows. “Patch It Up,” “Blue Suede Shoes,” “Steamroller Blues,” and “Fever” purr and yelp around the room, terminally ill with suave, when I’m feeling up. “If I Can Dream,” “Bridge Over Troubled Water,” “American Trilogy,” and “You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feelin’” croon and boom through the hallways when I’m feeling like the sky above. I am as much myself while belting Elvis to pictures on the wall and motes of dust as I am writing poetry to no one in particular.

However, if my musical mind is a mountain, Elvis Presley makes up little more than the babbling brook rushing between the rocks that I scrub off my worries in. Meat Loaf is the foothills, the base upon which rests my musical perspective. Sturgill Simpson is the renegade wind that whistles through the hills, tossing me hither and thither as I make my merry way up the mountain path. In the forest of rock n’ roll, the wind takes on more of a Led Zeppelin flavor, rustling the Beatle pine needles. The rocks upon which I scrape my hiking boots are the bones of the bands that built the tastes I enjoy today. Bands like Nirvana, Styx, and Deep Purple, which once shone me the colors with which I view the forest today, yet get trampled nowadays in my search for the more exotic indie elixirs. If my musical mind is truly a mountain, then surely for every stone this metaphor turns over lie another taunting ten.

Then music, unlike any physical happy place, must surely forever evolve, must be at the whim of the beholder and drive the behest of the spirit, must sculpt the mountains of the mind and scythe paths for one to meander, to sprint, to cower, praise, sleep upon, to stray from. Well, it holds this precedent to me, at least. Music has also upheld the standard upon which I interact with other people. What sets music apart from any happy place is that music builds the places into the palaces of peace that they are in my mind.

By Lung (3/4/2019) *Lung is an English-language Learner!

On Jan. 20th, 2019, I experienced a phenomenon when the world stopped spinning, and the universe halted to a finite. I have had many perfect memories in my life, but not as unrivaled as this one. I’ve never felt more desperate for time to stand still and for picture-perfect moments to last. I lived only in that moment: cherished and content and peaceful.

It was my two year anniversary with my boyfriend who is more like my partner in crime than a lover. He took me to Gussie Field Watterworth Park in Farmers Branch, Texas to share a “treasure” that he found. Although I was skeptical about going to a park on an evening when the weather dropped as low as 32 degrees, I still followed him, ready for an adventure. When we arrived at our destination, I opened the passenger door only for the harsh wintry breeze to slap me into regret. I scanned the scenery to recognize that we were the only people insane enough to occupy a park when the weather could freeze a person whole. The flowers have wilted into brown garments, and even sheets of ice were floating lazily on the pond. I was soon disrupted of my thoughts, when he grabbed my hand and pulled me into the middle of one of the many trails toward what looked like a box from afar. As he stopped and let go of my hand, I was face to face with a tiny wooden cabinet covered in a peeling paint of baby blue. It contained many books of different genres on its mini shelves, and I looked up at him in surprise. Knowing he wasn’t one to read but to kick soccer balls, I was even more astonished when I saw how his eyes twinkled like stars by the sight of books. After we both grabbed a book, we sat down on one of the wooden benches to enjoy each other’s presence and read silently as I drowned in peace.

Soon after, when the sun began to set, the sky was tinted with an array of pink, orange, and yellow. The clouds boasted with mystical colors and the pale glow of the moon was beginning to show. Hand in hand, we walked back to the wooden box to return the books to their shelter. As we placed them onto a shelf, he pulled my shivering body into his jacket and wrapped his arms around me. As I placed my head onto his chest, from deep inside my chest, through every cell of my body, the warmth welcomed me like an old friend. There we stood, under the glorious paint, two kids ready to face the world. Then I realized, it really was a treasure.

Polysyndeton

Personification

Hyperbole

Imagery

Simile

Amber Counts teaches AP English Literature & Composition and Academic Decathlon at Lewisville High School. She believes in the power of choice and promotes thinking at every opportunity. She is married to her high school sweetheart and knows love is what makes the world go around. Someday she will write her story. Follow Amber @mrscounts.

Okay, I stole the inspiration for this post’s title from the late, great Bob Ross, but if the tree (or daffodil) fits, then I’m good with sappy wordplay. AP Literature can feel dark at times because many of the texts we read deal with death, loss, and desire. That’s why I look forward to the beauty and humor found in our texts and with each other in our class. The Romantic literary era provides wonderfully rich, dark, gothic themes, but it also provides opportunities for students to think about how they connect with nature and beauty. Often, it reminds them that they’re not taking time to relax, reflect on beauty, or enjoy some downtime away from small screens.

Okay, I stole the inspiration for this post’s title from the late, great Bob Ross, but if the tree (or daffodil) fits, then I’m good with sappy wordplay. AP Literature can feel dark at times because many of the texts we read deal with death, loss, and desire. That’s why I look forward to the beauty and humor found in our texts and with each other in our class. The Romantic literary era provides wonderfully rich, dark, gothic themes, but it also provides opportunities for students to think about how they connect with nature and beauty. Often, it reminds them that they’re not taking time to relax, reflect on beauty, or enjoy some downtime away from small screens.