“The soul of the brave warrior rising slowly with the smoke…” Taylor Mali

For the last several years, my first writing study in January with eighth graders has consisted of what I refer to as food narratives. Many thanks to Karla Hilliard for inspiring me with this idea originally!

Over time, I’ve learned that food writing is a love language of sorts for teenagers.

Students soon discover that in writing about food, though meals are significant, it’s the memories evoked that matter. We’re remembering not only the Christmas cheesy potatoes, but the person who made them and the conversations that we savored around the table. Meals are like lighthouses on the shorelines of our lives, and writing about food ignites the light and spreads it as we choose sensory details that give our writing color and meaning.

On Martin Luther King Jr., Day, a day that memorializes a man who crossed racial and religious divides by speaking the common language of love, I’m reflecting on how often teenagers are marginalized, how frequently they are overlooked by a culture that tags them as unmotivated, relationally awkward, shackled to their phones, and the list goes on. I’ve been thinking about what it means to be an unsung hero. Webster’s definition of “unsung” is as follows:

unsung adjective

un·sung | \ ˌən-ˈsəŋ \

Definition of unsung

1.not sung

2. not sung meaning not celebrated or praised (as in song or verse)

an unsung hero

Last week, I wrote the following narrative for my students about a season in my life when a high risk pregnancy required bed rest, and I found myself confined to a hospital room for months. On one level, it’s a story of struggling to consume the number of calories required to support multiple babies–but it’s also about the endurance of love, and what a difference a visit from my theatre students made. They were my unsung heroes, and my current students are also givers of courage and hope in a world that is often forbidding and constantly changing.

Unsung Heroes

March 29th, 2004

9 AM: I wake up thinking: “Today is going to be awful.” Dr. Rightmeier invades my room, perfectly clinical in his long white coat, stethoscope hanging loosely around his neck like a lifeguard’s whistle. He’s pacing, frustrated.

“You can’t possibly overindulge.”.

“Eat whatever you want. Eat THIS,” he says, holding up a supersized Hershey bar. “You should be taking in more calories.”

I CAN’T! That’s what my mutinous mind is thinking. My doctors increased my dosage of magnesium sulfate, a drug intended to prevent early labor, causing constant nausea and dizziness. How could I eat when the room was turning like a carousel?

Twenty-four hours later, I’m propped up against a snowy mountain of pillows with a full breakfast tray. Waffles swimming in maple syrup, a covered bowl of oatmeal, two packets of brown sugar, a plate of toast that I hadn’t even ordered…

My stomach churns in protest. The babies, butterflies waiting to emerge, flutter under my hands.

Tears hurry down my face as I contemplate the overloaded tray. Suzi, one of my nurses, sweeps into the room, smiling a good morning. “I’ve come to get your vitals,” she announces, wheeling the blood pressure cart up to my bed.

Her smile softens as her eyes read my tearstained face.

“Still feeling sick?” she asks.

I nod, embarrassed that I’m crying.

“This is too much with your stomach doing somersaults, How about a protein shake instead?” she asks.

“Yes, please..”

She grabs my hand and holds it for a moment before disappearing with the tray.

10 AM: I drink half of a vanilla protein shake. It isn’t nearly enough, but it’s a start. My laptop is open. I’m trying to write my final paper for my last Masters Class at Calvin University.

My mind wanders from my blank screen to a conversation with my lead physician, Dr. Cook, the day before.

“This is such an important week, Elizabeth. The threshold of viability. If you can press on until Friday, everything looks brighter. Your babies’ chances of survival skyrocket.”

He prays with me, and writes Romans 12:12 on a notecard. “Be joyful in hope, patient in affliction, faithful in prayer.”

Joyful. Patient. Faithful. Am I any of those?

Why am I writing about middle school theatre? Will I ever direct a play again? I’m only allowed out of bed to take a shower.

1 PM: Saltine crackers. That’s all I’ve been able to eat since the protein shake. Loneliness lingers like an old friend, My mind seems as closed as the books scattered on the end of my bed.

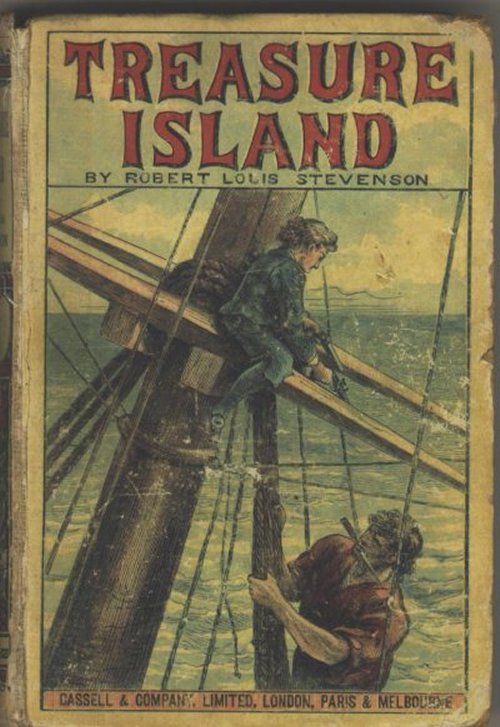

I rewrite a paragraph for the fifth time, and then, I see familiar faces in the doorway. It’s Steven, Paul, Josh, Shelley and Staci, principal cast members from the production of Peter Pan that I directed before a doctor’s orders changed everything.

“Mrs. O.! It’s so good to see you…” Steven’s words fill the semi-dark room with light, and in his voice I’m reliving scenes from the play. I hear him saying, “To die will be an awfully big adventure!” All he needs is some glitter in his hair and an epee. In my mind, he’s soaring across the stage, flying over the audience throwing pixie dust like confetti. Ageless.

“The rumor is that you need to get outside,” said Paul.

“That sounds awesome, but you would have to get me past several nurses.”

“We already have permission,” Staci insists. Shelley and Josh go into the hallway and return with a wheelchair-the chariot of 4th Floor.

Within minutes, I’m outside of my room for the first time in weeks. Steven, the Prince of the Never Land, gently pushes the chair into the elevator , while Paul and Josh complain about writing workshop without me. Piles of grammar worksheets. Homework overload.

Out in the hospital courtyard, we’re all tasting blue skies, savoring the flavor of hope.

In March, Michigan clouds rarely part, but that day, the sun glints through the trees like a cutlass. We talk about our shared memories of Peter Pan. I ask them what I could have done better. I think about how often God works through teenagers, unsung heroes that the rest of the world overlooks.

“We’ll never forget it, Mrs. O. The flying rehearsals especially,” Steven muses.

“You need to be on stage again,” I said. “You still have stories to tell.”

“When will you be back?” asks Paul. After that, no one says anything for a while, because we don’t know when that will be.

4 PM: As the sun melts lower in the sky, I know it’s time for them to go, and for me to go back. I will forever remember them as I see them that day. Beams of spring sunlight. I don’t need to tell them how much I miss them, or that I don’t want the day to end. With the unique wisdom of eighth graders, they already know.

January 2022: Unsung Heroes Still Surround Me

I remember that visit as if it just happened, because those students were unsung heroes, givers of hope and courage. So are you. You are life giving in the same way.

Thank you for being a gift.

Reading Like Writers:

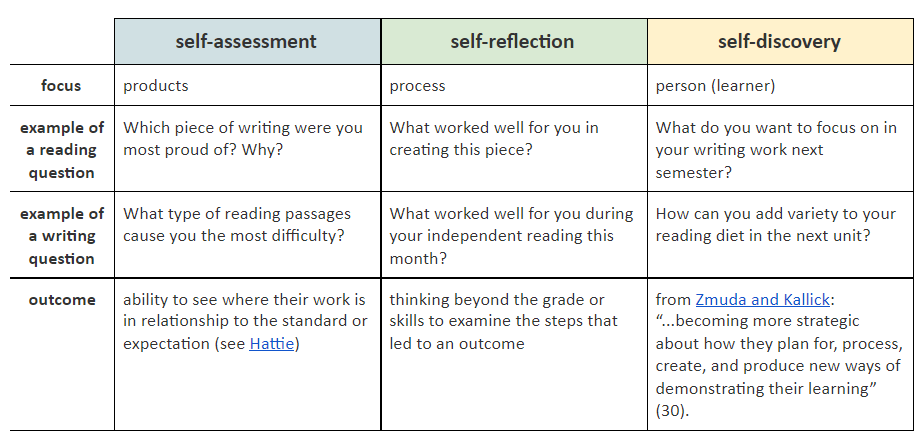

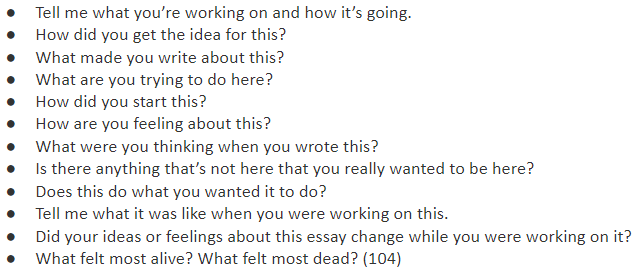

Always, I ask my students what they notice about a mentor text, whether it’s professionally written, a draft that I’m working on, or an eighth grade writer’s work. What ideas did they take away from my narrative?

- One way to write a food narrative is to approach it as a Day in the Life sort of food journal, with time stamps and short bursts of descriptive language.

- Dialogue helps to advance any piece of writing, whether it’s a food narrative or something else.

- Sometimes writers use intentional sentence fragments to emphasize words that they want their readers to notice.

- Writers may choose to use prologues or epilogues to set the stage for a composition OR to bring a piece to completion.

What Options Do Students Have During Our Food Writing Study?

Autonomy is a vital component of writing workshop, and I love to give students as many choices as possible around whatever our focal point–in this case food writing-is.

Here are a few of the options that I give them, including links to the professional mentor texts that they may explore as they think about what they would like to write, and what the best path into that writing is:

- A Food Themed Letter of Recommendation–With Thanks to The New York Times. We read this article entitled “I Recommend Eating Chips” as a way to explore excellent descriptive writing. This piece also illustrates that a good writer can write about food while at the same time cleverly expressing commentary on different cultural elements. I invited my students to write imitations of passages they admired.

- A Widow Takes the Helm at Blackberry Farm: Once again, The New York Times provided an outstanding example of a food narrative that is about SO much more than food. This is a story of tragedy, grief and resilience. The narrative is filled with beautifully structured complex sentences for students to use as mentors in their own compositions, as well as breathtaking photos of one of the most exquisite resorts in the United States.

- The Story of a Recipe: This idea came both from my own life experiences, since my great grandmother passed down incredible recipes to the next generations, and also from an NPR feature that I read about high school students sharing their recipe stories and compiling them in a cookbook. My students have the opportunity to record a recipe that they love and share why it’s important to them. The NPR feature is linked here.

We also enjoyed watching this CBS News feature about a world famous chef who is revolutionizing school lunches. Earlier this year, we wrote menus filled with our ideal entrees, beverages, sides and desserts.

Happy Martin Luther King, Jr. Day! I hope that today is a day filled with celebrations of Dr. King’s life and legacy, and of the unsung heroes in your life, including those in your classrooms.

Elizabeth Oosterheert is a middle school language and theatre arts teacher in central Iowa. Her favorite stories are The Outsiders, Peter Pan and Our Town. Recently, she wrote a script for a production of Arabian Nights. Share your amazing ideas for writing workshop in the comments below, or email Elizabeth at oosterheerte@pellachristian.net.