I already knew they were hard workers. This group of girls spent a lot of time in my classroom after school. They huddled together at the far table, speaking in a language I did not understand. They asked questions occasionally, afraid of being wrong.

“Is this right?” one would say, timidly showing me her iPad where she’d written a few sentences in the Docs app. Returning to her table, she’d share my response with her friends.

They held on in AP English by decimal points as each grading period ticked by. Lucky for them, I scored on improvement, not on the AP writing rubric.

In class we watched the documentary “A Place to Stand,” based on the book by the same name by Jimmy Santiago Baca who became a poet while serving time in prison. Baca’s story captivated my students. They identified and analyzed the argument: “Education matters. Fight for it. Words matter. Learn them. Write them. They empower you..”

Some students understood that more than others. These girls, for sure.

We read several of Baca’s poems. Although mine is primarily a non-fiction course by nature of AP Language and my syllabus, I know that it’s through poetry that my students more easily grasp the beauty and intention in an author’s craft.

The task was to re-read Baca’s poem “As Life Was Five” and to write a reflective piece in response to it.

These girls were struggling, so I finally joined them at their table.

“Tell me what’s going on,” I said.

“We just aren’t sure,” Biak said. She spoke more often than the others, although her English was only a little better.

“Can I see what you’ve written?” I asked, and she timidly passed me her writing, carefully penned on notebook paper.

She quickly broke into explanation: “I wanted to write my own poem. I don’t know how, and I don’t know…” Words tumbled out, and she lowered her head, waiting for me to read the page.

I looked, and before I could read anything, the words “Burmese!! STUPID and CRAZY!” shouted at me.

“Wait,” I said, “I thought you were from Burma.”

Five voices rose in chorus: “Yes, yes, we are from Burma, but we are not Burmese. We are Chin.”

I needed them to teach me. I’d never heard of Chin, and my knowledge of Burma was limited to the first few chapters of Saving Fish From Drowning by Amy Tan I’d tried to read and abandoned years ago.

“Will you tell me your story?” I asked, looking closely into the small faces of these beautiful young women, similar yet so different in features and personality.

Biak began to talk.

“We are from the state of Chin in Burma. The Chin are the mountain people. The Christians. The Burmese hate the Christians.”

And then they all talk and tell me their story:

They fled Burma with their families, leaving grandparents and loved ones behind. Sometimes not getting to say goodbye for fear the secret of their journey would be told. They traveled in groups, mostly at night, walking, walking, walking, they said. Often barely eating food, and even then, mostly rice balls or an egg stirred into water.

Bawi told of a Buddhist monk who acted as their guide. “He wouldn’t let us pray,” she said. “Every time we tried to pray, he would knock away our food. ‘Pray to me,’ he’d say, ‘I’m the one who gave you food, not God.’ He was so scary!”

“I lost my shoes,” Biak said, “I walked for miles and miles with no shoes, and the.. What are those things?” she turned to her friends, motioning with her hands like claws, “…those things that stuck to my feets?”

“Thorns,” they said.

“Yes, thorns stuck in my feets, but I had to walk. Walk and walk.”

“Walk quickly and don’t let go,” Kimi said.

“There was a pregnant woman with us. She could not keep up. When we reached the border of Malaysia, she could not run. I do not know what happened to her.”

“I remember we heard the POW POW POW. We had to run as fast as we can to cross the border. I was so little. My legs short. I was so scared.”

Biak begins to cry. She bows her head and covers her face with her hands, “I don’t like to think about it. I remember my grandmother’s face. We barely got to tell goodbye. She cried so much.”

I look around the table. Their eyes shine with memories.

“You all left family behind, didn’t you?”

They nod, and I see Van’s chocolate eyes pool with tears.

“Did you travel together?”

“No! But we all have same stories. All Chin students do,” Duh says.

“Wow,” I say, “Just wow.” My heart throbs in my chest, heavy with the weight of these stories. Resilience takes on new meaning.

“So you must think it’s pretty lame when your classmates whine about having to work a three hour shift and that’s the reason they cannot do their homework.”

The tension breaks, and they laugh.

“What an amazing gift you’ve given me,” I say, “You need to write your stories.”

“I wanted to write a book,” Kimi says, “but I don’t know how.”

I smile. “We can work on that.”

My heart changed after that chat with my girls from Chin. I also felt chagrin. I waited three months into the school year to extend the important invitation: “Tell me your story.”

I can come up with fourteen different reasons why. None of them matter.

Throughout the fall, I struggled with my classes because I focused on the skills needed to be successful in AP English instead of focusing on the individuals who needed to learn the skills to be successful in life. I forgot why I wanted to teach teenagers in the first place.

Perspective matters.

The most important conversation is the one that invites our students to tell us their stories.

Those young women from the state of Chin grew to trust me because I asked, and I listened. They told me later that I was the first teacher who asked them to tell me their stories — they had all attended U.S. public schools for at least four years.

I am sure other teachers assumed they knew. I thought I knew until I saw the emotion in five pairs of eyes. “We all have same stories,” Duh had said, but that is not true. They all have similar experiences. Their stories are uniquely personal, and they serve as cardinal prerequisites to the identities of each individual.

Identity matters.

How our students see themselves — as teenagers, thinkers, readers, writers, friends, students — matters, and to instruct the individual we must know what she believes about her abilities and her capabilities, both of which have been shaped in one way or another before she ever steps through our door.

Peter Johnston helped me understand the importance of identity in his book Choice Words. He reminds us, “[Children] narrate their lives, identifying themselves and the circumstances, acting and explaining events in ways they see as consistent with the person they take themselves to be” (23).

Trust and esteem are imperative to effective conferring. They are imperative to effective teaching. They are two cornerstones of conferences that allow for the relationships students need with their teachers, the relationships students need to learn.

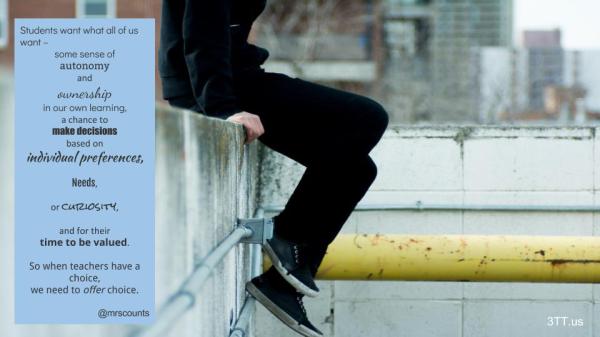

If our goal is to help our students incorporate reader and writer into their identities, we must build foundations that allow them to take on the behaviors of those who read and write. Equity and autonomy create balance in this foundation and become the other cornerstones.

All students must feel that we meet with them fairly and without judgment. They must know our goal is to inspire independence as they become more effective readers and writers — and of course, literate citizens.

Really, it all begins with the invitation: “Please, tell me your story.”

Graduates Lewisville High School Class of 2016

THAT DAY THAT DAY

by Biak Par

Far from my Home, my Family

When looking at the sky they seem so happy

But me,

Thinking about that day

Every word they speaks, every looks, every smiles, every laugh

They tear me apart, the soul sing Be Strong

That day

Every word they talk, it burn my ears like Hell

Its torture me every night, in intimidate me every day

When I see those similar faces

That day

Those word, those eyes

Tear my heart into two pieces.

Those words are as sharp as a razor

They call me foolish, Yea, I don’t know them

Burmese!

That day

My body fills with wound and remorse.

It like drawing into the water, I could not breathe nor talk,

Walking to class

All eyes on me,

Looking down with hope that there is a place I can conceal

But the room seems so small

As I take a step to the room, the room seems colder

Like I was at Antarctica,

Very Cold

Looking at the room I was isolated for this people,

This entire people are strangers.

That day

Standing still

People examine me, like I am from the others planet

That day…

My tremble body, drum in my blood

Eyes fill with water,

That day

The word of Burmese, such as STUPID, CRAZY echoed through my ears

Stupid, crazy,

My mouth wants to shout, but my mouth feels numb

And makes my throat feels tight like I am being choked,

Almost tearful

Wanting to run away can’t bear the exposes of feeling being hunted.

That day

Eyeing for a place to seat

But none of them invites me or speak,

It like I am walking into a room full of a babies Dolls,

They do not talks

But their EYES,

Their evil eyes talk, its say get out of this room

That day

Head down, looking at the floors as I walk toward to the edge of the room,

Seat alone,

The room feels so dark, so lonely and scary

Even, I was surrounding by those people

That day

My silent cry, wishing I can revisit to where I’ll be safe

Because every second, every minute, every hours this place seems so hazardous

That day…

Hopes and dreams are fading away like the wave of the cloud fade, little by little.

From that day the world is never the same

That day, change my life

Made me feels like a woman, made me realize

That because I am different from them (Burmese) and I only speak

CHIN,

They destroy and killed my hopes, my thought, my believe,

The thought of what might come next. I am Scared.

But,

My soul sing to me, be strong. BE Strong Biak Par. Be STRONG.

I’ve been asked this question in several different ways: How do we do this for college prep courses? How does workshop work in an AP English class? If I’m not teaching books from the canon, how am I preparing students for college? And we’ve written about it a lot on this blog. (See here and here and here and here and here and here for starters.)

I’ve been asked this question in several different ways: How do we do this for college prep courses? How does workshop work in an AP English class? If I’m not teaching books from the canon, how am I preparing students for college? And we’ve written about it a lot on this blog. (See here and here and here and here and here and here for starters.)