It doesn’t take much to fire me up.

Last month, I sat listening to Pernille Ripp speak at the TCTELA Conference in Galveston, TX. I’d just spent an hour walking along the beach and thinking about the presentation I would give in an hour. I’d subtitled it “Reimagining Literacy Through Secondary Readers-Writers Workshop.”

Pernille spoke as if our minds were fused. Her passion was my passion. Her beliefs were my beliefs. I haven’t read her books, but I quickly put them in my online cart.

She said some things I needed to remember to say, so I opened up my laptop and fell into an argument. A colleague had sent an email with a link to a neighboring high school’s online news article about my district’s new ELA curriculum, a curriculum that invites choice and challenge and allows teachers the freedom to plan instruction based on the individual needs of her students. It aligns with our state standards, which align with College and Career Readiness Standards. It does not require any specific texts be taught, but it does offer suggestions. Therein lies the rub.

While the student writers wrote a fine piece for high school journalists, they highlighted some erroneous conclusions about choice reading and the instructional rigor that it offers. They also seemed to side with those uninformed to the research and practical application of the workshop method of instruction. Those who just don’t get it.

I had a bit more moxie when I presented that day.

If you’ve heard me speak, or read this blog for any length of time, you know I’ve been on this journey a long while. Workshop instruction is not easy. And giving up control is only a slice of the hard part. But with talking, training, continual reading of research-based practices, and reflexive moves as a teacher, it works. It works to help students identify as readers and writers, and it works to prepare them for the work of college and the careers that will come after it.

In my presentation, I shared the why of workshop and needed more time to share the how. Later, it struck me: The how can only happen when we fully understand the why, and the why only becomes clear when we are open to understanding it.

And there are probably a lot of teachers who are working hard to make choice work who need a lot more support and training to make it as successful as they know it can be.

A few days later, my colleague forwarded me her rebuttal to the students’ news article and asked for my feedback. I did not have anything to add to her remarks. They spoke to the need of fidelity to a choice model, specifically to the advantages of independent reading, and the importance of teachers being active celebrators of books and talking to students about their reading. But I did have a few thoughts related to a lot of other things regarding the subtext of the initial attack on our new curriculum. (Of course, I did.)

On SSR and Independent Reading. There is a difference, although the two are often misused synonymously. Both prove beneficial to students readers. SSR is usually choice without parameters and little accountability, except for celebrating books and teachers conferring with students about their reading lives in an attempt to get and keep them reading. Independent reading is a much more structured approach to choice.

With independent reading, we teach using our books to study the strategies for becoming better readers and writers. We might suggest parameters like reading certain genres or books with specific themes. We might have students go into their books and find examples of characterization, how the writers move the plot forward, descriptions of setting, etc. — basically, we teach in mini-lesson format all the skills we might otherwise teach with whole class novels. Few teachers I know new to the idea of choice know this difference between SSR and the more complex approach to choice with Independent Reading. In my AP Language class, I do a combination of both.

On Research. The research is immense on the importance of experiential reading. I am sure you are familiar with Louise Rosenblatt’s work on Transactional Theory. Many other edu-researchers today build upon it, most recently Jeffrey Wilhelm, Kylene Beers, Bob Probst, and Penny Kittle. Today few high school English teachers I meet outside this blog circle understand this research. They teach the way they were taught, and many came to be English teachers because they love literature, not because they believe their job is to teach students to become readers and writers.

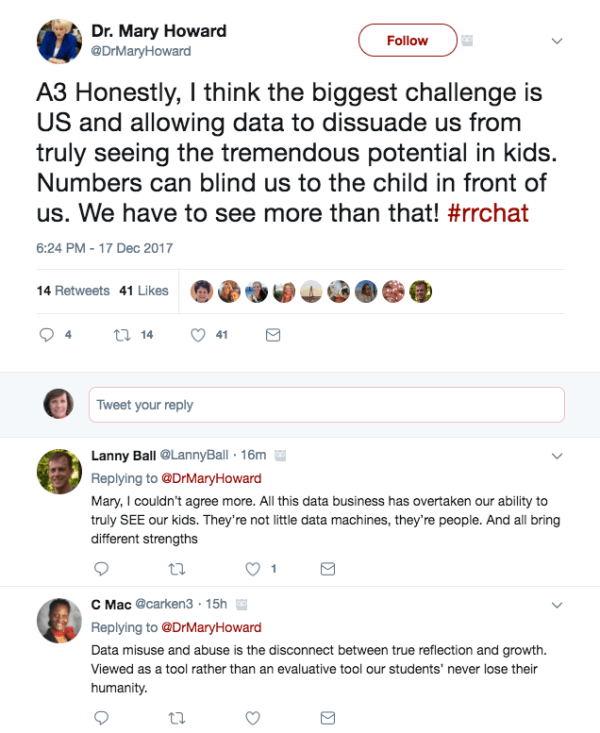

If we were to ask: What is the theory that guides your practice? They would not be able to answer. I always refer to the research of Richard Allington and often quote an article he wrote with Rachel Gabrielle, Every Child Every Day. All students need the six things they mention, yet high school teachers often discount this research claiming: That’s only for elementary. Of course, this is not true.

On Reading. Most teachers know the majority of their students do not read the required texts, and to hold students “accountable,” they give quizzes with questions “that cannot be found in Sparknotes or other online sources.” I have heard so many teachers say this! Instead of working to include students in the decisions important to their reading lives, they use punitive methods, disguised as grades, to turn students away from reading and into cheaters. Sure, there are some students who will read assigned texts, but if teachers would be vulnerable enough to actually ask their kids, so many would tell the truth: they do not read. So not only do teachers enable dishonest behavior, they do not move their students as readers.

The only way to become a reader is to read. The same holds true for writing. If teachers give students choice in topic, form, etc, students are less likely to plagiarize, especially if the writing is done in the classroom with the teacher present to confer and coach students through the writing process. Plus, most teachers who rely on the whole class novel do not have time for authentic writing instruction. It just takes too long to work through whole class novels. Students write analytical essays over books again and again — the form of writing they are least likely to write in their careers and even in college, unless they become English majors (and if you didn’t know, the numbers of English majors continues to fall.)

On Engagement. Research shows that when students are engaged, they are more apt to learn. Many teachers confuse engagement and compliance. Many young people, especially those in schools and in classes where grades are the focus, are compliant. And we’ve trained students to reach for the grade instead of diving deep into the learning. In my experience with these students, they want to know how to make the A. They take few risks, and they get frustrated when I intentionally keep things ambiguous so they have to struggle with the learning. I get quite a lot of push back, which of course, ties in to growth mindset, another area rich in research. The systems we’ve created with grades and sit-and-get education have stagnated curiosity and the drive to learn for the sake of learning.

On Rigor. As Penny Kittle said, “It’s not rigor if they are not reading it.” Somehow, and I am guilty of this in the past, we think that complex texts equate to rigorous instruction. This simply is not true. The rigor is in what we have students DO with the text. How they think. How they interact. How they work through the process of learning.

I recently read Jeff Wilhelm’s article on interpretive complexity. He states: “Interpretive complexity, or what the reader is doing with the text, should be the focus of our teaching. We don’t teach texts! We teach specific human beings—our students—to engage with texts.” For any teacher who wants the control of only “teaching” required texts, I have to ask: So how are you teaching the “specific human beings” sitting in your class? Doesn’t specific imply some level of individuality?

Most teachers I know claim to hate the system of standardized tests, yet when we make all the choices in our classrooms, we are standardizing our instruction. This reeks of hypocrisy. On the contrary, instructional methods that involve choice invite students to own their learning. We talk so much of student-centered learning, yet when we hold hard to the harness, few students ever get the chance to take the reigns. If we are confident in our content, and we identify as readers and writers ourselves, we are more able to step out of the way and facilitate deeper learning that meets the needs of each individual.

I could probably go on, but those are the main reasons my ire is up at the moment. In all honesty, I know most teachers work hard, but some just do not want to change. They want to keep doing the same thing they’ve always done because it is safer. If they stick with the classics, parents probably won’t push back, and students will go with the flow —especially if they have never experienced anything other than the way English has always been taught.

If we want to reach and teach each child sitting in our classrooms each day, isn’t it about time we take a hard look at what methods we use and ask some serious questions? Are we limiting our students’ growth or fostering more of it? Do we hang on to control or hand it to our students? Does the research support or counter our methods?

Our students deserve the best education we can give them. Why put limitations on their learning?

Amy Rasmussen teaches English IV and AP English Language and Composition at a large senior high school in North TX. She is grateful to the North Star of TX Writing Project and Penny Kittle for showing her the benefits of choice and challenge; otherwise, she would probably still be dragging students through Dickens’ novels and pulling her hair our over plagiarized essays. Thank God she learned a better way. Follow Amy @amyrass and @3TeachersTalk. And please join the Three Teachers Talk Facebook page if you haven’t already. Join the conversation and share the good news of your workshop classroom.