When I found out late last summer that I’d be returning to the classroom in person, full time for the 2020/2021 school year, I was equal parts elated and terrified. Having basically not left my house in months, I couldn’t fathom how we’d manage to move back into the classroom with any sense of normalcy or how I’d keep myself, my family, my colleagues, and my students safe simultaneously. Pandemic teaching sounded to me like a mashup of dystopian proportions.

At the same time, teaching from home all last spring brought with it challenges I didn’t relish either (My husband and seven year old daughter were home working alongside me and there were times we were each/all ready to pack a bag and go…who knows where. Mostly elsewhere). I once again considered returning to my roots as a barista or possibly trying to sleep through the coming school year. Healthy, yes?

As news trickled in about navigating our return, it was clear we were building an airplane thirty-two thousand feet off the ground. A noble effort to be sure, but harrowing, dangerous, frightening, and quite possibly deadly. As educators have been time and again, we were being shoved to the front lines. Not as well-equipped or even trained first responders, but instead, as the humble servants who apparently swore oaths to serve and protect no matter the circumstances or cost. I was to be handed a mask and optional face shield, told to keep distance from the thirty students in my room, and do the job I had signed up to do. It did not sit well.

I raged – How could they ________ ?

(Fill in the above blank with four million questions about how it would all possibly work)

I feared for my safety – If I get sick what will happen to ________?

(Fill in the above blank with anyone I love and had been working so hard to protect in the previous months by staying home, masking, not hugging my own mother, etc.)

I cried – But what if _______?

(Fill in the above blank with an equal number of less rational and more emotionally charged wonders)

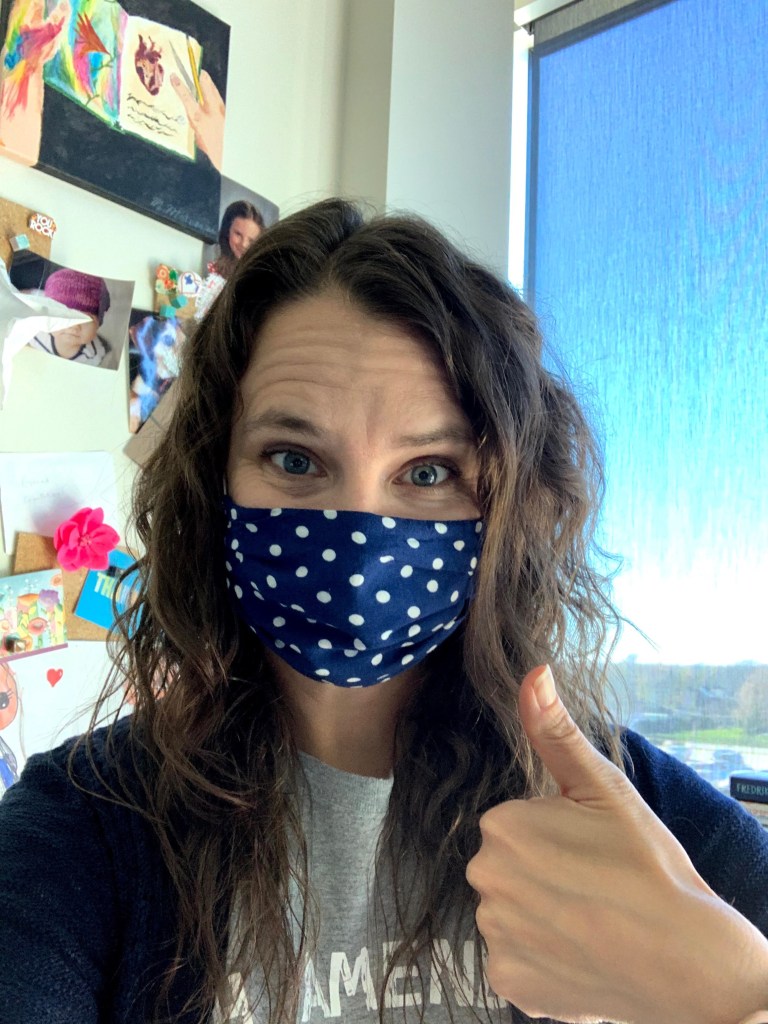

And while I’m not here to tell you it’s all gone perfectly, or that all of my initial concerns were or even could be addressed before we jumped in, or that the same will be true for you if you’ve yet to return – we have in fact done it. For eight months, I’ve taught in person and virtually at the same time (during the same class hour, in fact). 30 kids in my classroom. Masks all the day through. Suspicious eyes cast on every cough, sneeze, and inadvertently exposed nose.

We’ve shut down just once for two weeks last fall, but otherwise through a revolving door of exclusions for both students and teachers, staff turnover, extended class periods to allow time for cleaning each hour, and nervous moments spent supervising hundreds of unmasked students during lunch…we’ve supported one another through the uncertainty.

In some ways, things are no different than they ever were. My students read at the start of each period, write about what matters to them, and challenge themselves to discuss the weighty issues of our times both intelligently and diplomatically. The room looks much as it always has, but beneath the masks we wear each day, are fears and questions and uncertainties and trauma I could not have imagined last spring when I walked to my room in a haze on March 13th after a brief staff meeting suggesting our spring break would be extended by a week, gathered a few items to teach from home, and looked around at my empty classroom with a growing sense of dread.

Over a year later and as a mirror to live outside of my classroom, it all seems surreal. The longest school year of my life and the quickest. The most stressful, to be sure, but also the most challenging in ways that have caused me to grow in resilience, patience, and compassion.

A few days ago, Melissa asked if we were okay. My answer is yes, and no, and sort of, and I don’t even know. The layers of exhaustion wrought by worry, extra duties, student exclusions, positive Covid cases in my room, and teaching as I never have before (basically tethered to my desk so students at home can hear me while students in the room likely wonder whether my ankles are twisted or I’ve just grown lazy) are just too much. And yet, having kids in my classroom (and even teaching Virtual Film as Literature to 34 black Google Meet boxes), is the light in this dark time. Their curiosities and triumphs push me forward.

So, if you are staring down a return in fall, I cannot be the one to hug you (for obvious reasons) and say everything will be alright. But I can assure you through my example, that you are not alone in your fears, but likewise not alone in the overwhelming sense of joy you’ll feel by seeing your students in person and stretching in a thousand ways to inch back toward a new normal.

What I have learned in this past year (not related to making your own cleaning products, conserving toilet paper, or managing familial relations in close quarters for weeks on end) will forever change my teaching, but also solidify that nothing can shake the core principles that existed well before this pandemic …

- Students and teachers are resilient, but still human:

- If there was ever a circumstance to put patience and understanding at the forefront of our work, this pandemic is certainly a contender. It adds an ever present layer of uncertainty that is equal parts traumatic and debilitating. We’ve all experienced loss and change and fear and stress in ways we’ve collectively never experienced before. As ever, students need structure and support as they school in new and sometimes scary ways. Listen more/talk less. Write more/grade less. Read more/test less. Be there for your students, but also for yourself.

- Reading and writing offer timeless benefits we know well, but choice is more important that ever:

- I recall last spring, the push to have students write about their experiences in quarantine. And then the push back with the consideration that many students couldn’t/didn’t want to try and process this fresh trauma. It’s been my guide this year in offering students far more opportunities to process through SEL grounded prompts, but there’s always choice. Some students have written all year about the pandemic and what it’s meant to them, done to/for them, taken from them. Some students want to write about anything but. In the weeks and months ahead, our students will be on different timelines with their experiences and per the usual, it will be our job to be equal parts support system and challenger to process the world in which we live. Fall back always on choice – it provides for our students what our limiting circumstances often cannot.

- Toxic positivity is not the answer, but active engagement in seeking positivity can be:

- We cannot know how deep the cuts from our recent experiences truly are. We don’t know for ourselves or our students. Personally, the opportunity for deep and meaningful change that seems to have passed us by in hitting the pause button on traditional schooling is a deep cut. The standardized test slog is still in place (don’t get me started on the calls to measure “learning loss” with tests, tests, and more tests…though there are some reasonable voices out there), our hours/schedules/calendars are largely unchanged despite unprecedented additions of responsibilities and stress, and most importantly, to my mind, the opportunity to restructure in a meaningful way to address unconscionable achievement gaps often resulting from inequitable systems and misinformed priorities across education. This year has reminded me that I must continue to use my voice to advocate change in our work, but the moment to moment with kids demands that I give them as much positivity as I can muster. And when my store of smiles is low, I give myself the grace to take a step back, take a deep breath, and take time for myself, because in this circumstance we need to take a little to have anything left to give.

Above all, do what you need to do to balance the unending demands so that you and your family come first every single time. We are only as good for our students as we can be to ourselves, and we can be better each day when we prioritize our health, our loved ones, and our own sanity.

Lisa Dennis spends her school days teaching AP Language, English 9, and Virtual Film as Literature while also leading the fearless English Department at Franklin High School, just outside Milwaukee, Wisconsin where she lives with her husband Nick, daughter Ellie, and beagle Scout. She now tries to live life based on the last pieces of advice her dad gave her –

Be kind. Read good books. Feed the birds. Follow Lisa on Twitter @LDennibaum