Join us for a summer series revisiting our top posts from this school year, and please “turn and talk” with us in the comments section each week!

Join us for a summer series revisiting our top posts from this school year, and please “turn and talk” with us in the comments section each week!

This 2017 post by Amy Estersohn details one answer to the age-old workshop question: how to balance choice and whole-class novels.

I spent my President’s Day-Week vacation (the one that New York teachers and students get- yes, a whole week off for President’s Day!) scrapping my whole-class unit on The Outsiders and rebuilding it to reflect the values of a reader’s workshop. First, I had to define my values:

- Choice in what we read and what we read “for” (information, entertainment, character chemistry, therapy, etc.)

- Diversity in opinions, experiences, and interpretations

- Engagement in ideas. I always like to tell students that you don’t need to read to think, but a book can make you think something you haven’t thought about yet

I also had to define my teacher non-negotiables:

- Reading for ideas. Students will be able to read a scene from a book and connect it to an idea

- Tracking how that idea changes over time. Students will be able to see how ideas unfold and develop over the course of a story, either by using a chronological progression to explain how an idea unfolds (At the beginning of the story… in the middle….at the end) or a more conceptual approach (At first I thought…. Then I realized….)

Here’s how a typical lesson on a typical day looks like in this unit:

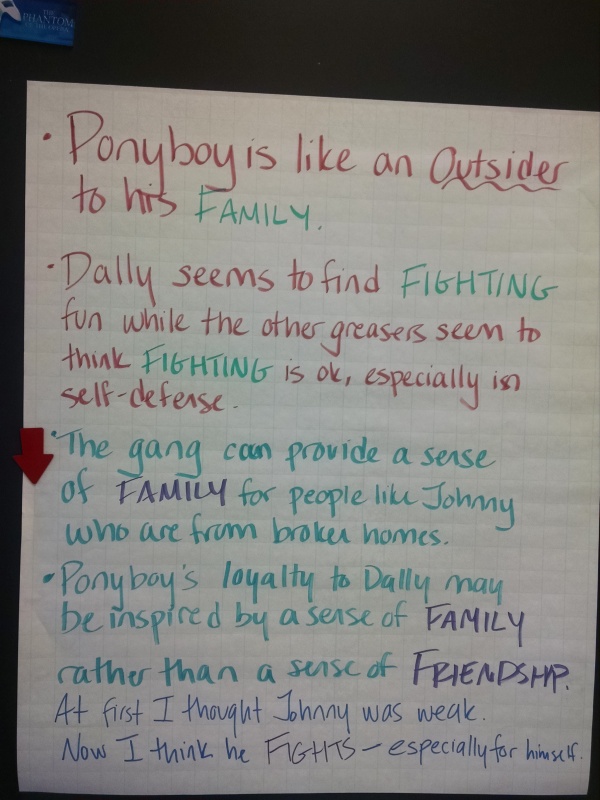

- A visual reminder of what we’re reading for when we’re reading The Outsiders

- A mini-lecture on the chapter. After I summarize the chapter, I choose a passage and my readers help me write an entry. I make sure my passages reflect “small moments” of the book instead of the plot-heavy moments of the story to show how careful reading leads to intellectual rewards.

- A group “crowdsourced” journal entry on my chosen passage. This requires a lot of fast, on-the-spot teacher thinking, as I will call on one student to begin the entry and another student to provide a follow-up sentence. I like the idea of composing a paragraph in real time under real demands, because it allows me to ask the questions that writers should be asking when they write, like “What more can I say here?” and “Do I have any evidence to explain this idea?” Later on, I post each class’s journal entry for other students to see and appreciate. I emphasize that four different classes will have four different readings of the same scene.

- Time for individual journal entries on one of our four major ideas. I invite students to post-it note possible scenes to write about as they read, through I don’t require it and I don’t encourage students to annotate as they read, either. (Incidentally, my low-stakes approach to post-its has resulted in more student requests for more post-its than I ever thought possible.) Most students have a scene or two that they want to take ownership of in their own notebooks. Some students will continue the conversation we had as a whole class in their own notebooks, taking the scene I chose and adding something new to it.

- Time to share our thinking at the end of class.

I also post and tracking some of the “greatest hits” ideas, ideas that I know will inspire strong thesis statements once readers finish the book. By the time students prepare to write an essay, they will have a menu of student-generated thesis statements along with their own thinking about the book to reflect on.

Adapting this teaching to other books.

I was thinking about how I might teach other works using the same approach. Here’s one thing I’ll say to high school teachers in particular: if you try this, you’ll find yourself making careful decisions about what you really want students to know and what you will let them figure out on their own. It means letting some “juice” of the book drop and appreciating that you won’t have time to discuss the importance of every reference with every student.

For example, if I were teaching The Great Gatsby, I think I would let readers encounter and interpret the Valley of Ashes and Dr. T.J. Eckleburg on their own. I would want to instead focus on Nick’s first description of Gatsby as a quasi-Moses figure and the fact that he dropped out of St. Olaf College — small details that lead to powerful and enduring interpretations and ideas.

Some suggested ideas and topics for popular high school books:

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

- Civilization

- Friendship

- Trust

- #ownvoices (if you aren’t familiar with this twitter hashtag, look it up!)

The Great Gatsby

- Sin and Religious Iconography

- Money

Macbeth

- Greed

- Lies/Lying

- Power

- Dreams/Reality

How are you using workshop methods and thinking to approach whole class novels?

Amy Estersohn is a middle school English teacher in New York. When she was in middle school, her favorite authors were William Shakespeare and Meg Cabot. Follow her on twitter @HMX_MSE