I am a collector. I collect bookmarks I don’t use and tweets with headlines I think I’ll read later. I collect cute little pots I think I’ll eventually make home to plants, and notebooks I’m afraid to mess up with a pen (from my pen collection, of course.)

I also collect lists. Doesn’t everyone?

I collect lists of books thinking this will keep me from buying more books. Sometimes it works. Not often.

We’ve shared several lists of books on this blog: Coach Moore’s list of books he read this summer, Shana’s Summer Reads to Stay Up Late With, Amy E’s Refresh the Recommended Reading List, and Lisa’s Going Broke List just to name a few.

I like reading lists about books. This helps me stay current on what my students might find interesting or useful. Often, I find titles that help me find the just right book for that one students who confuses “reading is boring” with “I don’t read well,” or “I don’t know what I like to read.”

With one heartbreaking event after another in our country lately, I keep thinking about the importance of reading to help our young people grow into compassionate citizens who more easily understand their world. Did you see the results of yet another study? Reading makes you feel more empathy for others, researchers discover.

Of course, we don’t need another study to tell us this. Many of us see it in our students.

I see it in my students. My students who enjoy reading also enjoy talking about their

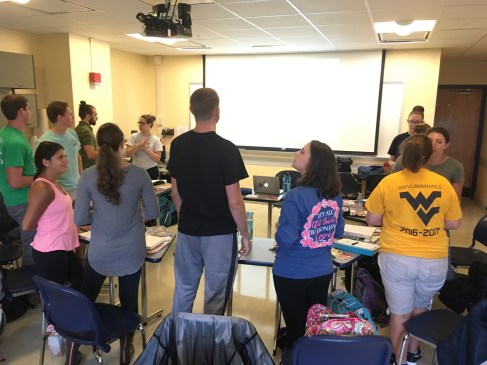

My students chose from nine different books for their book clubs. Once they chose, we had five different book clubs happening in one class. At the end of our second discussion day, I had students combine groups and talk with one another about the major themes, make connections, and share a bit about their author’s style.

reading. They relate to one another more naturally as they talk about their books, the characters, the connections. They welcome conversations that allow them to express their opinions, likes and dislikes. They learn much more than reading skills through these conversations.

My AP Language students recently finished their first book club books. I left them largely without a structured approach to talking about their reading. My only challenge on their first discussion day was to stay on topic: keep the conversation about the book for 30 minutes. They did. I wandered the room, listening in as I checked the reading progress of each student.

On the final discussion day (three total), I reviewed question types and used ideas from Margaret Lopez’ guest post Saying Something, Not Just Anything, and asked students to write two of each question types: factual, inductive, analytical prior to their book club discussions. This led to even richer conversations around their reading.

I remember reading a long while ago about how conversations about poetry could invite opportunities for solving big problems. I don’t know if this is the article I read, but the poet interviewed in this article asserts it, too:

I think we know the world needs changing. Things are going awry left and right. I firmly believe that in our very practical, technological, and scientific age, the values of all the arts, but of poetry in particular, are necessary for moving the world forward. I’m talking about things like compassion, empathy, permeability, interconnection, and the recognition of how important it is to allow uncertainty in our lives.

. . .Poetry is about the clarities that you find when you don’t simplify. They’re about complexity, nuance, subtlety. Poems also create larger fields of possibilities. The imagination is limitless, so even when a person is confronted with an unchangeable outer circumstance, one thing poems give you is there is always a changeability, a malleability, of inner circumstance. That’s the beginning of freedom.

When we invite our students to read, and then open spaces for them to talk about their

This group had hearty discussions around Hillbilly Elegy by J.D. Vance. It’s Western Days. They don’t always wear hats and plaid and boots, even in Texas.

reading, we provide the same opportunities that discussions around poetry do. Maybe not on the micro scale of ambiguity and nuance, but most certainly on the macro scale of possibilities. Our students are social creatures, and we must give them spaces to talk.

So I collect lists of books I think my students may like to read, with the hope of engaging them in conversations — with me and with one another — around books. (A couple of years ago, Shana and I had students create book lists as part of their midterm.)

Here’s five of the book lists I’ve read lately. Maybe you will find them useful as you curate your classroom libraries and work to find the right books for the right students, so they can have the conversations that help them grow in the empathy and understanding we need in our future leaders, right or left.

6 YA Books that are Great for Adults

50 Books from the Past 50 Years Everyone Should Read at Least Once

The Bluford Series — Audiobooks

20 Books for Older Teen Reluctant Readers

43 Books to Read Before They are Movies

Oh, and if you haven’t read Lisa’s 10 Things Worth Sharing Right Now post in a while, now, that’s an awesome list!!

Amy Rasmussen loves to read, watch movies with her husband, and tickle her five grandchildren. She’s in the market for a lake house and likes to shop thrift stores for books and bargain furniture. Someday she’ll be disciplined enough to write a book about teaching. For now, she teaches senior English and AP Lang and Comp at her favorite high school in North TX. Follow Amy on Twitter @amyrass, and, please, go ahead and follow this blog.

college students, and individuals in the workplace, they need to speak purposefully and ask intentional questions. I want them to be able to

college students, and individuals in the workplace, they need to speak purposefully and ask intentional questions. I want them to be able to

Right?

Right?

If we do not discuss the hard topics in our classes, where will students ever learn to discuss the hard topics? Sure, we can hope they debate social, economic, and political issues in their homes, but we know many families do not have meals together much less conversations. And it’s the conversations, varied and diverse, that can help us view the world in a different light — sometimes a cleaner, clearer, more empathetic and compassionate light. I think we need more of this light.

If we do not discuss the hard topics in our classes, where will students ever learn to discuss the hard topics? Sure, we can hope they debate social, economic, and political issues in their homes, but we know many families do not have meals together much less conversations. And it’s the conversations, varied and diverse, that can help us view the world in a different light — sometimes a cleaner, clearer, more empathetic and compassionate light. I think we need more of this light. Today is a day worth talking about.

Today is a day worth talking about.

I’ve been thinking carefully about

I’ve been thinking carefully about

Far too much of the reading, writing, speaking, and listening that our students do is for the purpose of extraction, and not interaction. Of course it is–what can be extracted is easier to measure than what can be inferred, experienced, or connected with. We’ve taught students to read in order to answer a question; to listen in order to reply.

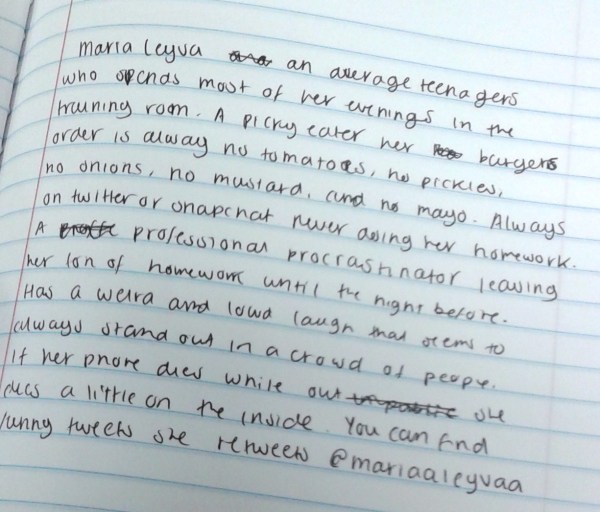

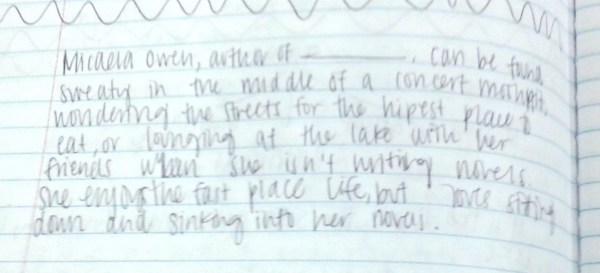

Far too much of the reading, writing, speaking, and listening that our students do is for the purpose of extraction, and not interaction. Of course it is–what can be extracted is easier to measure than what can be inferred, experienced, or connected with. We’ve taught students to read in order to answer a question; to listen in order to reply. I prepared first by reading the inside back covers of some of my hardback YA literature. I chose four bios with similar elements: Andrew Smith,

I prepared first by reading the inside back covers of some of my hardback YA literature. I chose four bios with similar elements: Andrew Smith,

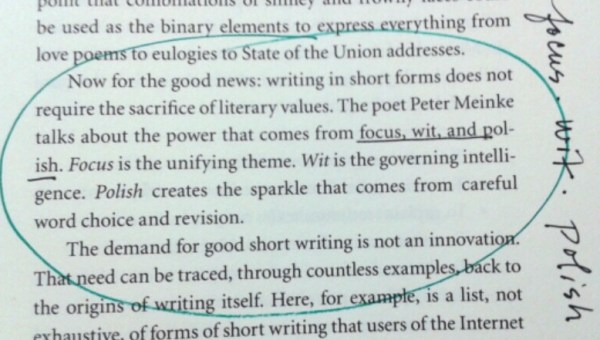

I reminded students as they write over the next few days — finishing their multi-genre projects, their last major grade — to write with intention, to write in a way that shows the answer to the last question I’ll write on the board this year: How have you grown as a reader and a writer?

I reminded students as they write over the next few days — finishing their multi-genre projects, their last major grade — to write with intention, to write in a way that shows the answer to the last question I’ll write on the board this year: How have you grown as a reader and a writer? I like to organize my thoughts this way. And, in no way am I suggesting that pulling ideas from a text is malpractice. At the end of the day, of course we need students to think deeply about their reading and demonstrate that thought through talk, written reflection, and/or analysis of some kind.

I like to organize my thoughts this way. And, in no way am I suggesting that pulling ideas from a text is malpractice. At the end of the day, of course we need students to think deeply about their reading and demonstrate that thought through talk, written reflection, and/or analysis of some kind.

of the class period, we used our essential question (What is the individual’s responsibility to the community?) to guide a discussion. I used PowerPoint slides to project a symbol and that group went to the front of the room to start talking. Other groups made notes on where they would take the conversation when they were called into the discussion.

of the class period, we used our essential question (What is the individual’s responsibility to the community?) to guide a discussion. I used PowerPoint slides to project a symbol and that group went to the front of the room to start talking. Other groups made notes on where they would take the conversation when they were called into the discussion.