I am committed and inspired to move into true Reader’s Writer’s Workshop after NCTE and a near semester under my belt in a new school. I left for the conference in Houston with a plan to read The Great Gatsby in December, and as much as I wanted to totally scrap it and start with a routine inspired by Penny Kittle and Kelly Gallagher in 180 Days, I didn’t.

I paused.

Although every classroom minute is precious and developing readers is the most timely need, I wanted to give myself time to process this shift, to think through how my classroom would run, and brainstorm how to help my students, who from my inquiries have only experienced the full class novel, navigate texts with more autonomy and independence.

Going from trained text regurgitation to full choice would have been a huge, potentially disastrous, shift for my students. Since August, they have looked to me to create meaning, to judge whether their writing is “right” or “good,” asking what I think about the text versus presenting their own original idea. These students will grow immensely from workshop, which makes me so excited for January, but I felt they first need scaffolding up to meaning-making and trusting their interpretation and ideas.

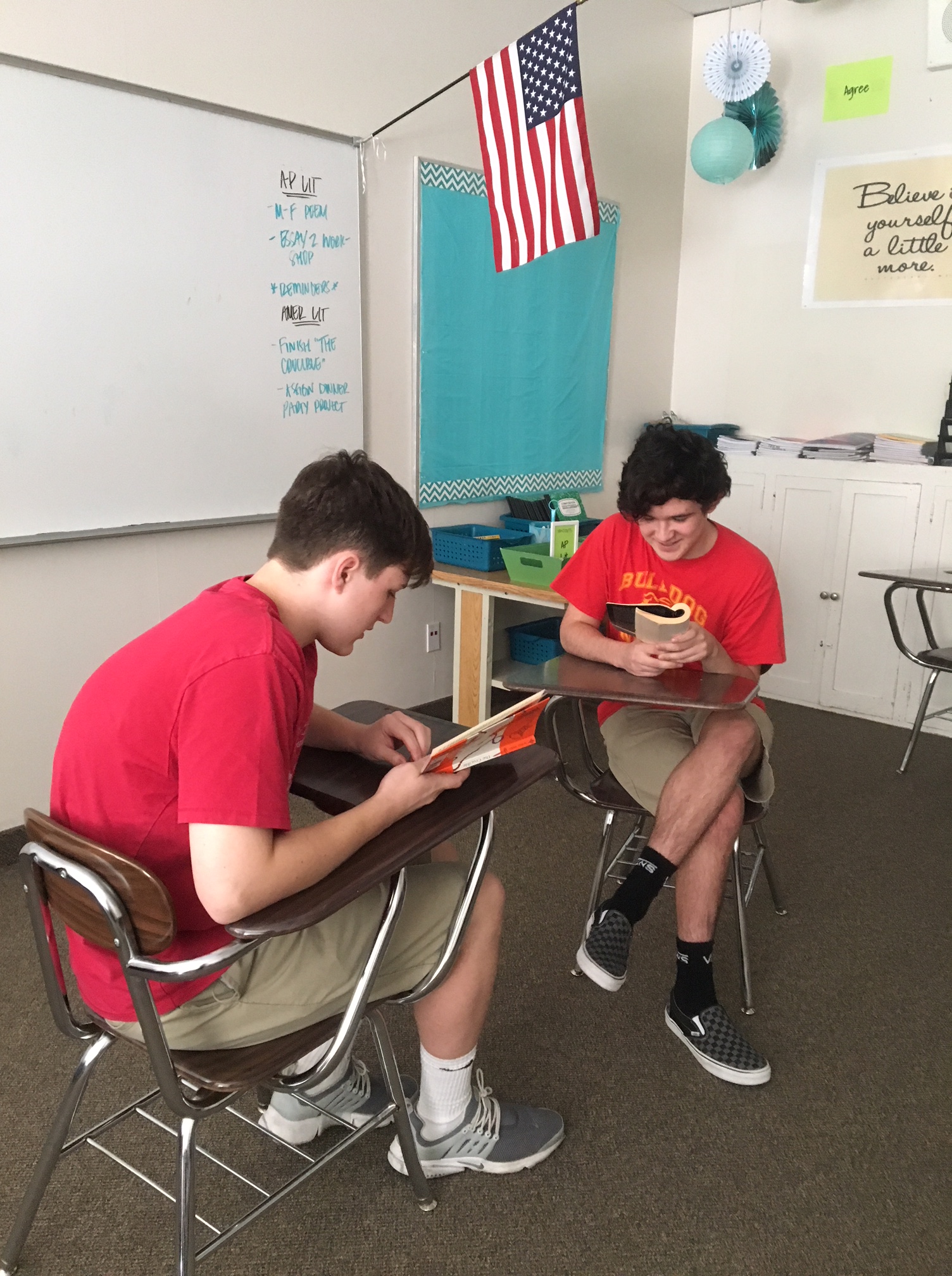

I created a Book Club atmosphere with students for our reading of The Great Gatsby, having students meet in “Discussion Tables” with their peers to process the text with each other. As 180 Days suggests, I asked students to come with one question and one comment to their discussion tables. Students were also responsible for close reading and annotating/sketchnoting key scenes of the text, commenting on development and language. Their annotations served as a launch point for continuing and deepening the conversation. A Book Club-style approach allowed for a more structured release of responsibility to students while maintaining the shared experience of full class novels my students are accustomed to. I stood back as an observer, listening in to their conversations, witnessing students make meaning together versus wait to be guided to a single answer or idea.

As the unit was primarily based on discussion and conversation, so was their culminating assessment, the “Persona Discussion.” Students were given a choice of what character they wanted to embody, from the core characters like Jay Gatsby and Daisy Buchanan to more minor characters like Mr. Gatz or Meyer Wolfsheim, even “background” characters like the party goers were an option for students. The core characters provided limited space for interpretation while added characters, like party goers, allowed for more creativity in the persona. Students signed up for a character and prepared by thinking through their characters in their journals.

The discussion works like a Socratic Seminar, where students are the drivers of the discussion and can be adapted for both fiction and nonfiction. I created this assignment for AP Language students who loved to debate and discuss in Chicago–they adopted the persona of Henrietta Lacks’ family, doctors, and author Rebecca Skloot after reading The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks. For Henrietta’s Persona Discussion, the central question of the discussion was a quote about medical ethics.

Students felt that the smaller characters were given a voice, an idea we discussed earlier in the passage when examining the wealth and marginalization of “the other” characters in efforts to disrupt the traditional text.

Maggie, who played Myrtle, said she liked feeling immersed in the book: “At first, I felt like Myrtle would only ask questions to Tom or George, but as we all started being our characters, I thought about how Myrtle and Gatsby were actually more alike and could have been friends, and I wanted to ask Daisy about her marriage more.” Jordyn said the discussion was better for understanding the web of deception because “…it was like seeing the book as a play or real life and it made our group discussions more real or, like, meaningful.” After discussing the text as a reader so much, Riley, a reluctant reader who has learned, as he admitted, to “fake it,” said, “It was more fun to prepare to play someone than to think about the big ideas for a regular seminar. It made me want to do well and really know Tom.”

As we build into full workshop mode in January, students have a foundation for how to enter a text, methods for creating meaning, and more confidence in their thinking. Students were engaged with this type of discussion and reflected about their enjoyment, so I am going to incorporate it into next semester, perhaps jigsawing the characters from students’ choice reading or book clubs together from different realms or as a way to review major characters and texts before the AP Literature exam. We’ll see what other “personas” develop!

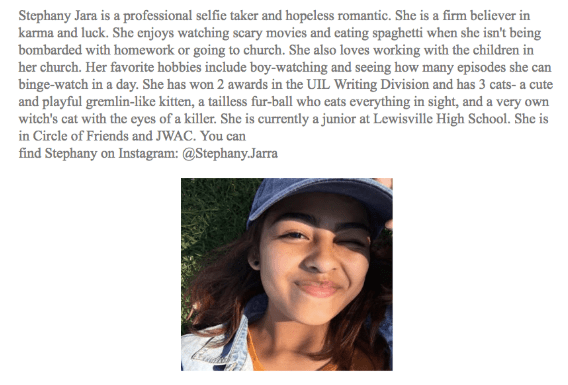

Maggie Lopez is enjoying Utah ski season while re-reading 180 Days as she preps for second semester, American Girls: The Secret Life of American Teenagers before bed, and The Poet X in class. She wishes you a very merry, restful holiday season!

I love going back to school for so many reasons, but one of the frontrunners is definitely that “second chance new year” feeling it provides. Teachers and students have the unique opportunity to have not just one fresh start at the beginning of a calendar year, but a second shot at goal-setting, changes, and achievements that the fall offers.

I love going back to school for so many reasons, but one of the frontrunners is definitely that “second chance new year” feeling it provides. Teachers and students have the unique opportunity to have not just one fresh start at the beginning of a calendar year, but a second shot at goal-setting, changes, and achievements that the fall offers.

work (heels, flats, boots, hand-painted Tom’s with Shakespeare’s quotes…) which means I’ve spent a lot of time perusing, purchasing, and inevitably returning some of those online shoe purchases. Hands down, their company is one of the easiest to return or exchange those shoes that don’t quite match that new blazer, I also bought online. All that aside, that isn’t why I want my classroom to run like their company.

work (heels, flats, boots, hand-painted Tom’s with Shakespeare’s quotes…) which means I’ve spent a lot of time perusing, purchasing, and inevitably returning some of those online shoe purchases. Hands down, their company is one of the easiest to return or exchange those shoes that don’t quite match that new blazer, I also bought online. All that aside, that isn’t why I want my classroom to run like their company. We start the trimester by exploring Pink’s research using excerpts from

We start the trimester by exploring Pink’s research using excerpts from