I am as guilty as the next guy. When I first started teaching, I didn’t have any idea how to get students to read more, write more, do more in my English class. I didn’t even know I would have to work so hard. Although I was in the middle of raising my own teenagers (and they all turned out great), I had no idea how to inspire other people’s teens to give books a long enough look to want to read them or to take the time needed to write something they would want others to want to read. I was all about my content, my lesson plans, my choices, my control. I did most of the talking. I did very little listening.

I remember the first day of my first year teaching. Students sat in assigned seats, alphabetically by last name. I asked each student, seat by seat, row by row, to tell everyone their name and one thing they hoped to learn in their freshman English class. I have no idea what they said — except for one.

“My name is Susie, and I hate white people.”

I am a white woman.

I might have felt stunned, hurt, appalled. I do remember thinking, “The audacity!” and shouldering an internal huff. I tried not to let these words sink me before I ever got afloat, and for the most part, I think I succeeded. Susie and I learned to work together that year, and she did fine in my class.

But my idea of success is much different than it was back then: I no longer think fine is ever good enough.

I think about those young people from my first few years of teaching, and if time machines were a real thing, I’d set the dial to 2008. I would do things differently because I am different. I know better. I learned to be better.

Last week I facilitated a day-long training on implementing the routines of readers-writers workshop in secondary classrooms — a shift in pedagogy so students sit at the center and learn through authentic reading and writing practices. These teachers are eager, and their district leadership is providing support to make this happen. Yet they struggle.

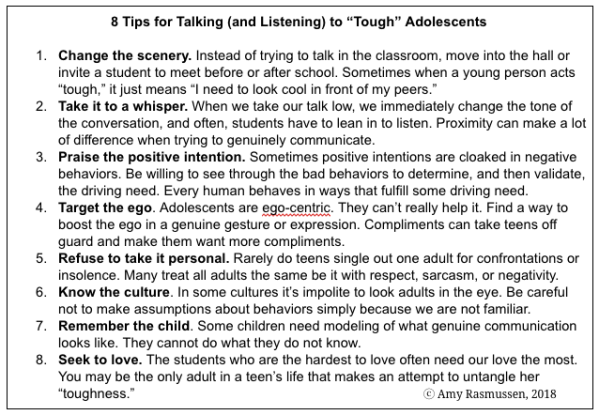

In table-group conversations, two topics came up again and again: Our students lack discipline. We need more tips on conferring.

What’s obvious to me now, that wasn’t back when I first started teaching, is a clear connection between the two. Students need to be heard. Now, I am not saying that implementing a workshop pedagogy will fix all disruptive behaviors, but I do believe these behaviors are often evidence of a lack of conferring. Students need to be seen and heard. (See more on why here.)

We talk a lot about creating a positive culture in schools and cultivating learning communities where relationships thrive. These take intention, effort, and time. In ELAR classes, these take intentionally designing instruction that utilizes every square meter as we practice authentic literacy skills with authentic texts and model the effort it takes to build our identities as readers and writers. To do all of this well, we must meet our students where they are in their learning, or in their apathy, or their attitudes, or whatever we want to call it. Conferring, those one-on-one little talks with kids, is where we do it.

As with anything that deals with humans, it has to start with listening. Listening jumpstarts relationships. Relationships build community. Community shapes culture.

If I could relive day one of my first year teaching and my interaction with Susie, I’d make sure she knew I heard her. I’d pull up a chair at the beginning of our next class, and I’d listen. That would be the start of Susie doing more than just fine in her freshman English class. I am pretty sure of it.

Amy Rasmussen loves her life in North TX. She’s currently reading We Got This by Cornelius Minor, Embarrassment by Thomas Newkirk, and Braving the Wilderness by Brene Brown. She may be a completely different person come 2019. Find her on Twitter @amyrass

away books. We presented at the Coalition of Reading and English Supervisors of Texas (CREST) fall conference, and

away books. We presented at the Coalition of Reading and English Supervisors of Texas (CREST) fall conference, and

It’s amazing that a place of scenic tranquility and beauty could rouse such feelings of rebellion and determination.

It’s amazing that a place of scenic tranquility and beauty could rouse such feelings of rebellion and determination.