Conferring is hard brain work. When do I listen? How do I listen? When do I talk? How much? How do I anticipate what a student needs? When do I step back and let them problem solve? Am I even conferring right? (Maybe not. So put your Judge-y McJudgers pants away while you read this.). As Shana explained in this post back in January, there’s so much value in talk, in engaging our students in conversation, in encouraging them–as Amy framed here— to tell the story of how their writing is going.

Because (as Tom Newkirk suggests) we have minds made for stories, over the years I’ve begun to recognize some common schemes while conferring. Recognizing these patterns frees me to listen and to respond. Perhaps you’ll recognize the stories of your own students in the stories I share. Perhaps you’ll pick up a strategy or two.

The What-Did-I-Do-to-Myself Conference

This conference may typically begin from a position of fear–mine because my student’s eyes have suddenly become two daggers, piercing my helpful, loving heart. This occurred in a recent conference, where my student who chose ice cream as her multi genre research project topic hurled at me these words: “I don’t know how I’m supposed to write an argument about ice cream.” Was she complaining about lack of direction? Instruction? I took a deep breath to let go of any defensiveness I felt. Then I reflected on her question. Oh. Oh! The fear was not mine to have.

My student needed:

- to hear that to write about this is, indeed, possible.

- to understand the possibilities for executing the writing.

Conference next steps:

- I confirmed the correctness of my reflection by paraphrasing (So, what I think you’re saying is that you’re feeling pretty uncertain if you can, and if you can, what it looks like?).

- Once confirmed, I chose another seemingly tiny and narrow topic like tacos and verbally processed some options for how I could craft an argument for an audience on tacos. I did not do any written modeling or reach for any mentors at this point. My role in this early phase conference was to dispel fear, to affirm possibility, and to confirm faith in my student’s ability.

Student next steps:

Following this verbal modeling, my student disarmed with affirmation and a smile, she continued working in her notebook, mapping her argument and the rest of the multi genre.

The I-Need-to-Change-My-Topic Conference

This conference may typically begin from a declarative statement: “Just so you know, I’m changing my topic.” I’m being put on notice here. But I delight in these William Carlos Williams “this is just to say” moments almost as much as ripe-n-ready plums. So, curious now, I say, “Tell me about why you abandoned the old topic” (I’m always thinking we can learn something from discarding topics) and “Tell me about the new topic.” That’s when my student in this case explains that the topic is music but that’s all he has. Hmm.

My student needed:

- To narrow his topic by sinking his teeth into the best tidbits of it.

- To get moving. And fast.

Conference next steps:

- With the topic so broad, I asked the student to tell me a story that shows his relationship with music.

- Once the student shared his story–one that involved him writing his own music and performing several songs at a local concert venue (Our students do amazing things!)–we mapped out a plan for the different parts of his multi genre text.

Student next steps:

With a story in his head (and probably a song) and a general plan mapped out, this student left for the day, ready to focus on more specific planning.

The So-Can-I? Conference

This conference may typically begin and end within a very short burst of time; a meteor shower during the Perseids, this conference starts with a short burst of light from the student, a recognition of how to apply a resource. In a recent case, the student examined a resource on possible argument structures I shared with the class, and ingenuity bursting forth, queried, “So, I can use the pro/con structure? And, can I make this modification to it?”

My student needed:

- To know that he has more freedom than he’s using.

- To have the affirmation necessary to keep burning bright.

Conference next steps:

- I replied,” Tell me a little more about that” and followed that with paraphrasing, “So, what you want to do is . . .?”

- Then I simply said, “Yes.”

Student next steps:

Following this all-of-sixty-seconds-conference, the student returned to mapping out writing, synthesizing his own ideas with the resource. And, I spent five minutes with the next person instead of three.

The I-Know-I-Need-to ______ , But . . . Conference

This conference may typically begin with candor from the student. Like the first sip of lemonade on a hot summer’s day, it’s so refreshing to hear in response to my opening questions (How’s the writing going? What roadblocks are you running into?), “I know I need to _______, but I’m having a little trouble.” Ah. This can become an opportunity to model for the student or offer a micro-lesson; sometimes–like in a recent conference where my student wanted to build a more humorous tone–I help the student find or use mentors. **Note to self–I should probably start asking my students to tell me about mentor texts they’ve turned to when they’re tackling challenges.

My student needed:

- To resolve gaps in skill level (impressively, one’s the student recognized).

- To access additional resources for strategies.

Conference next steps:

- For this student working on narrative writing, I pulled David Sedaris’ “Let It Snow” and a couple of others.

- Then we talked through typical strategies a writer uses to develop humor.

Student next steps:

Time well-spent, smiling now, my student worked on reading and studying the mentors.

The I’m-Avoiding-Letting-You-Read-My-Writing Conference. May also sometimes appear as the I-Don’t Have-Any-Writing-to-Show-You-Yet Conference

This conference may typically begin, well, haltingly–like a first time driver slowly circling around the empty high school parking lot. I’ll ask, “How is the writing going? What roadblocks are you hitting?” “Doin’ fine. No roadblocks.” Okay. Next approach. “Why don’t we look at a section together? Show me a section you feel really good about. Let’s celebrate what’s working!” Sometimes that gets us turned in the right direction (a smile and an oh, sure and we’re underway); sometimes we skid (uh, so, um, I don’t really have much yet. Uh-oh.). When I most recently tried this approach, my student offered, “Well, I really like this paragraph; but I’m not sure about how to develop it more.”

My student needed:

- to feel safe enough–safe enough to embrace the opportunity or safe enough to admit to lack of progress.

- to have re-direction for what conferring might look and sound like. Sometimes they just don’t have the mechanisms down.

Conference next steps:

- In the first situation, I generally point out the parts that are really working in the section the student chose to share. I thank them. Then I ask if there’s anything else they want to share or questions they have. And, sometimes I get to look at more writing. I did in this particular case. And, had I not pressed gently, I don’t think I would have (I was kind of impressed that it actually worked!).

- In the second situation, I paraphrase what they might be feeling. I might say, “I imagine you might be feeling ___________ (stressed for not having more done; frustrated by how to begin; confused about the direction of your writing; etc.). They typically correct me if I’m wrong and we work together to plan next steps, even if it’s breaking down the process further.

Student next steps:

In the first situation, the student began applying feedback; in situation two, the student typically articulates what’s getting in the way and what resources are needed and then begins tackling a small goal (drafting a paragraph versus drafting the whole thing).

When I’m conferring, I’m listening, paraphrasing, questioning, re-teaching, modeling, affirming, finding resources, building possibility, and showing my students that what they write matters. No wonder my brain hurts.

Kristin Jeschke remembers with fondness the many teachers that encouraged her writing but especially Greg Leitner who always listened more than talked. And who always inspired her to keep writing. Now as an AP Language and Composition teacher and senior English teacher, Kristin appreciates the gift of moments spent conferring. Follow Kristin on Twitter @kajeschke.

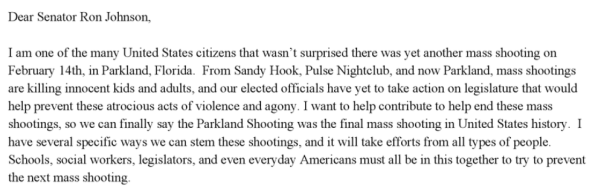

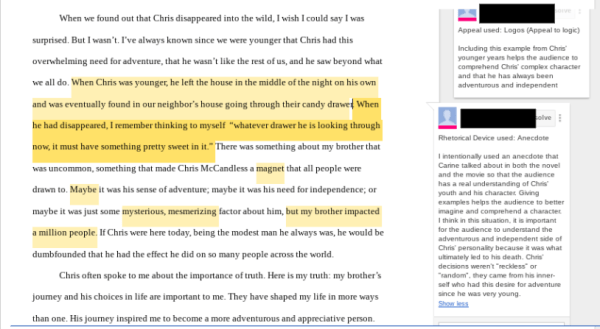

We were clear with students from the very beginning that this was not an assignment in support of any particular political agenda. Instead, it was an exercise in better understanding our preconceived ideas and more deeply, and diplomatically, developing our rationale for how to bring about change As long as their research came from credible sources, students could argue for changes to gun laws, support of the 2nd amendment, mental health considerations, school security, or any other defensible position to end mass gun violence. They could write to state or local representatives, as long as they researched that representatives current position on related issues, providing students with key insights to audience consideration we’ve previously only talked about or tried to emulate through blogging.

We were clear with students from the very beginning that this was not an assignment in support of any particular political agenda. Instead, it was an exercise in better understanding our preconceived ideas and more deeply, and diplomatically, developing our rationale for how to bring about change As long as their research came from credible sources, students could argue for changes to gun laws, support of the 2nd amendment, mental health considerations, school security, or any other defensible position to end mass gun violence. They could write to state or local representatives, as long as they researched that representatives current position on related issues, providing students with key insights to audience consideration we’ve previously only talked about or tried to emulate through blogging.