Before I became a teacher, I was a district manager for a women’s retail chain. One year the company went through a major change in their customer service program that included hours of new training. Our management team was under enormous pressure to perform, and no one was happy about the change. Marilou, our human resource manager, told us, “The only people who like to be changed are babies.” That quote has stuck with me all these years.

Before I became a teacher, I was a district manager for a women’s retail chain. One year the company went through a major change in their customer service program that included hours of new training. Our management team was under enormous pressure to perform, and no one was happy about the change. Marilou, our human resource manager, told us, “The only people who like to be changed are babies.” That quote has stuck with me all these years.

As a teacher, I have gone through so many changes. From grade levels to buildings and administrators to teaching partners and new standards to new testing and to the next how-to-get-higher-test-scores program. These changes add additional stress to already stressed-out teachers.

Change is simply a part of education; however, being changed is more accepted by reflective teachers. As I look back at the changes I have made in my classroom, implementing reading and writing workshop has been my most challenging, yet also the most rewarding.

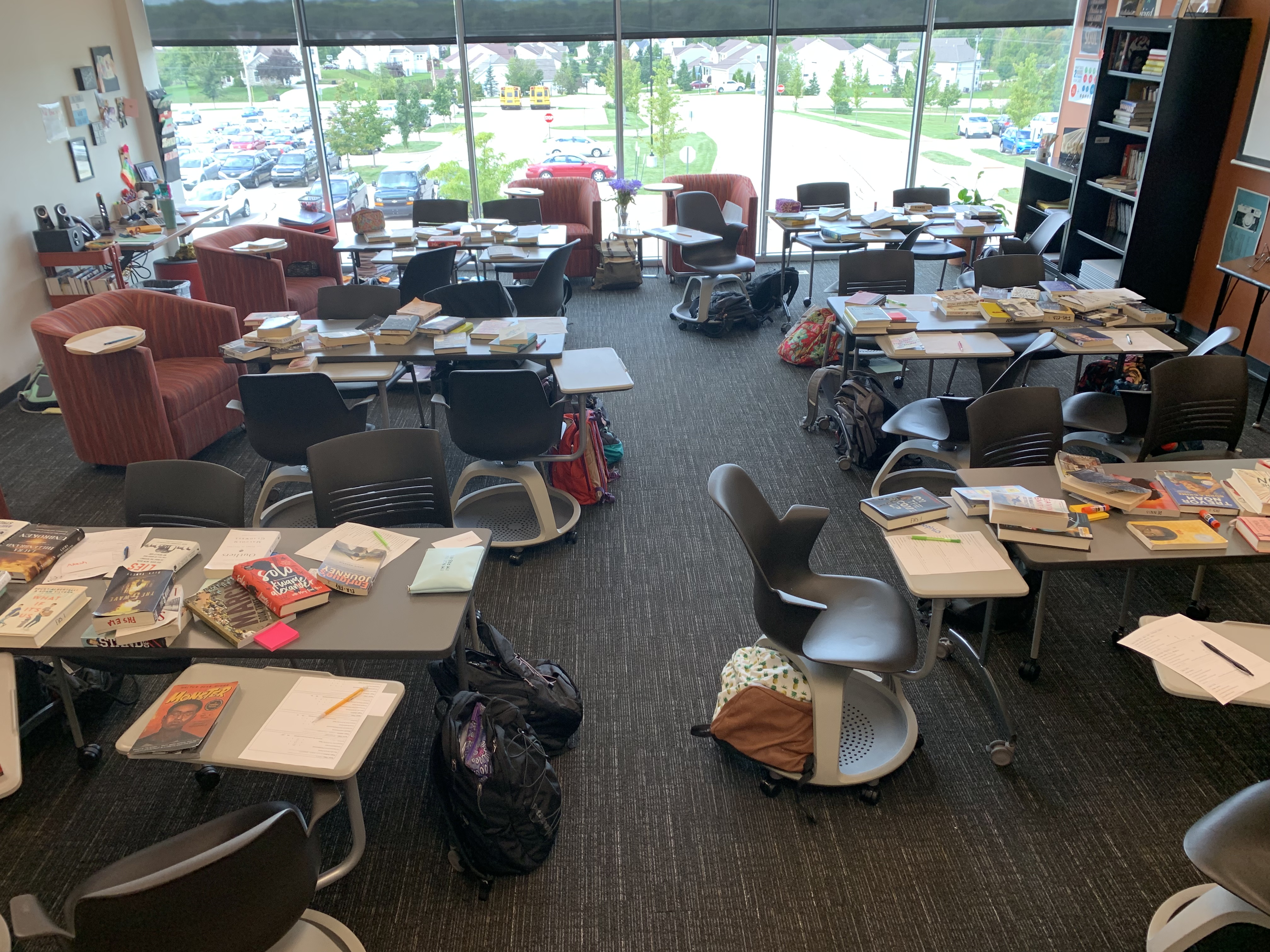

In the early stages of this journey, I read books and blogs and attended conference sessions on reading and writing workshop. I met educators on social media who have been using workshop successfully for years. They made it appear so easy. In their perfect (in my mind) classrooms, independent reading was at the forefront, writing mini-lessons moved seamlessly into work time, and conferring with students was productive. I thought this was how teaching was supposed to look and was how I wanted my classroom to be.

I started my teaching career as an elementary “basal teacher” because that was what I knew and was how the other teachers taught. Prompt writing was our curriculum because that was how writing was tested. After moving to middle school and becoming a mentor teacher, I knew this would be the perfect time to make a change toward the workshop approach.

Independent reading has been the heartbeat of my classroom for many years and was already in place. Once I made the commitment to try the workshop approach, my mini-lessons became focused on the skills and strategies my students needed to become successful readers and writers. Conferring became routine, and reading and writing became engaging and authentic for my students. None of these changes happened overnight, and I am still changing.

If you have decided to make the change to workshop, then I encourage you to think about these three ideas to get you started:

- Think Big–Start Small When deciding to implement reading and writing workshop, see the big picture. Have a goal of where you want to be but begin with little steps to get there. Implement small pieces of the workshop model. I began with choice–giving students choice in the topics to write about and the books to read. I slowly began creating mini-units that included a series of mini-lessons with work time and conferences built in. You could begin here, or you might begin with collecting mentor texts or focusing on making your mini-lessons “mini.” The important part is that you take that first small step.

- Allow Failure and Accept Grace Many days I wanted to quit and go back to what was easy. I wanted my workshop to look, sound, and feel perfect. Most days it wasn’t. But then I realized I needed to give myself some grace because change takes time. My students were beginning to see the connection between reading and writing and that the work was authentic. It was what real readers and writers do. I knew I was going in the right direction.

- Make Connections I come from a district that does not use workshop, so any learning has always been on my own. Making connections with mentors made it easier. Three resources that I read at the beginning of my journey were Donalyn Miller’s The Book Whisperer and Book Love and Write Beside Them by Penny Kittle. These three books gave me the courage to do what I knew in my teacher’s heart was right, and I never turned back.

The Three Teachers Talk blog has a wealth of resources on implementing reading and writing workshop. Penny and Donalyn were the “big picture” and Three Teachers Talk has been the “small steps” I needed for my own professional development.

My journey is far from over as I continue to learn, reflect, and change every day. I am no expert, but I share with you what I have learned in hopes to make your journey to workshop teaching a little bit easier.

I think I may need to revise Marilou’s quote to: “The only people who like to be changed are babies and reflective teachers.”

Change is hard; being changed is amazing.

As teachers, we are all on a journey, but we don’t have to go it alone. Please share your journey with us in the comments section.

Leigh Anne Eck teaches 6th grade English language arts in Southern Indiana and loves to learn. She recently recieved her Master’s degree in Curriculum and Instruction at the young age of 55. She loves partnering with her husband in parenting their young adult children. Connect with Leigh Anne on Twitter @teachr4.

Taking one paragraph each from the sample essays, we read them like writers and explored the decisions and moves made by those writers. Our process of discovery put the cognitive load on the students and allowed me to serve as a “tour guide.” We learned how our argument skills can be applied to this specific writing task, finding new words to add to our personal dictionaries and use in our own writing. We debated the use of claim and evidence and the utility of being intentional with the length of the direct evidence we blend into our argument. We examined the sentence structure decisions made by the writers and noticed how combining sentences can make our writing, and our argument, clearer.

Taking one paragraph each from the sample essays, we read them like writers and explored the decisions and moves made by those writers. Our process of discovery put the cognitive load on the students and allowed me to serve as a “tour guide.” We learned how our argument skills can be applied to this specific writing task, finding new words to add to our personal dictionaries and use in our own writing. We debated the use of claim and evidence and the utility of being intentional with the length of the direct evidence we blend into our argument. We examined the sentence structure decisions made by the writers and noticed how combining sentences can make our writing, and our argument, clearer. written or co-written over 15 books and a ridiculous number of articles for professional journals, has been honored with numerous awards, and currently holds the title of Distinguished Research Professor of English Education.

written or co-written over 15 books and a ridiculous number of articles for professional journals, has been honored with numerous awards, and currently holds the title of Distinguished Research Professor of English Education. Lately, I’ve been listening for what surprises me. What did I just hear that startled me? This isn’t easy-I’m accustomed to sitting there nodding my head to those saying things I agree with. But when I notice what surprises me, I’m able to see my own views more clearly, including my beliefs and assumptions.

Lately, I’ve been listening for what surprises me. What did I just hear that startled me? This isn’t easy-I’m accustomed to sitting there nodding my head to those saying things I agree with. But when I notice what surprises me, I’m able to see my own views more clearly, including my beliefs and assumptions. thinking and truly listen to one another, our society, and our country, have a chance. The bellowing from every side wears me down, and I think the classroom can be a tiny little microcosm of what communication in the world could be if we were all a little more well-versed in listening and speaking skills. Call me hopeful.

thinking and truly listen to one another, our society, and our country, have a chance. The bellowing from every side wears me down, and I think the classroom can be a tiny little microcosm of what communication in the world could be if we were all a little more well-versed in listening and speaking skills. Call me hopeful.