Prior to starting a round of Book Clubs with my AP Lit students, I questioned what would be a “just right” accountability fit for my very different first and fourth periods. Third quarter always hits juniors hard. It is a reality check that changes are ahead. It seems to be the time students are in full swing with clubs, theater, sports, and other projects. My students are invested in their independent reading, with many switching between texts they can use on the exam and fun YA selections, and developing reading identities. My students are also chatty and friendly–Book Clubs seemed like a perfect fit at this point in the year.

But how to keep students accountable in a non-punitive way when they’re already overbooked. I thought about my goals for the Book Clubs, which extended far beyond adding another text of literary merit to their tool belts for question three. I wanted them to read, to engage, to think. For students to have fun meeting together to discuss books like adult readers do.

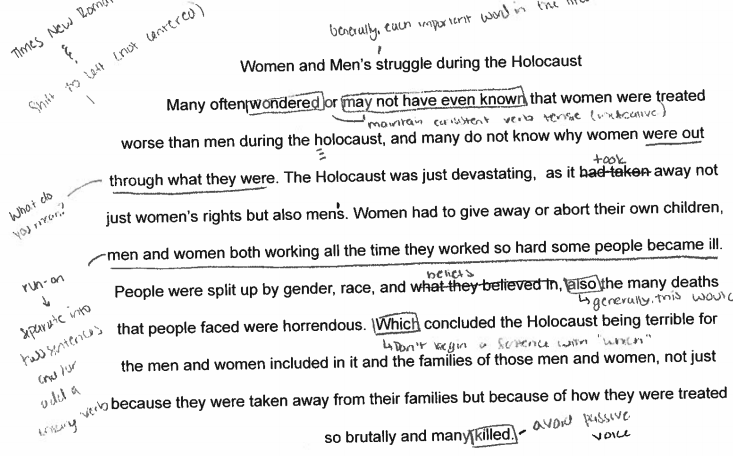

For some, a bit of accountability helps spur their reading and processing. I have many students who like to document their thinking with annotations or dialectical journals and be rewarded for their visual thinking. I understand that. For others, a bit of accountability becomes a chore that interferes with their engagement. Students have reflected that tasks associated with reading pull their focus away from the text and onto the assignment. I get that, too.

I have been ruminating over my grading practices this year, taking notes on what is helpful and what can change next year as we progress, seeking practices which keep students accountable in non-intrusive, authentic ways. Letter grades in the English classroom can be tricky. Our content lends to subjectivity when grading. Add in the pressure for college-acceptable GPAs and authentic learning can be lost in the quest for an “A.” It can be difficult to accurately measure understanding, as well as the more essential habits for success beyond our classrooms–effort, improvement, depth of thought and questioning–with five letters. I am trying to shift from grades and points to accountability, effort, revision, second-laps, and reflection as tools for building skills and taking risks. I want anything I evaluate to have meaning and to be balanced by a lot of low stakes participation, effort, and reflection.

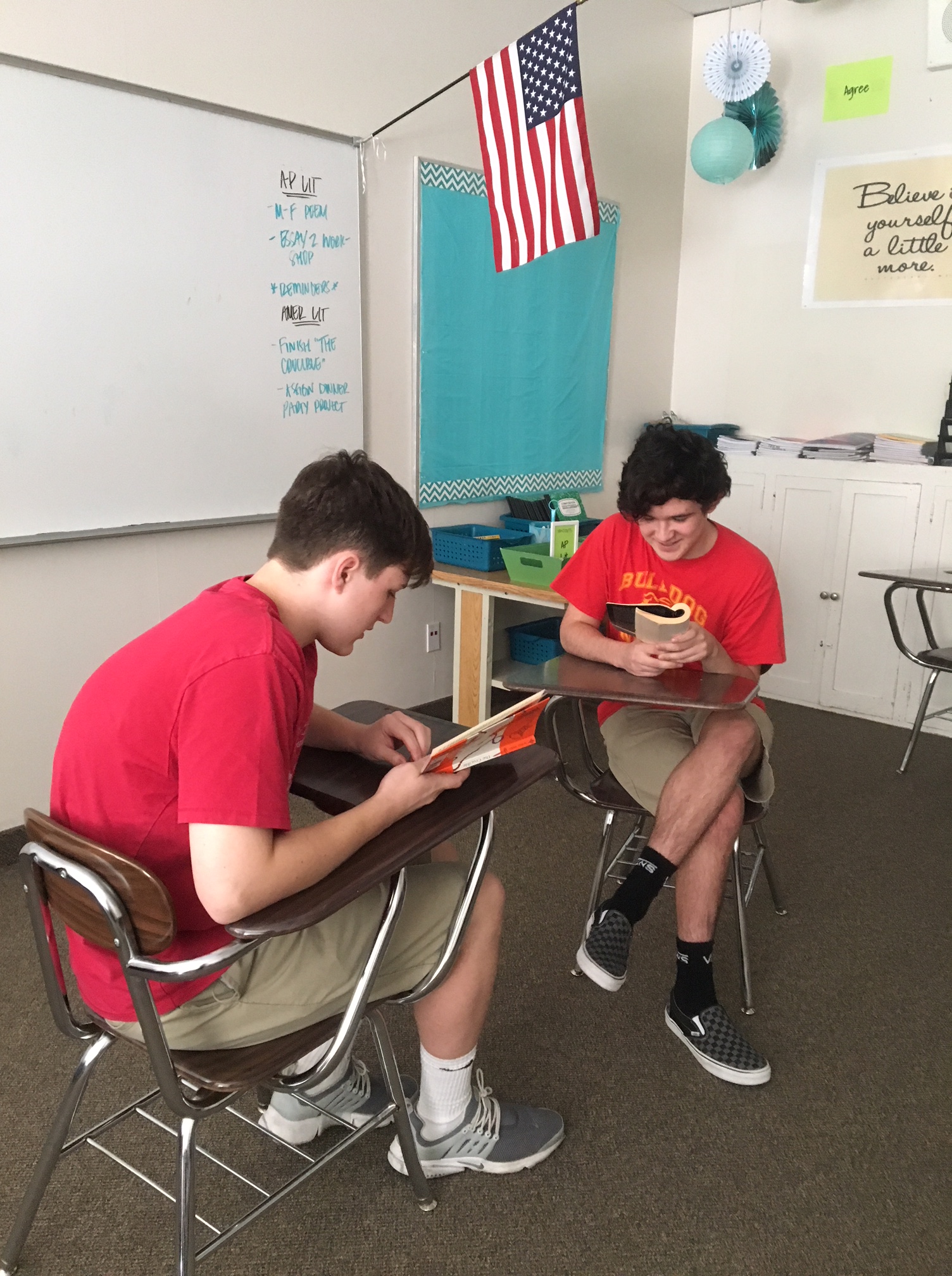

Book Clubs are like independent reading, just a bit more social. Why grade it with check-listy parameters? I wanted students to read, engage, and think with one another. To come to the table with questions, thoughts, and connections, like a college student would. To process challenging books together, like an adult book club would.

So I decided I would assign no accountability checks. Nothing. I only asked students to be accountable to one another, as adults would be in a “real” book club each week, with the schedule they set.

Knowing they wouldn’t be receiving a tangible grade or reward, I was concerned students would see this as an invitation not to read deeply, or that some wouldn’t feel invested in the payoff. However, my hope that our months of community building and sharing in reading experiences as readers outweighed my tinges of fear. Why not step aside and set them free?

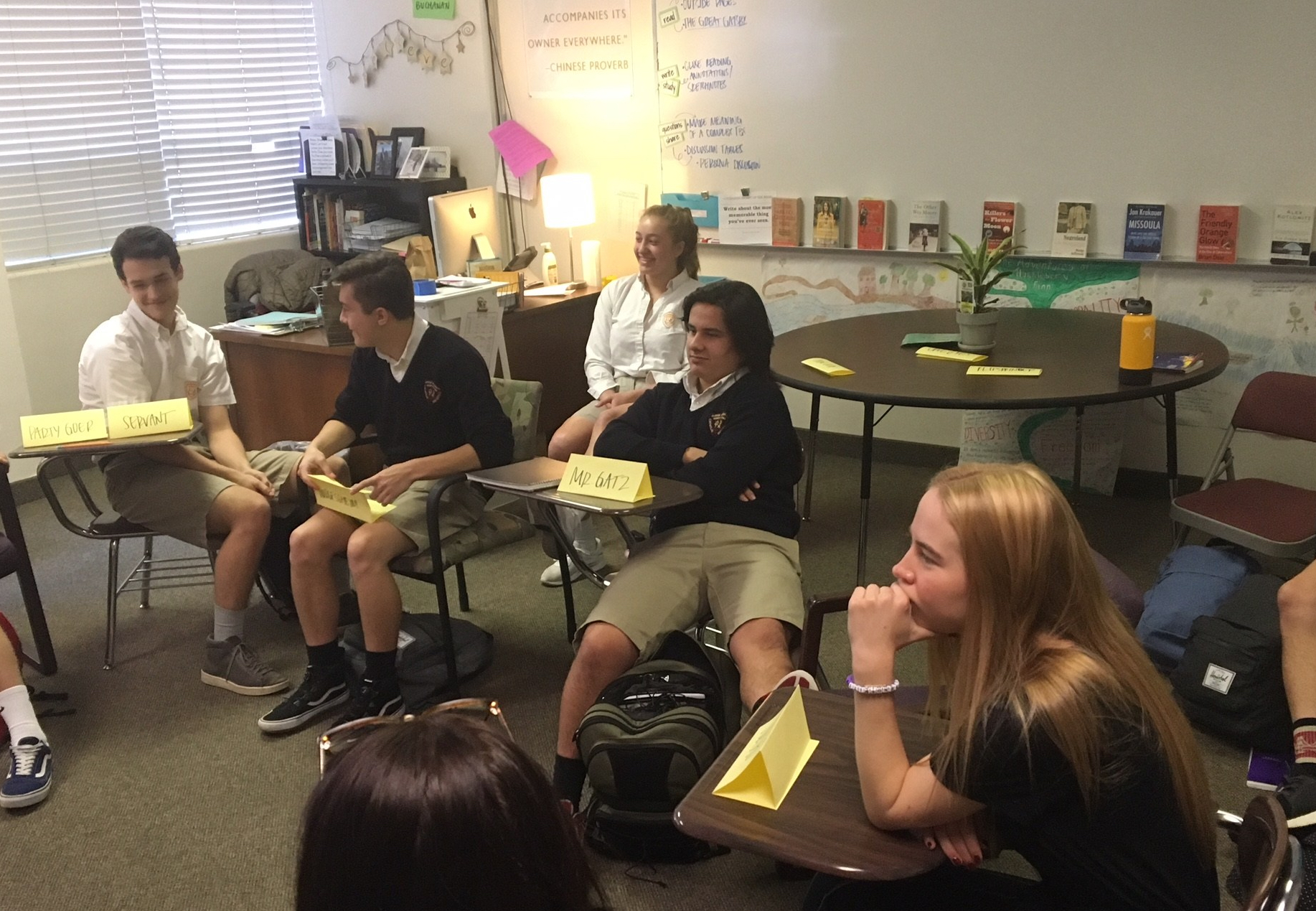

I gave Thursday’s class period over to the Book Clubs and student-driven conversations with the ask that students use the class period to process together.

Students owned it.

There wasn’t a lull in conversation on Thursdays. Student groups chatted with each other while I circulated and enjoyed their voices and insights. I wasn’t roaming the classroom with a clipboard or checking an assignment in while half listening. I was a floating member of each club (hence why there are no pictures accompanying this post!).

I noticed there were discussions about the gray areas of the books, like what is the Combine Chief Bromden references and what the heck happened to Nurse Ratched to make her the adult she is in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. I noticed the crew reading Ceremony worked to make sense of the non-linear structure and researched the myths of the Laguna Pueblo people. Readers of Brave New World connected the text to Oryx and Crake, a summer read, as well as our world. Readers of The Road hypothesized on the events before the book begins. Many students annotated their books, kept a notecard of questions to ask one another, took notes during the meetings, and referenced the text throughout their discussions.

There was no need to dangle a carrot in front of their noses or keep track of data to issue a grade. Students did the work because the elements were there: choice, time, conversation. They made meaning together, employing the habits developed throughout the year while practicing being adult readers–readers who read, engage, and think in a realm where there isn’t official accountability to turn in.

I’m not sure what my digital gradebook categories will look like next year, what practices and procedures I will put into place to promote authentic accountability, but I know I will challenge myself to step aside more often, to trust students will do the work if the environment is right.

Maggie Lopez is entering the fourth quarter in Salt Lake City upon returning from spring break. She is currently reading Hitler’s Furies by Wendy Lower. You can find her at @meg_lopez0.