My first day of teaching was going to be great, because I WAS PREPARED.

I wrote a speech, long hand, about 5 pages. It was going to communicate what students could expect from the class and what they should know about me. It was going to INSPIRE them. They would hang on my every word.

Forget all of the appalling things I just mentioned–you haven’t even heard the best part.

After I gave my approximate 35 minute speech, and students were drooling as a result of my awesomeness, we would have A DISCUSSION.

Drop the mic. Best teacher ever. My students will have a voice!

Needless to say, having never been in the classroom before, my first day was a shock. Most students did not want to hear a single word I had to say, much less ABOUT MYSELF. My voice was gone by the end of the day and I was in tears because I had no idea how to go back and do it for another round of classes the next day.

I had no idea discussions needed planning and structuring. I thought they just HAPPENED.

Oh–sweet, naive, extremely troubled Baby Mrs. Paxson.

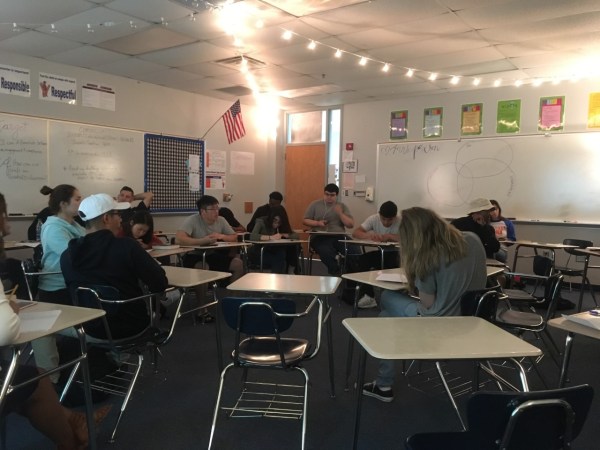

Almost two years later, we never have a discussion without some sort of structure. The structure can be minor, or it can be massive. It can simply be planning on my part, planning on the students’ parts, or it can be structure that I pull out of my back pocket to maximize of a discussion that materializes out of thin air. It can mean a different configuration of desks, or a script to which students can refer if they get stuck.

When we teach literacy, we can’t just command students to “talk.” We have to give them tools and materials and practices so that they are building their houses of reading, writing, speaking, and listening on a solid foundation, rather than a shaky one (insert your chosen Three Little Pigs invocation here).

Here are a few of my favorite ways to structure talk in the classroom, that can really work for ANYTHING from talking about books, to talking about real world issues, to reviewing pieces of writing, to students encouraging each other in passions and endeavors.

AVID Strategy, 30 Second Expert:

I learned this strategy through AVID, and it is so stinking versatile, it kills me. I’ve adapted it many times to fit what we need, but the underlying concept is in the script. I used this last during our Life at 40 Unit in which students were exploring desired careers and imagining/researching a possible life path. In order to get students thinking and talking about career paths, after we did a little bit of preliminary research and decision-making, I posted two sentence stems on the board.

I’m an expert about (desired career) because I found out that __________________________.

I will be an expert at (desired career) because I am (character trait), (character trait), and (character trait).

Now, after they fill out these sentence stems, here is where the magic happens. Students are required to pair up and repeat this script to a partner. Their partner must actively listen and repeat what this student said in their own words.

Here are some conversations I got to hear that day:

- “I will be an expert at physical therapy because I look on the bright side of things and I don’t give up on people.”

- “I will be an expert at cardiology because I have discovered that I can learn anything, and will work harder than anyone sitting next to me.” (Positive self talk, anyone?)

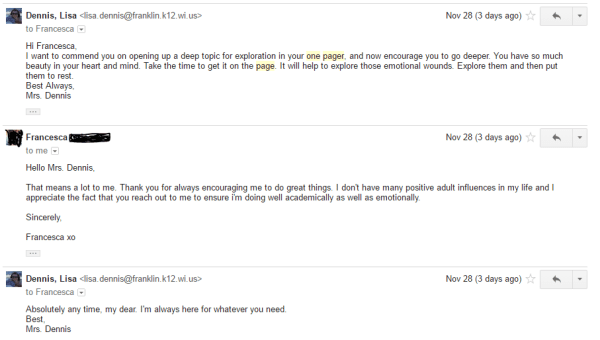

- (Repeating back to their partner) “I think you will be a great teacher because every time I talk to you in class, I feel heard and understood. You stated you were a good listener, and I have experienced that from you.”

This is just a small glimpse into the conversations that can happen with 30 second expert. Students feel silly at first, and they joke A LOT with these scripts, but even so, if you change your thoughts you can change your world. Sometimes changing thoughts means changing the way you talk about yourself to others. This allows students to phrase things they’ve just learned or mastered in a way that helps them realize they have added to their learner toolbox.

Speed-Dating:

We are major speed daters over here at 3TT. We speed date books ALL THE TIME. I’ve also found that the speed dating format is golden for a lot of things such as when students bring in their own news articles for an assignment, giving post-it blessings, reviewing and revising writing, trying different mentor sentences and sharing, or really any situation in which you would like to allow students to have face-to-face time with many different ideas and possibilities. You could also do 30 second expert in a speed-dating format!

Socratic Seminar:

I am by no means an expert on Socratic Seminar, but many different educators have different ways to get students talking about higher level questioning in a group setting. B’s Book Love has some of my favorites. In 822, we’ve tried fishbowl, whole class circle, passing stickies, and inner/outer circle with a live Twitter Chat. They’re all great. When my kids hear Socratic Seminar, they know I mean serious business, so this usually elicits slightly more academic talk.

Ultimately, structured talk promotes confidence and community in the classroom because it not only communicates high expectations, but it gives students the building blocks to reach those expectations and with skills they will carry into the real world!

How do you structure talk in your classroom? Have you learned any tricks along the way? Share them with us below!

Jessica Paxson is an English IV and Creative Writing teacher in Arlington, TX. She usually takes on major life events all at once rather than bit by bit, such as starting graduate school, buying a house, going to Europe, and preparing for two new classes next year. If you enjoy watching her make a fool of herself by being unbearably vulnerable, you can catch more of that over at www.jessicajordana.com. Follow her on Twitter or Instagram @jessjordana.

Grading, grading, grading.

Grading, grading, grading. Good, old-fashioned, print-it-out-and-bring-it-to-class-and-turn-it-in assignment submission.

Good, old-fashioned, print-it-out-and-bring-it-to-class-and-turn-it-in assignment submission.

We teachers often talk too much.

We teachers often talk too much.

aforementioned tasks, what should I start with?

aforementioned tasks, what should I start with?