Written in the spring of 2017, Margaret Lopez reflects on the value of purposeful communication and strategies to get kids to create questions that get at the heart of a topic and generate meaningful discussions.

All year, my juniors and I have been workshopping writing and reading different texts for a range of purposes, pairing fiction and nonfiction for some whole class studies (Death of a Salesman and Outliers–a hit! 1984 and current events surrounding fake news and government–loved it!). I realized a skill I hadn’t closely instructed, we had just “done,” was intentional classroom discussions. As my juniors prepare to be seniors,  college students, and individuals in the workplace, they need to speak purposefully and ask intentional questions. I want them to be able to say something, not just anything From this reflection, and students’ interest in recent protest movements and community issues in Chicago, a social justice unit based mainly on speaking and listening with low stakes writing was born.

college students, and individuals in the workplace, they need to speak purposefully and ask intentional questions. I want them to be able to say something, not just anything From this reflection, and students’ interest in recent protest movements and community issues in Chicago, a social justice unit based mainly on speaking and listening with low stakes writing was born.

I selected three books for students to chose from, and those choices became their lit circle groups. Students could chose from Half the Sky which discusses female discrimination across the world, Ghettoside which examines policing in a predominately African American community outside of LA told by a reporter who spent years reporting on crimes in the area, or Hillbilly Elegy, a memoir about growing up in Appalachia.

Throughout the unit, we have followed the same routine:

Mondays are for lit circles, Tuesdays are for extension activities with nonfiction, and on Wednesdays, we discuss all three texts together in a Socratic Seminar. My goal was a lot of low stakes writing and fruitful discussion.

I think there is a reason that discussion is a central component of the English classroom, as it builds community, facilitates deeper or new thinking on a topic resulting from other perspectives, and is a college and job skill we have the duty to foster and refine in our students. However, students need to speak, listen, and ask purposefully. My students know how to talk–at my small school, where classes can be between 6 and 16 students, class stalls if they don’t have anything to say. The awkward silence lingers. Then someone says any random thought they have just to break the silence. But there is difference between saying anything and saying something. To elevate students to say something about the injustices across the texts, not just anything so that awkward silence doesn’t linger too long, I began with questioning skills.

It is challenging students to take the idea they’re wondering about and want their peers to contemplate and thinking about it backwards, writing a question that doesn’t give away their opinion, lead peers right to the answer, or simply confuse others.

We began by running through the list of essential questions from this school year and reviewing their quick writes on the topics from throughout the year. I asked students what they noticed about the questions, many came to the conclusion that the questions are BIG, meaning they have more than one answer, but those answers aren’t definitive or “right.” From there, we looked at a list of plot-based questions I made about the first chunk of their reading to compare the lists of questions. They easily noticed these questions were the opposite of essential questions, meaning they had a limited scope of what response could be correct or on the right track.

Great, they can notice the difference. Now to teach them to apply this to their own questions. Thank the teaching gods and goddesses for Jim Burke’s What’s the Big Idea?. I used his entry points into teaching questioning around three types of questions: Factual, Inductive, and Analytical, having students label their own questions as one of the three types. Then, we worked on revising after I modeled some examples. I challenged students to move beyond the factual so we could get to the big ideas and scale up Bloom’s Taxonomy.

Jacely revised her questions to get to the heart of her concern, which was why law enforcement doesn’t seem to care about women that are in trouble:

- Factual: On the very first page of chapter 2, what does Nick ask the Officer about regarding trafficked girls?

- Inductive: Kristoff asks an Officer about what exactly they look for and then mentions if they look out for trafficked girls and the officer mentions there isn’t much to do about them. Why do you think these officers seem to not care about this huge issue?

- Analytical: What implications does this have on the community? Women’s futures? Are there issues with law enforcement in the communities in your books?

Mishawn revised to include more perspective and connection:

- Factual: Why is the crime rate so high in Watts?

- Inductive: What allure do gangs have for the young people in the community? How does this create a cycle of violence and crime?

- Analytical: What factors, both historically and recently, have lead Watts to become a breeding ground for criminal activity? In your opinion, which factor is/has been the most detrimental?

I also provided students with question stems as a guide and encouraged students to use these until they felt comfortable framing their questions. By the end of the unit, student questions were synthesizing the three texts and major ideas. I noticed students would lead with a question geared more towards their text, then extended the question to the other two text, thus inviting in more conversation and fluidly moving between inductive and analytical questioning. The discussions moved from inner to outer, from focused on one book to all three books.

Jordan: How does Leovy expect the reader to believe in the good homicide detectives while at the same time giving examples of racist and uncaring detectives? What contradictions exist in your book’s community? Do these lead to an imbalance of power or other injustices?

Ben: Isolation is discussed by Vance as one reason leading to a disconnected, stalled hillbilly society. How are the people in your text isolated, whether by location, proximity, cultural norms, or otherwise? Does this perpetuate the problem or is it a solution that hasn’t been capitalized on?

To springboard Wednesday’s seminars, we often pre-thought through the big ideas for that chunk of reading as a way to anchor thinking and create a common entry point into the seminar, and also, so students had something to say.

- Google Doc Quick Collaboration: I posted some initial questions on the google doc to get students thinking, then watched the entire class collaborate on 1 document–so cool! I limited this pre-thinking to about 3 minutes so students didn’t type all of their discussion points. I also left this projected during the seminar, serving as an anchor chart and inspiration for more questions. So easy. Minimal prep. Great results!

- Discussion Tables: I made three table tents at three different tables in my classroom, each with a common idea and thread that occurred during that chunk of reading. I gave students two minutes to discuss how each topic related to their book. After two minutes, they moved to a new table and could shuffle up their group. Again, minimal prep and 6 quality minutes of pre-thinking.

- Essay Highlights: Students wrote for 20 minutes about the central injustice in their novel, justifying why that, out of all the intersected issues, is the most pressing for the community in the book. I then typed the major argument from each student’s essay and used it as an entry point into a Wednesday seminar. Students were able to see the something their peers had to say, understand how perspective and perception shade one’s reading, and make connections across the three texts.

- Pass Around: I asked students to write a line from their book that really just hit them in the gut and explain why. Then, students passed them around the room, spending a few seconds reading what their peer had been most impacted by and why. I actually couldn’t stop students from talking. Across the table, students were making “OMG” eyes at each other, whether it was a connection with their lit circle peer or shock over what a peer had written about from another text, the conversation was immediately started.

As I have listened to each small group discuss the same texts, it was amazing to hear how the conversation differs from class to class. I wanted students to experience that, to give them a chance to expand each others’ thinking. I assigned two digital seminars using our school’s digital platform, and while this is nothing crazy innovative, students posted and responded, I noted many benefits from this type of “discussion”:

- Students experienced new perspectives and interpretations of the text from their peers in other classes, and I found more students sharing personal anecdotes–students were sharing their personal experiences with discrimination and inequalities.

- Shy students or those that need more process time were the space to contemplate, revise their thinking, or deepen their response by not having to think on the spot as they would during an oral discussion. I have many exchange students from around the world (China, Spain, Thailand, and Italy), who have the extra task of interpreting, decoding, and thinking in two languages By writing, students had more time to think and contribute at their pace.

- Students were more thoughtful in their responses and more likely to use text evidence to support their argument or open their classmates’ eyes because they aren’t so “on the spot.” Students used evidence from the book, as well as other articles we had read, thus adding rich context to the discussion.

- Students had another opportunity to practice practical writing for college. Many college courses require blog post or digital contributions, and the reality is that most of my students will take an online course at some point in their academic or professional lives, too.

- Students received real time feedback on their questions. If no one responded, maybe the question was unclear, too narrow, or too broad. Student-led formative assessment–a new trend?

- Students had a time and space to learn about digital etiquette and practice, something very important as Snapchat and Twitter become accepted means of communication. As students move into their post-secondary endeavors, they may be communicating with bosses or professors via email and must communicate clearly, without a misinterpreted tone. We discussed how to politely disagree and how to ask a follow up question instead of answering with bias, as well as the time and place for proper mechanics.

- I made time to write beside them, contributing to the discussions, too.

Although these strategies were successful in moving my students beyond saying anything at all to fill the void, the best part was how moved my students were by the injustices that exist in our world. They spoke with such compassion and concern for those suffering they no longer seemed to be kids, but young adults.

Maggie Lopez has six years of teaching experience at large public high schools in Louisville, Houston, and now Chicago. A graduate of Miami University, she had the pleasure of learning from the workshop masters and is on a continual quest to challenge, inspire, and learn from her hilariously compassionate juniors and seniors.

audience.

audience. I have so much hope for our profession, our students, and our society.

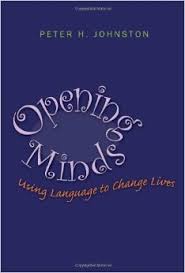

I have so much hope for our profession, our students, and our society. I’ve been reading Peter Johnston’s excellent Opening Minds with my preservice teachers, and it’s a must-read. One of the skills Johnston says the most open-minded students possess is that of social imagination, or being able to understand “what others are feeling, to read people’s faces and expressions, to imagine different perspectives, to make sense of abstract ideas, and to reason through this.” In other words–empathy on all levels. It strikes me that this is both a reading skill and a life skill.

I’ve been reading Peter Johnston’s excellent Opening Minds with my preservice teachers, and it’s a must-read. One of the skills Johnston says the most open-minded students possess is that of social imagination, or being able to understand “what others are feeling, to read people’s faces and expressions, to imagine different perspectives, to make sense of abstract ideas, and to reason through this.” In other words–empathy on all levels. It strikes me that this is both a reading skill and a life skill. The next day in class, we’ll refer back to the article before beginning independent reading time. “As you read today, pay attention to the characters in your book–are their lives more happy, or more meaningful?”

The next day in class, we’ll refer back to the article before beginning independent reading time. “As you read today, pay attention to the characters in your book–are their lives more happy, or more meaningful?”