This morning, with the new audiobook release of Don Graves’ Children Want to Write (narrated by two of our teacher heroes, Penny Kittle and Tom Newkirk!), I’m thinking about that true fact: children do want to write. We all do. Our minds are, after all, made for stories.

But to tell our stories is a challenge in so many ways. We live in an age of distraction, many of us are often silenced by society, or we struggle to find an audience we trust.

But most of all, many of us don’t know how to tell a story if we’ve never seen a story like ours told before.

Stop and think about this concept, etched in my mind by Dr. Rudine Sims Bishop with her concepts of books as windows, mirrors, and doors. I’ve spent a good deal of my planning time outside of school finding books that can act as windows, mirrors, and doors for my students to either see through, see themselves in, or walk beyond.

But I’m interested today in the way we go further with that discovery. Once you find yourself in a story, how can you tell your own? I realized years ago that I wasn’t just reading voraciously to find my own story; I was looking for a storyteller with whom I could identify: a living, breathing mentor text. I found it when I met Penny Kittle at the New Hampshire Summer Literacy Institutes, a teacher-writer-mother who counseled me on sustainable ways to balance my young children with the work of teaching well.

Until I met Penny, and was bolstered by her support and willingness to share her own story of struggling to be a mom-slash-teacher, I didn’t know how to tell my story. And until I did, I couldn’t be a living, breathing mentor text for my own students, who were thirsting to tell their own stories.

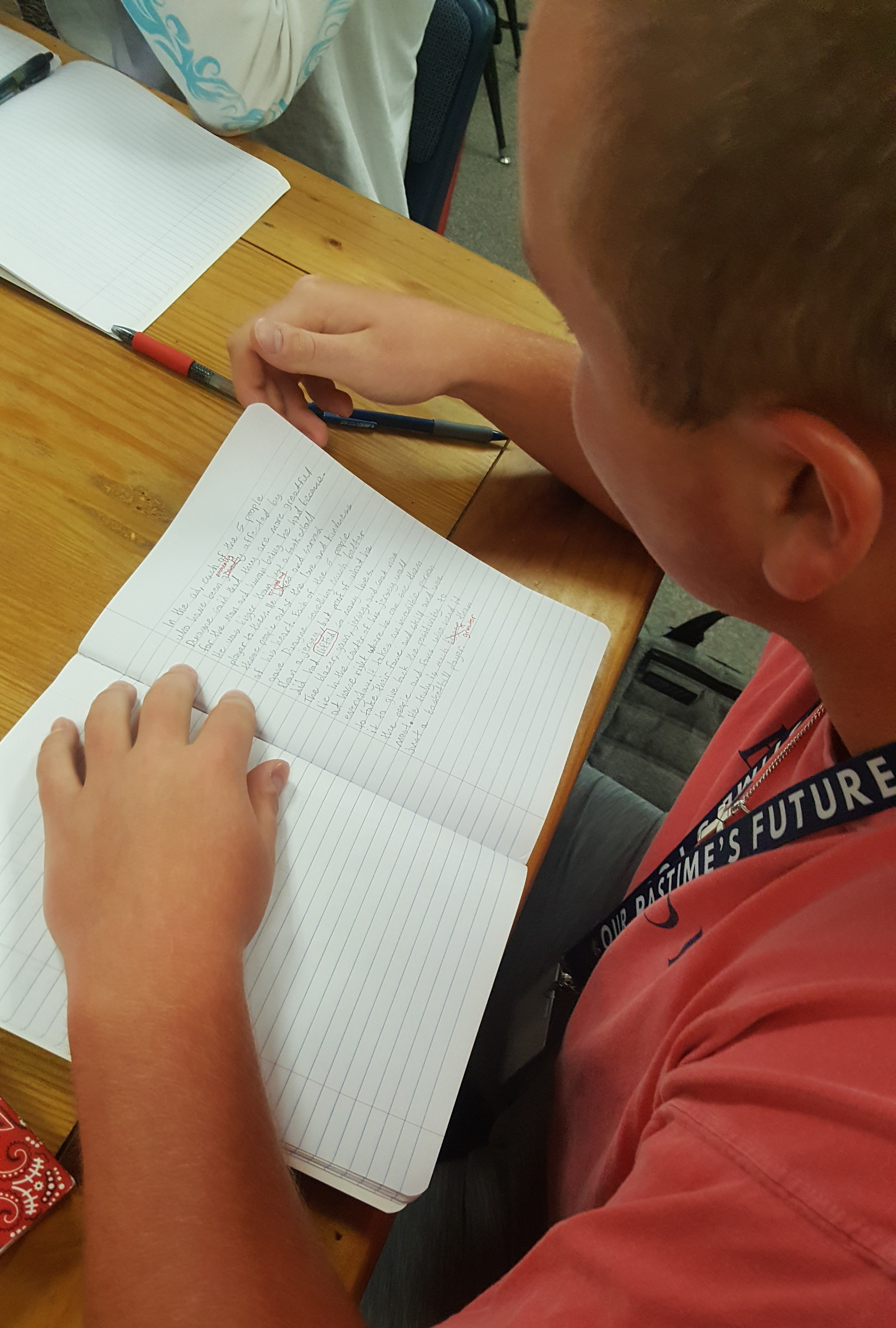

As English teachers, we are blessed to have the opportunity to be that mentor text for our students: teacher-writers who practice, every day, finding and telling stories that resonate. It’s my favorite part of this work, the joy of getting to read and write powerful stories alongside our students. We can offer space for storytelling in our classrooms in three key ways–with vibrant mentor texts, opportunities for playing with genres, and the time to tinker and devote our study to narrative.

- A well-stocked classroom library, frequent and varied book talks, and mentor texts that flood our students with diverse voices and stories offer our students windows, mirrors, and doors through which they can discover empathy for others and themselves. Seeing a range of stories disrupts the concept of “normal” and helps students see the world in shades of grey, rather than just black and white.

- Quickwrites and mini-lessons that allow students to play with genre offer possibilities for storytelling they may not have considered: poems, lists, fiction, memoirs, vlogs, podcasts, and multimodel texts show how we can allow the concept of story to flourish in any medium.

- Time to write: every day, in quickwrites and in workshops, but also over time–when we devote more than just a unit, or a quarter, or a set of standards to the idea of story. We put our money where our mouths are when we return to story again and again, through concepts of argument, informative writing, or creative fiction and nonfiction.

When we offer our students these ingredients, we create a recipe for storytelling that brings authenticity, relevance, and power to our classrooms. A community of readers and writers can be transformed into a workshop of storytellers, who speak and listen through the powerful lens of narrative.

We invite you to share in the comments how you bring story into your classroom!

Shana Karnes loves to read, write, and find stories everywhere in Madison, Wisconsin alongside her two young daughters, hardworking husband, and inspiring teacher friends. Connect with Shana on Twitter at @litreader.

I’ve asked students to complete, every book I’ve matched to a reader’s interest has given me insight into who these young people are as individuals with backgrounds, cultures, fears, failures, dreams and desires. Just like me, they cling and pounce and clamor after hope.

I’ve asked students to complete, every book I’ve matched to a reader’s interest has given me insight into who these young people are as individuals with backgrounds, cultures, fears, failures, dreams and desires. Just like me, they cling and pounce and clamor after hope.

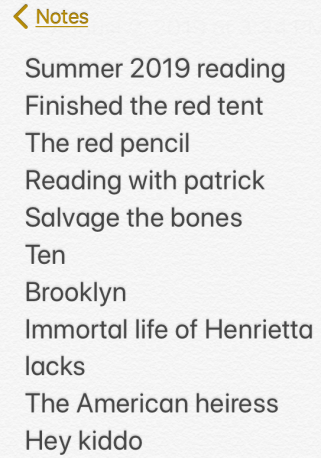

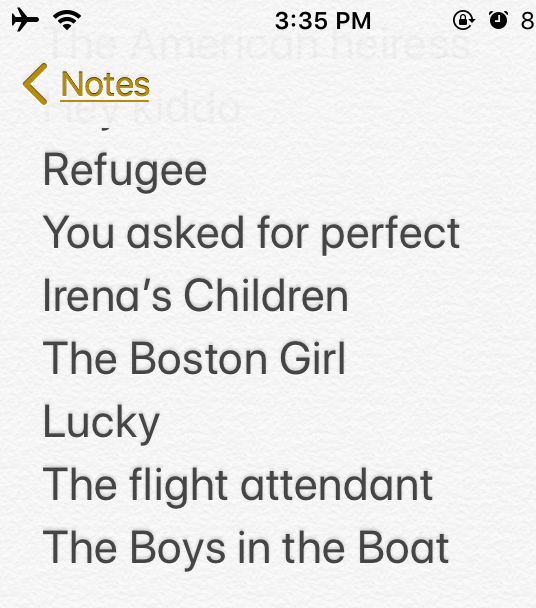

I’ve kept track in the Notes app on my phone, and it’s super easy to keep track this way. I could have added how many pages were in each book, genre, authors, etc, but those are easy things to look up later, so I just included the titles in my own list.

I’ve kept track in the Notes app on my phone, and it’s super easy to keep track this way. I could have added how many pages were in each book, genre, authors, etc, but those are easy things to look up later, so I just included the titles in my own list.