Teaching is a reflective practice. If you’re doing it right, that is.

We question, we research, we dig deep to update, invigorate, and refresh our work on a daily basis. And while this can be utterly exhausting (I think we need to investigate the ingenious cultural practice of siestas), it’s also exciting. As we push ourselves to grow and change as teachers, we impart that commitment to be better to our students.

I remember when I was student teaching several (cough, cough) years ago. The English and Social Studies departments shared an enormous office, and I was lucky enough to be afforded some space in that room to work. The fresh-faced 21 year old with boundless energy and enthusiasm for making a difference and connecting with “kids” (I was teaching 18 year olds. I’m pretty sure I was in elementary school with one of my students).

Then, I met *Mr. Pumblechook. (Names have been changed to protect the identities of very nice, well meaning people whose educational practices make me shutter.)

Pumblechook was a social studies teacher with perhaps six or seven years under his belt. He had a bright smile, hearty laugh, great expectations for his students (I had to. Thanks Dickens) and a file cabinet.

But this, ladies and gentlemen of the jury ( got serious quick, didn’t I?)this was no ordinary file cabinet. For in this file cabinet was a collection of folders. And in those folders were lesson plans.

One folder for each day of the year containing (because I pretended to be impressed with his organization and asked to see): a lesson plan, several worksheets to make copies of (even leftover handouts from the year before), and overhead slides of prewritten notes.

Was I student teaching in 1962? No.

Was I student teaching under a dictatorial regime? No.

This was 2002, people. Suburban Milwaukee.

And every time I tell this story to fellow educators, they nod, and I hear similar stories of educators from days gone by. Worksheet after worksheet, recorded lessons from first hour played to subsequent hours, teachers knitting in the back of the room, and countless acts of readicide across the land. Is seems Mr. Pumblechook had good historical precedent for imparting knowledge to children by opening up their brains and pouring in the same ideas year after year without regard to their role in that programming or real world applications of classroom material.

Enter: My classroom last week.

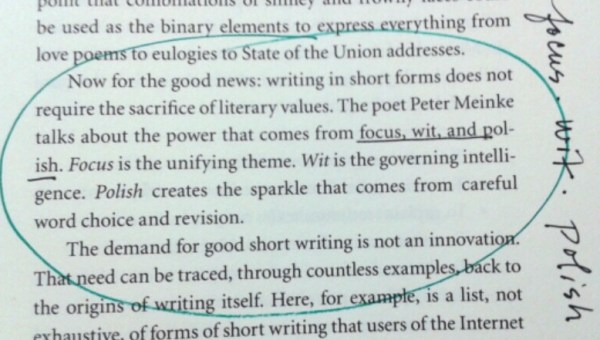

My AP students are armpit deep (my quip to convey complexity over the waist, but less perilous than the nose) in literary analysis. I wrote last week about our journey with diction analysis, as we got down and dirty with how an author conveys meaning with words.

Along my merry way I skipped, confident in this unit that I’ve taught several times, the tweaks I’d made in planning it for this year (updated mentors, current event references, jokes that students last year hadn’t heard yet – he he), and last year’s solid AP test scores. Not quite a folder for each day, but not too terribly far off either.

Then, I read Rebekah O’Dell’s post from Moving Writer’s, “Three Reasons Literary Analysis Must be Authentic.”

Gulp. Authentic.

I (shamefully) hadn’t really thought of that. I was preparing my students for the AP Language test. Wasn’t that authentic enough?

Of course, the skills of analysis are invaluable. Critical thinking across the curriculum is bolstered by the development of analysis skills which help students recognize patterns, decode information, compare and contrast concepts, classify elements under examination, and utilize inferences to support ideas. As one of the elements utilized by the College Board to determine students’ readiness for college level curriculum in English, rhetorical analysis is obviously important. The traditional essay format is required to pass this test and the analytical skills necessary to do so are a benefit to students far beyond the classroom.

But here’s the rub…

Even AP readers are looking for students to write outside the box. Yes, the skills of analysis must be present. But top scoring papers are those that challenge convention, take risks, and (I’m hanging my head in shame here) speak to a more authentic and far-reaching audience.

O’Dell’s post, like literary providence, reminded me that I needed to climb out of my car with tinted windows (I’m in here doing my thing. Nothing to see here) and pick up a mirror to reflect why I was doing what I was doing.

Her 3 key reflections on teaching literary analysis hit me right between the pencils. She reminds us that:

- Our job isn’t to produce English teachers.

- Writers need models in order to write.

- The traditional academic, literary analysis essay hurts student writing.

So, am I hurting my students with what I’ve been doing? Absolutely not.

Could it be better? Absolutely, Mr. Pumblechook, because they might be better at formulaic writing with what I’ve been working on, but we’ve taken some steps back in their growth as authentic writers.

To address each of O’Dell’s points, which I felt compelled to do immediately (I had the mirror up and didn’t like what I was seeing), I changed some plans for this week and next.

- Our job isn’t to produce English teachers: I have to tell myself this more and more. O’Dell reminds us that 2% of college students major in English, and of those 2%, only 1% will enter professional academics.

It did occur to me though, that our students will need to engage with the world around them and likely need to synthesize ideas in order to share them. As such, I had my kids choose editorials on current events and topics of interest to present 1-2 minute speeches on. They needed to make claims about how the author achieved his/her purpose through DIDLS.The fluency of their writing for these speeches has blown me away. We’d been “writing analysis” last week, but none had the same voice, passion, or deep analysis that these had. Speaking the analysis had the power to remove the formula. Students concentrated on engaging their audience in a way that a practice AP prompt could not replicate.

When my students sat down to write a full AP analysis practice today, I reminded them of how they had to work to capture the audience of their peers through their speeches, and that the nameless/faceless AP writers still wanted that same engagement. They want students to be successful on the test. This exercise seemed to solidify that and afford my kids the opportunity to reignite that natural voice we have been working with all year.

Katie presents her editorial analysis speech this morning

A quick Google form that I fill out as students are speaking provides immediate feedback via email

A sample of the detailed feedback on both content (helps with literary analysis prep) and public speaking (a real life skill for all)

Students give peer feedback on the rhetorical analysis they heard, as well as the speech overall.

- Writers need models in order to write: I’ve been using student samples from AP to accompany the prompts we’ve been analyzing for years. That’s honestly helpful. I have students score them and discuss with peers what constitutes a high, middle, and unacceptable essay according to AP so they can apply or avoid the same ideas.

However, those high scoring essays were always met by my students with comments that suggested that top scoring essays held some undefinable magical quality.

What is it? Style.

Those essays, as I said earlier, not only develop complex ideas, but they do so in a way that keeps the reader engaged.To work with this, I’m going to share with my students some of the literary analysis that O’Dell’s post links to as well. The Atlantic‘s “By Heart” where authors share their insights on their own favorite passages in literature, is a website that makes literary analysis real, full of voice, and peppered with references to texts/authors my students know.

My post a few weeks back on Arts and Letters Daily is another place we’re going to explore. How do writers write about texts without using a five paragraph essay? How can we, as Penny Kittle says, stand on their shoulders as writers and work to write as they do?

- The traditional academic, literary analysis essay hurts student writing: We want our students to be able to master the structure and form, but yet we want them them to break free of it too.I’ve often told my kids over the years that you have to know the rules in order to effectively break them.

Maybe it’s true. Maybe, I just don’t have them break them soon enough and get to that authentic voice for an authentic audience.Because there, in the place where they have something to say with confidence, passion, precision, and critical thoughts developed by honed skills, will they bridge the gap between possessing the skills we want them to master and making their writing shine with the creative use of those same skills.

And now…it’s Wednesday morning and the lovely Tricia Ebarvia just ran a post about authentic audience through blogging. I’m headed there next.

I should just carry a mirror. I need it. Always.

How do you help move students move beyond the traditional literary analysis? We’d love to hear your ideas in the comments below!

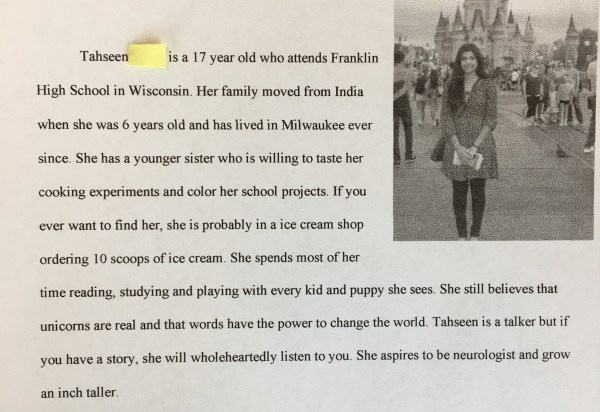

Lisa Dennis teaches English and leads a department of English superheros at Franklin High School near Milwaukee. A joke her students haven’t heard yet, but soon will, is: Why did the librarian miss the conference? She was overbooked. Her students are sure to chuckle, if not pumblechook (used as a verb with creative credit to Dickens), at that one.

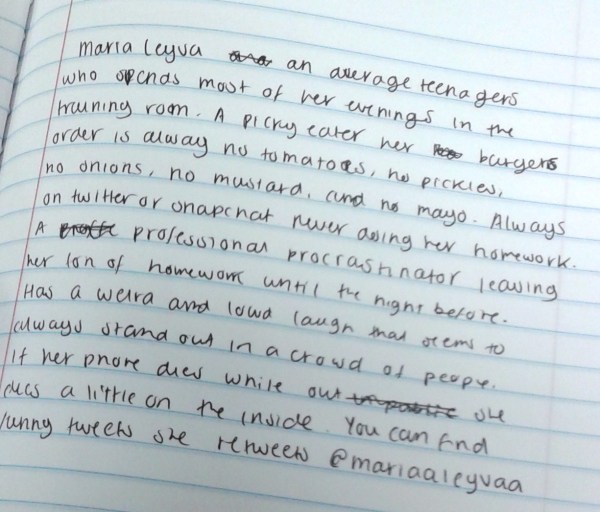

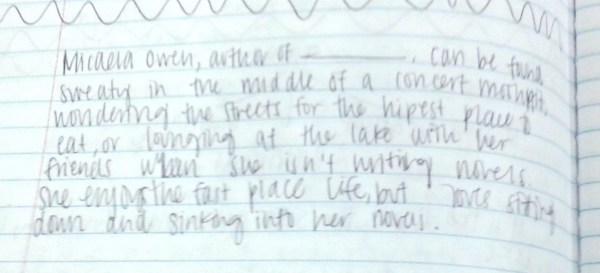

I prepared first by reading the inside back covers of some of my hardback YA literature. I chose four bios with similar elements: Andrew Smith,

I prepared first by reading the inside back covers of some of my hardback YA literature. I chose four bios with similar elements: Andrew Smith,

I reminded students as they write over the next few days — finishing their multi-genre projects, their last major grade — to write with intention, to write in a way that shows the answer to the last question I’ll write on the board this year: How have you grown as a reader and a writer?

I reminded students as they write over the next few days — finishing their multi-genre projects, their last major grade — to write with intention, to write in a way that shows the answer to the last question I’ll write on the board this year: How have you grown as a reader and a writer?

This year, as I made the venture to RWW, I knew I would need to read lots of buzz-worthy books, simply for the purpose of recommending. Needless to say, I have slowly been broken down from my rigid ways. It’s because of this anti-bandwagon mentality that I am so late to the Anthony Doerr party, particularly in respect to

This year, as I made the venture to RWW, I knew I would need to read lots of buzz-worthy books, simply for the purpose of recommending. Needless to say, I have slowly been broken down from my rigid ways. It’s because of this anti-bandwagon mentality that I am so late to the Anthony Doerr party, particularly in respect to

The Promise written by Nicola Davies and illustrated by Laura Carlin is a beautifully crafted story of a girl growing up in a hardened city. After stealing a purse from a pedestrian, the main character makes a promise out of desperation, only to realize that the purse she has stolen has no value and is instead full of acorns, which she must now plant across the city. The story reads more like a poem and has a cyclical ending that allows students to see the succinct structure of a short story.

The Promise written by Nicola Davies and illustrated by Laura Carlin is a beautifully crafted story of a girl growing up in a hardened city. After stealing a purse from a pedestrian, the main character makes a promise out of desperation, only to realize that the purse she has stolen has no value and is instead full of acorns, which she must now plant across the city. The story reads more like a poem and has a cyclical ending that allows students to see the succinct structure of a short story.