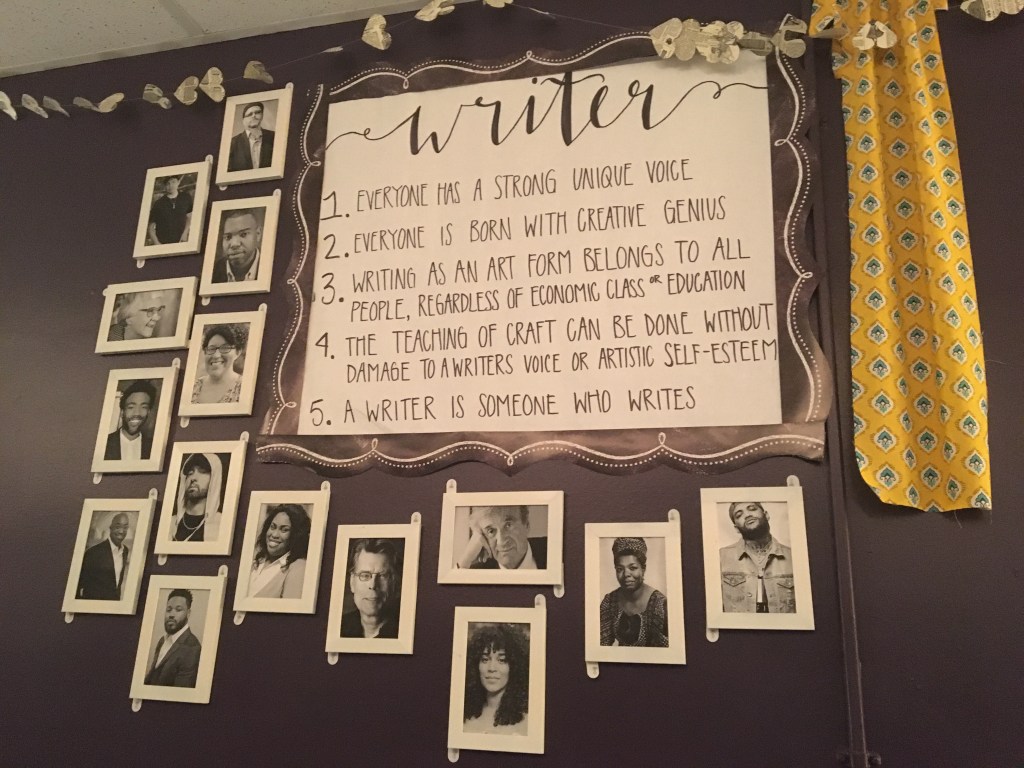

My job as an English teacher is to empower my students to discover, identify, locate, rediscover, find, and fall in love with the books that speak to their souls and their hearts.

In order to make that happen, I have to have a dynamic classroom library. A year and a half ago, I didn’t have anything on my shelves in my classroom, but because my school, my family, and my colleagues are on board with the vision of robust classroom libraries, my library looks a whole lot better than it did then.

My shelves when I first saw my current classroom

My shelves after a week or two of procuring books

My current shelves

We’ve raided the school book room, collected our main library’s discards, purchased books off of facebook and other “garage” sale type of venues, and we bring back hundreds of pounds of second hand books in our suitcases at every opportunity. (I live in Nicaragua, which complicates the book buying at times.) We spent our entire English department budget on classroom libraries last year, so this fall we felt like kids in a candy store when we were setting up our new classroom libraries.

Each time we are blessed a new influx of books, we have to think about storage, and more importantly, organization. It’s essential that we store and organize our books so that students will be drawn to the shelves and compelled to read new books.

I haven’t had any experience that tells me that labeling and micro-leveling books is what makes my students want to read. Quite the opposite. What I read also tells me that labels aren’t for public display on the spines of books or on the front of organizational book baskets. They are tools for teachers to use, which may help them with a cursory understanding of texts before they can get to know them better.

My job as an English teacher is to empower my students to discover, identify, locate, rediscover, find, and fall in love with the books that speak to their souls and their hearts.

My experience and observations tell me that organizing my books by general level and genre is what works best for my classroom library. That rotating book displays pique student interest in titles they might not have noticed or cared about in the past. That topic, passion, and enthusiasm can sell a book to a student a whole lot more convincingly than a level or a label can.

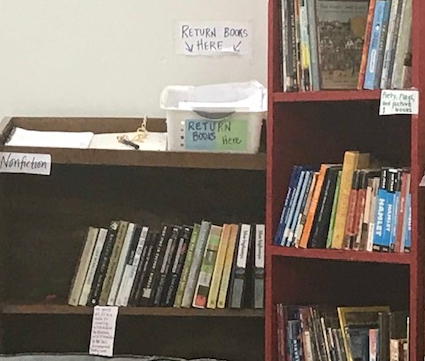

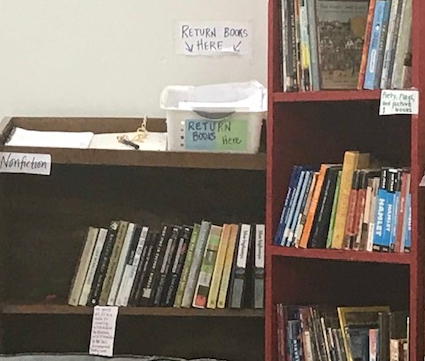

My classroom library is split into four basic sections:

- middle school fiction

- young adult fiction

- contemporary fiction

- nonfiction

I do this out of necessity: I teach three sections of seventh grade English and two sections of AP Language and Composition. It’s important to have some distinct sections for these students so they at least have a starting place when they browse for books. They do tend to meet each other in the young adult fiction shelves, and there isn’t much that stops them from “shopping” on all of the shelves.

Within those four sections I have subsections, however.

I have grouped some middle school fiction into some general categories: magic/fantasy, mystery/scary, realistic fiction, historical fiction, books in a series, sports, and shorter/easy reads.

In the young adult fiction section I caved to a student who really wanted a romance section (why not? I thought). I’ve also grouped some of these books into a “books in a series” section, a mystery/horror section, dystopian, and a sci-fi/fantasy section. The section on World War Two shelf was created because I have a number of students who are gravitating towards that topic right now. It’s not comprehensive, and it mixes middle level, young adult, contemporary fiction, and nonfiction, but it is what’s working for my students right now, so it will stay for at least a while.

That’s the whole point. Our classroom library organization is based on what works for my students. It wasn’t prescribed by any “experts” or mandated by anyone outside of my classroom. It’s authentic, preserves student emotions and privacy, and the shelves are open to whomever would like to browse them.

There is a tiny bit of leveling – three levels plus nonfiction, but this leveling is more about maturity and content than text leveling. It’s certainly not the microlevels of Lexiles, A-Z, or AR that some libraries employ. It’s helpful rather than restrictive.

Because the books are organized into these smaller topic or genre sections, students have a helpful place to start looking that isn’t rigid. I feel like it’s the best of both worlds because it gives students a direction and a guide, but not rules or rails they have to live between.

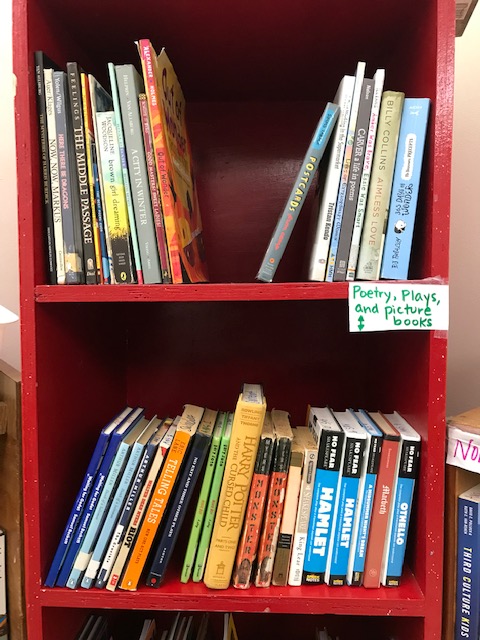

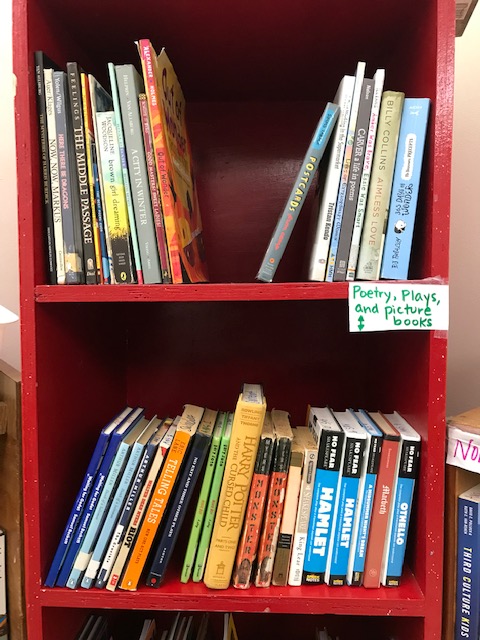

Simply because of the space and shelves that I have in my room, I’ve added a subgroup of poetry, plays, and picture books section in the nonfiction corner.

This is a corner that needs some work. As I add titles to my classroom library, I will deliberately look for poetry and drama, as well as relevant picture books to add to these shelves.

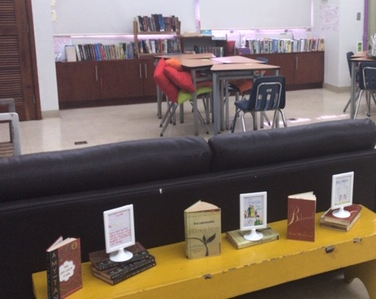

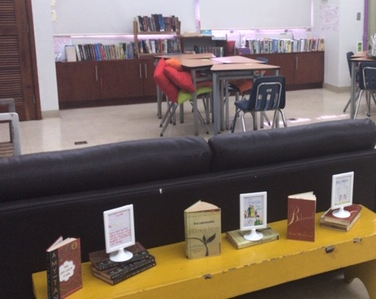

While I have these semi-permanent organizational ideas, I also have some rotating book displays.

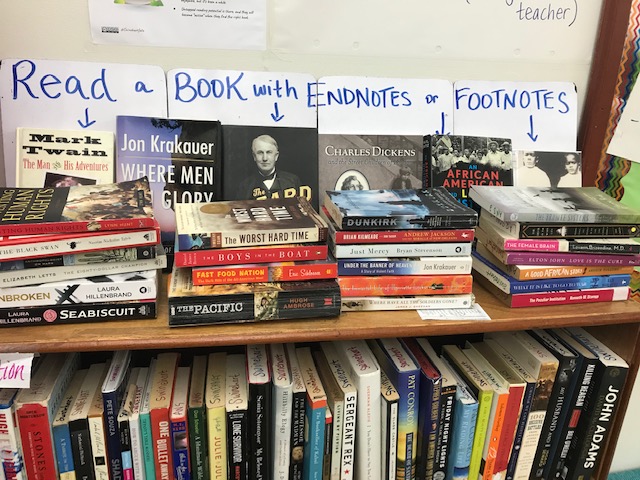

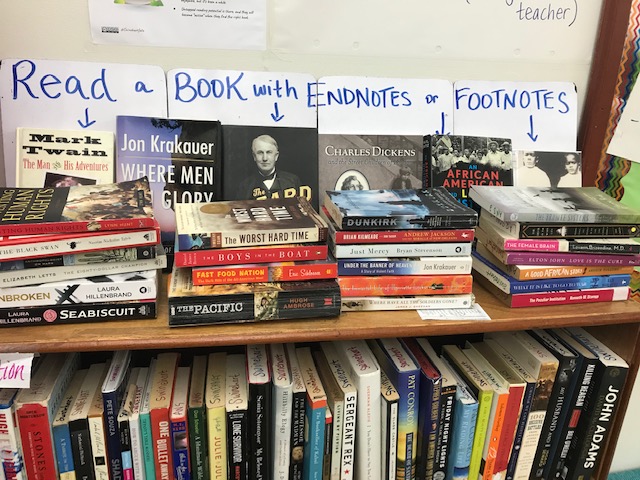

Right now, my AP Lang class is starting a research project. One of their sources needs to be a book with either endnotes or footnotes, so I’ve collected many of my classroom library books that meet that requirement and put them on display.

This display changes about every week or so, sometime with deliberate purpose like this one, and other times it’s just whatever comes to mind. Some recent displays have been around the topics of time travel, aviation, The Great Depression, and sports. Anything goes when it comes to displaying a collection of books.

Another way of displaying and organizing books is by what is popular with students, what the teacher is currently reading, and what’s been book talked in the last day or so.

These are all examples of rotating book displays, and they rotate between every other day, and every couple of weeks. It’s a matter of doing what makes sense for the type of display it is, and what the current needs of the classes are.

So once the books are organized and on display, students actually start to look at them! It’s a miracle, and a wonderful feeling when they get interested and excited when they haven’t been in the past.

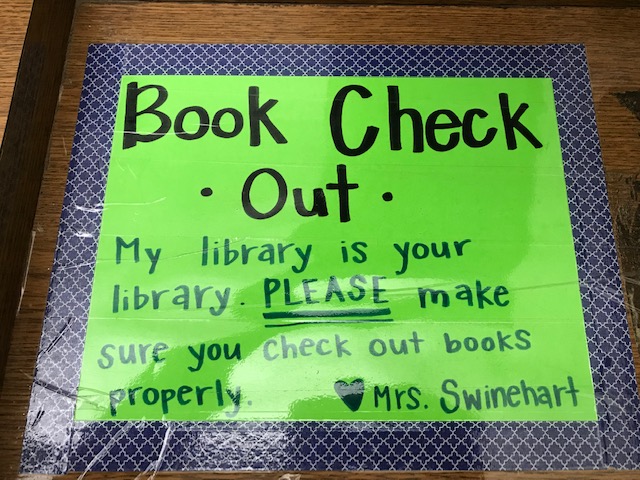

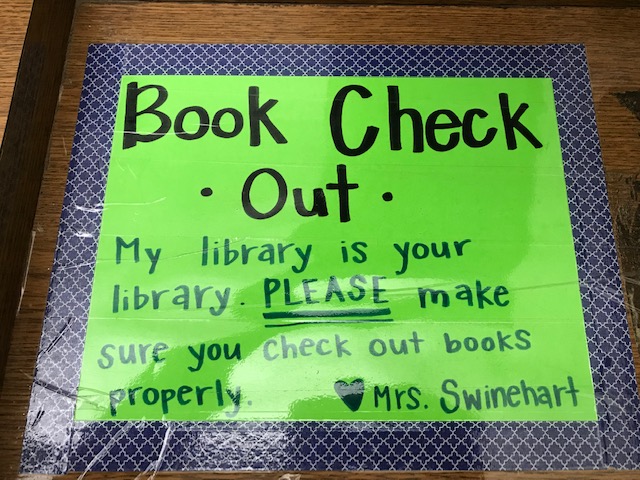

At that point, a check out and return system becomes key.

Mine is old-fashioned and easy to navigate. It’s a spiral bound notebook and a pen. Pretty simple.

Just because it’s low-tech doesn’t mean it doesn’t work. Quite the opposite. Students know to check out books and put them in the return basket when they are done. Sometimes they cross out the original entry of their returned book, but mostly all they have to do is put the book in the return basket and I’ll find their name and cross it off and then re-shelve the book.

The return basket is right next to the check out notebook and this sign which reminds students that the honor system is what makes this whole thing work.

The classroom libraries in our hall are open to all of our students, so often students from other classes wander in to my classroom looking for books. The system is the same for them as it is for the students I currently have in my classes. All of the students at our school are our students; all of the students have access to all of our classroom libraries.

If some students have books out for a long time, and we don’t see those students on the regular because they aren’t in our own classes, we rely on each other to ask those students about those titles, which means we often get books returned promptly with that simple system. Our department has a shared google doc and we list the students’ names and titles that are checked out, so we all have that information at our fingertips.

Our organizational and check-out systems are thoughtful and simple, and can be adopted by almost anyone. There may be other better, different, or more complicated ideas and systems out there that work for people, but I wanted to share ours because of its simplicity and effectiveness.

How do you organize your classroom library, and what philosophical beliefs to you hold that are behind these practices? I’d love to read your thoughts in the comments.

Julie has been teaching secondary language arts for more than twenty years, spending the first fifteen in rural Central Oregon, four in Amman, Jordan, and the most recent school years in Managua, Nicaragua.

Follow her on twitter @SwinehartJulie

Kittle is right: “The language we use to invite talk begins with the questions we ask.” Because coaches’ learning centers around building rapport, trust, and reflective capacity, and because we are (or at least should be!) the most coached in a building, we’re uniquely centered to model questioning and listening and to coach on it.

Kittle is right: “The language we use to invite talk begins with the questions we ask.” Because coaches’ learning centers around building rapport, trust, and reflective capacity, and because we are (or at least should be!) the most coached in a building, we’re uniquely centered to model questioning and listening and to coach on it.

might be able to help identify titles. If that is not yet part of the culture, there are lots of places you might go to look for ideas. You can visit websites like

might be able to help identify titles. If that is not yet part of the culture, there are lots of places you might go to look for ideas. You can visit websites like

Now that you have your Book Club Kits organized, I strongly encourage you to check out the book

Now that you have your Book Club Kits organized, I strongly encourage you to check out the book