As I read through Cyndi Faircloth’s post a few weeks back on Applying Essential Questions in Workshop, it got me thinking about the role of essential questions in my own classroom. As Cyndi said, I needed to do more. Using the essential question to choose mentor texts, guide quick writes, and frame discussion, we had done. I also encourage students to see the essential question as something answered by each and every text we encounter.

But this was about doing more. This was about students answering the question for

themselves; students lending their unique voices as “texts.” I was going to need to look at this from another angle.

My AP Language and Composition students recently finished a unit on community. They worked in and around the essential question, “What is the relationship of the individual to the community?” Through the study of a variety of essays, including everything from Henry David Thoreau’s “Where I Lived and What I Lived For,” to Scott Brown’s “Facebook Friendonomics,” to student selected current event articles, I watched my scholars analyze text to connect author’s purpose with rhetorical strategies. However, beyond that, I was blessed to be able to witness a conceptual development in these classes too.

worked in and around the essential question, “What is the relationship of the individual to the community?” Through the study of a variety of essays, including everything from Henry David Thoreau’s “Where I Lived and What I Lived For,” to Scott Brown’s “Facebook Friendonomics,” to student selected current event articles, I watched my scholars analyze text to connect author’s purpose with rhetorical strategies. However, beyond that, I was blessed to be able to witness a conceptual development in these classes too.

Students seemed genuinely surprised when they considered just how many communities they are a part of: geographical, family, faith, school, sports, friend, experiential. But when they started to consider their roles within those communities and words like responsibility, conformity, and balance began to dominate class discussion, I knew they were really on to something.

Students spoke of the dangers of conformity alongside the necessity for it. They explored the freedom found in chosen communities and the often unwelcome responsibilities to those communities we fall into by default. I saw them wrestle with the concept that communities rise and fall based on the actions and inactions of their members, and then saw evidence in more than one journal entry of the very real concern students have for their own part in that equation.

As these kids get ready to head off to a world beyond the insulated suburban existence most of them have known all their lives, they know many of their foundational communities will be changing. For some, this change can’t come soon enough. For others, I think it will be a rude awakening. And still others, a chance to move toward the authentic selves that they so desperately need to discover.

As these kids get ready to head off to a world beyond the insulated suburban existence most of them have known all their lives, they know many of their foundational communities will be changing. For some, this change can’t come soon enough. For others, I think it will be a rude awakening. And still others, a chance to move toward the authentic selves that they so desperately need to discover.

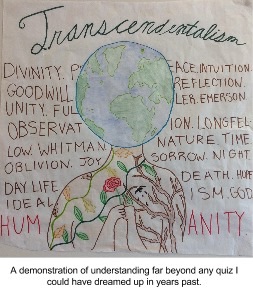

To bring this unit to a close, I wanted to harness all the unique inquiry that we had experienced. To do so, I borrowed from my American Literature class. Throughout this year, my sophomores have started each unit by doing a bit of research on literary movements in American Literature (somewhat of a snoozefest to many). I wanted them to have some contextual understanding of the mentor pieces we would study, and so they gathered information on historical events responsible for the movement, major themes of works at the time, elements of style popular during the period, connections to music and art, and famous authors working within that movement.

Students gathered and compared their research findings in small groups and then were charged with symbolically representing their research on poster sized paper. For the imaginative qualities of Romanticism, we saw Sponge Bob. The Transcendentalist faces of Emerson and Thoreau became flowers in a pot, watered by Walt Whitman. Mark Twain held up a mirror to a map of the American South. In  short, students captured the movements and we hung up the evidence to remind us of the context of what we were exploring.

short, students captured the movements and we hung up the evidence to remind us of the context of what we were exploring.

And so, for my AP Language students, I chose to end their unit on community by bringing

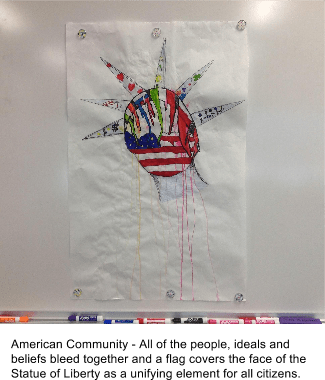

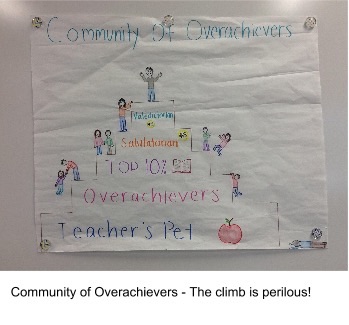

them together in small groups as well, to choose a specific community and illustrate an answer to the unit essential question. I figured if they answered the question without a specific community in mind, we’d get a lot of generic posters with people holding hands around the world – thank you, Google.

Instead, they had to choose specific communities to show their understanding of the complexity of the essential question and then supply textual evidence from the mentor texts we explored in order to support those symbolic meanings.

Students shared some phenomenal work and I was impressed not only with the depth of their thinking, but the synthesis of texts this activity produced. And, because my own artistic development was apparently arrested in the second grade, it was such fun to see some of my visually gifted kids shine through the use of a new medium.

Students shared some phenomenal work and I was impressed not only with the depth of their thinking, but the synthesis of texts this activity produced. And, because my own artistic development was apparently arrested in the second grade, it was such fun to see some of my visually gifted kids shine through the use of a new medium.

Zoey and Alyssa, who created the Statue of Liberty visual said the exercise allowed them to express their “artistic qualities – which is many times put on the back burner in AP courses.”

Creative expression of understanding put on the back burner? Shame on us.

And I know for a fact that AP classes aren’t the only place to suffer a similar fate. If we are going to do more with essential questions, we need to not only have students to be directly involved in answering them, but also give our kids more voice in the demonstration of their learning.

Ultimately, it was an assessment that combined creativity, common core standards, direct connection to the unit essential question, analysis, entertainment, synthesis, and genuine student enthusiasm. Not bad for mid-February in the frozen North.

How do you use essential questions to effectively deepen critical thinking? Please share your comments.

ow characters and plot lines develop and how they mirror their lives. She challenges students to consume pages, develop stamina, and grow in fluency. She gives them opportunities to read more and read harder because she knows the value of reading in building confidence and competency. She introduces different genres, authors, themes. She surrounds them with shelves weighed down by high-interest books and gives them time to read in class. To this teacher, it is not about the book — or the six books of lofty literary merit — it is about the reader. Readers who read 12 books in a year instead of just six. This teacher knows if she makes a reader she can make a life. And the skills gained through reading extensively transfer to their writing and permeate like energetic friends into the reading they must do in other classes.

ow characters and plot lines develop and how they mirror their lives. She challenges students to consume pages, develop stamina, and grow in fluency. She gives them opportunities to read more and read harder because she knows the value of reading in building confidence and competency. She introduces different genres, authors, themes. She surrounds them with shelves weighed down by high-interest books and gives them time to read in class. To this teacher, it is not about the book — or the six books of lofty literary merit — it is about the reader. Readers who read 12 books in a year instead of just six. This teacher knows if she makes a reader she can make a life. And the skills gained through reading extensively transfer to their writing and permeate like energetic friends into the reading they must do in other classes.