We all feel it, don’t we? That time of the year when teaching gets tough: skies get darker, holidays come looming, and students look out windows more than they look to learn. I have 2.5 days until the break, and, like you, I am ready.

This is the time of year I start to question myself. Have I taught the way my students need me to teach? Have I made them feel special, valued, a part of our learning community? Have they learned anything?

These were my musings last week when I got a special gift in my inbox: three photos of a former student’s fingernails.

With this message:

This is totally random, but I thought you might like to know that aside from all of the English, reading and writing skills that you taught me. . .our end of the year project (the How-To), has actually helped me in real life! If you remember, I did my project over biting nails because I desperately wanted to stop. After that project, it was so easy to, and I haven’t bitten them since the end of the year in your class 6 months ago! I’ve attached some pictures… Like I said, this is super random & weird, but if you’ve ever wanted proof of that project actually working, here is my successful end product.

Does this count as hard data?

Yesterday I answered questions about student data in a phone interview. One question went something like this: If a cynic questions your methods, what do you do to win her over?

The exchange left me unsettled. I said I would show the cynic student work and let her read students’ self-reflections on their learning. I spoke about how the data I care about is the qualitative type that comes from my observations, conferences, and interactions with students. I value process over product.

I think my response fell flat with my interviewer. Maybe she wanted numbers. What would she think of Micaela’s nails as proof of my instructional methods?

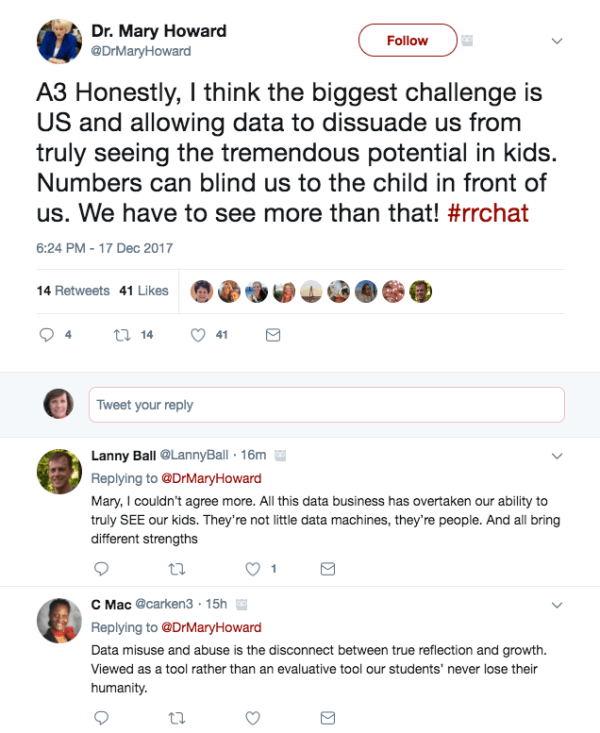

Later in the day I twittered upon these tweets:

The whole thread rings true. And I’ll add this: Numbers mean nothing if we do not add value to a child’s life and help her learn to thrive, achieve, and find herself within it.

I’ll be honest: I thought Micaela chose an easy topic last spring as her final writing piece: a multi-genre project that was more than a how-to but a comprehensive argument for or against an issue; I didn’t think she could write enough about breaking her habit. But I got out of her way, and she composed a multi-layered piece about the shame and the struggle and her desperate desire to leave her nails alone.

I’ll go on break this Thursday. But when I get back to work in 2018, I’ll remember Micaela. What do my students need beyond my ELA curriculum? What motivates their thinking? What will my students choose to do this spring if I remember to get out of their way?

Amy Rasmussen shares a classroom with juniors and seniors at Lewisville High School in North TX where she learns as much from them as they ever do from her. She was once a nail-biter herself. Writing a paper about her habit at 16 might have helped her kick it a lot sooner. She was 21. Amy wishes you a joyful holiday and a Happy New Year, and sincerely thanks you for following and sharing Three Teachers Talk.

am teaching children. Teenagers, yes, but still kids who are not intentionally trying to drive me to an early retirement. They just don’t feel the passion for books, reading, writing, and language like I do — yet. Many have played the game of school so long they don’t see that they could actually like it if they’d play a different way.

am teaching children. Teenagers, yes, but still kids who are not intentionally trying to drive me to an early retirement. They just don’t feel the passion for books, reading, writing, and language like I do — yet. Many have played the game of school so long they don’t see that they could actually like it if they’d play a different way.

I really don’t think there’s anything more invigorating than learning with other teachers, and this week, I’m doing just that.

I really don’t think there’s anything more invigorating than learning with other teachers, and this week, I’m doing just that.

uniqueness of each community of learners, and the ever-changing nature of our global landscape, we must continually rethink, revise, and renew our practice. Otherwise — to paraphrase Dewey — we rob “today’s students of the tomorrow today’s students deserve” (10).

uniqueness of each community of learners, and the ever-changing nature of our global landscape, we must continually rethink, revise, and renew our practice. Otherwise — to paraphrase Dewey — we rob “today’s students of the tomorrow today’s students deserve” (10).

rules to keep the wheels turning. There was no student choice, just multiple choice. No discussions, just lectures. No collaboration, just eyes tracking the teacher.

rules to keep the wheels turning. There was no student choice, just multiple choice. No discussions, just lectures. No collaboration, just eyes tracking the teacher.