Before a recent literacy conference in my state, an educator I follow, Lois Marshall Barker (@Lit_Bark), tweeted a popular phrase from Grenada, “Give Jack he jacket.” She was reminding everyone to cite their sources in presentations, and I fell in love with the phrase. Though ethical and academic standards for copyright, plagiarism, and citation have been a part of our literary world for centuries, the instantaneous access to seemingly infinite resources and information of the internet generation has changed the conversation. While formatting those citations in my youth required purchasing the latest edition of the required style guide, now students can easily use digital sites or add-ons to do the formatting in just a click. What have become the more crucial skills to teach are discerning the credibility of the sources that are being cited and avoiding plagiarizing the ideas of others.

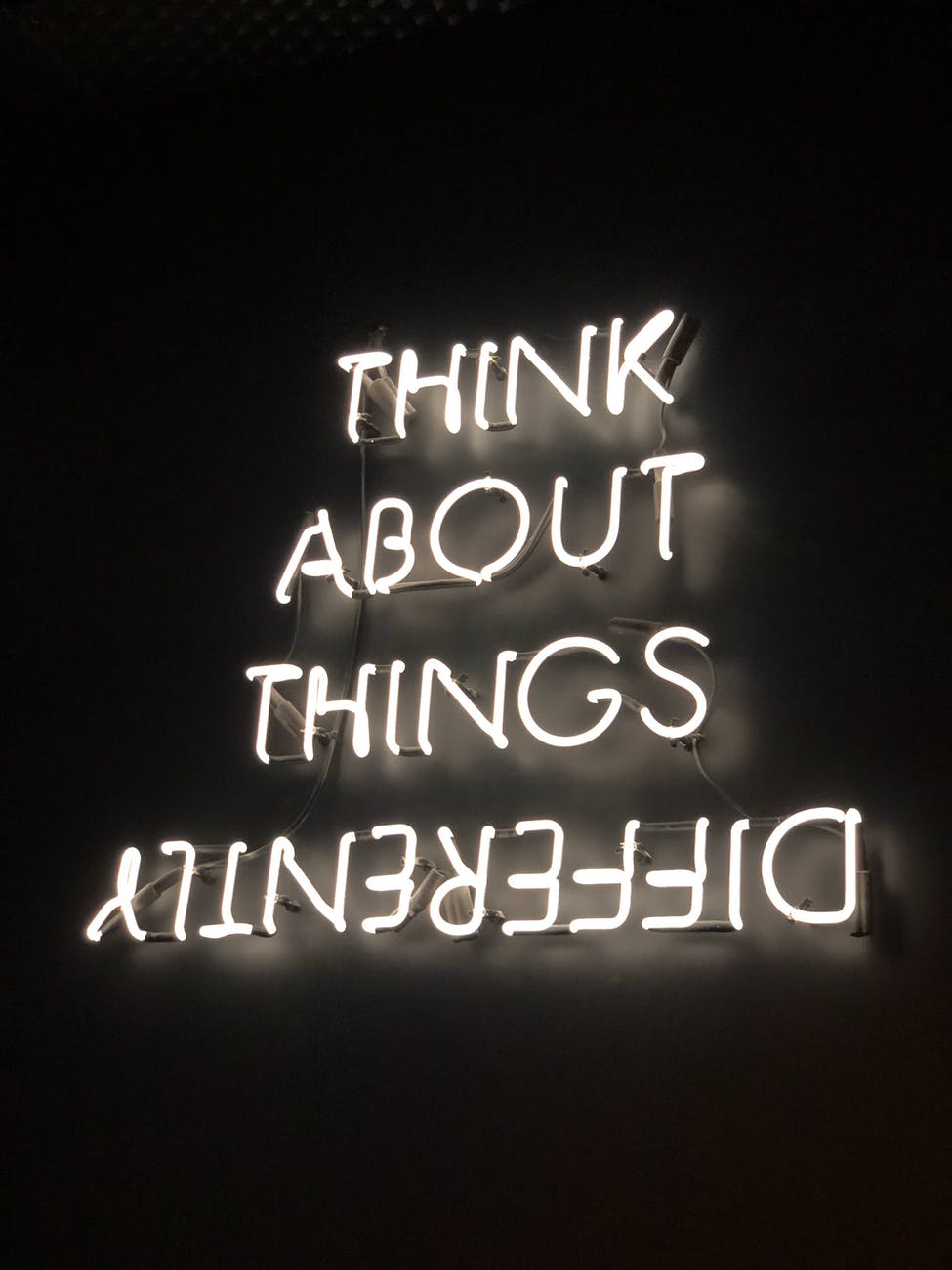

Teachers and librarians are teaching critical inquiry lessons to help students learn to evaluate the deluge of information available to them in simple browser searches. A quick Google search will yield many excellent #fakenews lessons. Both Common Core and other state standards include evaluating sources, avoiding plagiarism, and citing properly. While many educators consider these to be College and Career Readiness standards, given the meteoric rise of social media as a news source, these standards actually deserve to be labeled “the most essential standards”.

As “the most essential standards”, the ideas of evaluating a source or author and then giving accurate credit (Give Jack he jacket) must be taught explicitly and modeled with every different piece of text that students are invited to interact with in the classroom. Teaching these standards only when students are doing a research project or paper isolates or compartmentalizes these fundamental skills when they are truly skills that all literate adults must master in order to navigate the inundation of digital information that is at our fingertips or in our feeds.

With the open access to information that technology provides, plagiarism now can be a simple act of “cut and paste”, so understanding the ethical reasons for avoiding plagiarism and giving credit to authors must be an on-going, face-to-face, teacher-student conversation. Writing conferences provide teachers with many quick opportunities to check-in with students throughout the writing process, and these conversations can grow ethical student writers in deeper ways than simply paying for an expensive on-line plagiarism checker and rarely talking about or modeling how to avoid plagiarism. If only for this one reason, secondary language arts teachers have to find creative ways to make a routine of writing conferences.

As a parent of teens, I have had many conversations about “right and wrong” with my own children who have grown up in a very different world (technologically speaking) than I did just 25 years ago. Heated debates about finding and downloading “free” movies and books on-line has helped me understand how crucial (and frequent) these discussions must be in classrooms, too. The teen default response,“Everyone else does it”, really does seem to apply in this instance, but I firmly believe that teaching “right from wrong” does work when done repeatedly, systematically, and relevantly. And, I think these “most essential standards” must be taught by one writer to another writer and not simply relegated to a digital algorithm that “checks” for less-than-ethical choices.

Please share (in the comments below) your best lessons and resources for teaching how and why to avoid plagiarism.

A few resources:

Commonsense Media CultofPedagogy AMLElesson

his one. I loved it,” she suggested as she handed him Kwame Alexander’s Crossover. A few days later, the student shyly asked the teacher for another book just like that one. And the teacher found one and then another for him. Because this teacher read young adult literature, she could bring herself into the classroom in the same way Julie Swinehart did in

his one. I loved it,” she suggested as she handed him Kwame Alexander’s Crossover. A few days later, the student shyly asked the teacher for another book just like that one. And the teacher found one and then another for him. Because this teacher read young adult literature, she could bring herself into the classroom in the same way Julie Swinehart did in