My two-year-old grandson is a master manipulator–or maybe he’s just brilliant.

Over the weekend, his mom and dad took a little anniversary trip, so Papa and I tended Indy and his baby brother. More than once, when we needed/wanted/pleaded with Indy to do a certain thing, he ran to the bookcase in our room, pulled out a book–or four or seven–and sat down to read. “Shh. Quiet,” he’d say, patting the space on the floor next to him in a commanding invitation to sit beside him.

What else is a grandparent to do but stop and read with the little man?

We all know the benefits of reading to young children. (Google gives “about 921,000,000 results” for the question.) We also know that somewhere along the way, many children, maybe especially adolescents, come to not like reading.

Most of us face two challenges:

How do I get students to read when they just don’t want to?

How do I get students to read when they just don’t seem good at it?

I used to think it was all about the books. You know, I’d pack the shelves in my classroom library with the most colorful, interesting, inclusive, newly published, award-winning books; I’d talk about these books A LOT, doing my best to match books with student interests. I’d do All The Things.

And, yeah, many students came to like our dedicated daily reading time. Some of them even came to like the books they read. Many of them claimed to have read more than they ever had before. I’m just not super sure how many students came to really like reading.

Maybe that’s okay.

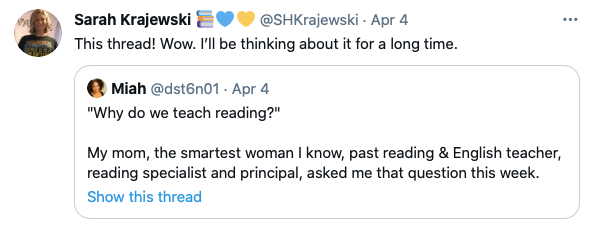

The other day I saw this tweet by Sarah, a friend and contributor to this blog, and I quickly read the whole of the thread posted by Miah on April 4. It’s a beautifully constructed and compelling argument and well worth your time to read in full. Like Sarah, “I’ll be thinking about it for a long time.”

Today, I’m thinking about it here in relation to my tiny grandson and the reader he may be when he’s 10, 14, 17, or 37.

Miah lists reasons we teach reading: “We teach reading for. . .security. . .self-advocacy. . .freedom. . .economic security. . .social justice. . .evolution. . .social advancement. . .liberty in the highest sense of the word.”

and includes this sage advice–

I think we know what “the noise” is, even beyond how Miah describes it. There’s noise in so many aspects of our teaching lives. And sometimes, nay often, it is hard to ignore. Yet you and I both know we must.

And I think one way to do it is to position liberty: We teach reading for liberty, but we also teach reading through liberty.

If you’re nerdy like me, maybe you look up “liberty” in the dictionary. Merriam-Webster offers a whole list of definitions: “The quality or state of being free” and all the context descriptors–all but speak to the importance of student choice when it comes to reading in a high school English class. Thus, a robust classroom library and all the things.

Then, there’s this definition: “a right or immunity enjoyed by prescription or by grant : PRIVILEGE”

And there it is–the word privilege making me think again.

In context of my teaching practice, who has the liberty to talk, ask questions, move about the room, take risks, choose texts, shape plans, assess learning? What’s privileged, where, and when?

And, yes, I know–if you’ve read this blog for awhile now, I am most likely preaching to the choir.

But even if we “get it,” even if we try it, even if we’re tired of trying or tired of this pandemic, even if we cannot handle one more decibel of noise–if we believe in empowering students with the skills they need to capitalize on the liberty life affords them–or liberate themselves so they have more–we keep thinking and reflecting, and we keep doing the things that help young people have experiences with reading that make them want to read.

Try This “Conversation Starter” (I read it recently in the Morning Brew, an online newsletter I read pretty much every day.)

If your bookshelf could only have five books, what would they be?

You can learn a lot about an individual–positive, negative, and otherwise–depending on the books they choose, or if they don’t make any choices at all.

Amy Rasmussen is a lover of words, color, and living things–like plants, art frogs, and grandkids. She lives in North Texas and escapes for long periods of time on the country roads near her home. She writes (mostly in her notebook) to see and feel and think in new ways, and when it comes to publishing anything publicly, her phobia of heights doesn’t seem half bad. Amy has a book about authentic literacy practices she’s co-written with Billy Eastman due for publication this fall. She’s both excited and terrified. Follow her @amyrass –maybe she’ll get a little more active on social media.