You tell me you know

what it’s like to be

a teacher in a pandemic.

Yes, you’ve had zoom meetings, too!

You worked from home as well, juggling

kids, work, health, social isolation.

You were also scared, but somehow

somewhat relieved because of the freedom

from hectic schedules.

You, too, weathered the pandemic.

But were you forced back

to in-person work while the government

officials declared that you were essential

not for educating children, but to get the economy

back “up and running”?

Were you forced to do your job twice over

in-person and online at the same time?

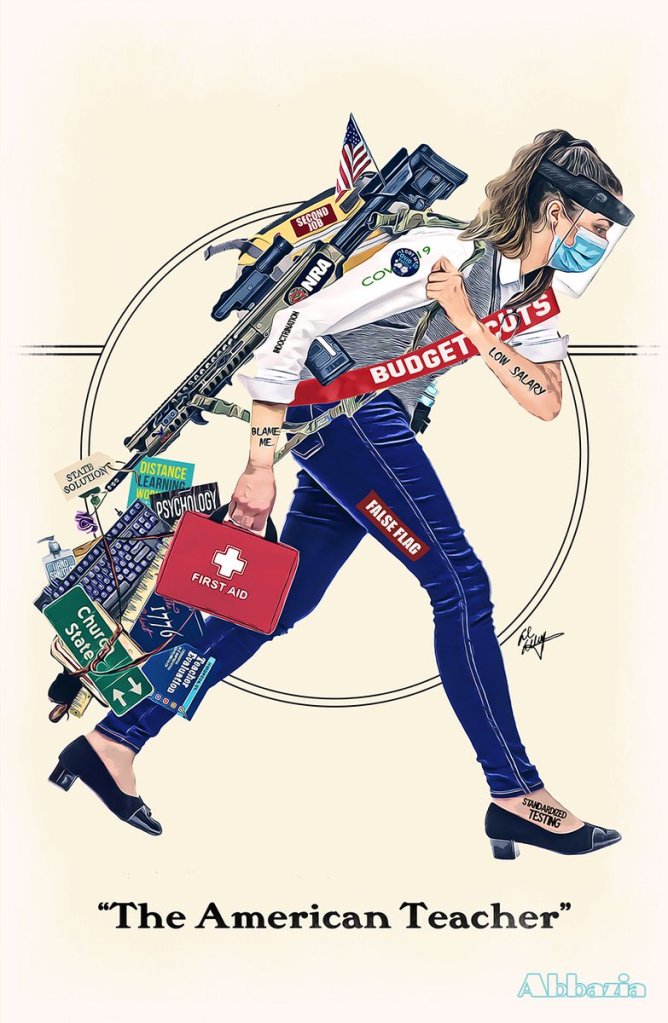

Were you also given new duties of nurse,

custodian, and therapist for the inevitable trauma?

Were you constantly gaslit, told to “smile,

the kids need to see that everything is okay,”

yet you went home and often cried because

no one was assuring you?

Were you then told that despite

your hard work and grueling year,

“the students are behind” and

you must find a way to “catch them up”?

You tell me you know

what it’s like to be

a teacher in a pandemic,

and you may have lived through

this historical event at the same time

as us, but

you will never truly understand

what it has been like

to be an educator in this time.

One of my favorite Quick Write lessons of all time was when I showed my students this video of Darius Simpson and Scout Bostley performing “Lost Voices,” and then we responded with our own poems, starting with the line “You tell me you know what it’s like to be…” From there, students could choose any identity they had that they felt people often acted like they understood or could relate with, but it was too deeply a personal experience that those outside of that identity could never understand. This idea came from Penny Kittle and Kelly Gallagher’s 180 Days in the Narrative section where they provided all sorts of mentor texts for “swimming in memoirs” to encourage students to address their own story from lots of angles.

When I did this lesson with my students in my second year, they soared. I got quick writes that started with “You tell me you know what it’s like to be autistic,” “You tell me you know what it’s like to be an assault victim,” and “You tell me you know what it’s like to be an immigrant.” Each story, each window into those students’ lives were so powerful. I often did not know what it was like to be what my students were writing about, but their willingness to be vulnerable in their writing helped me see from their eyes and understand just a little more.

As I recover from this year of teaching in a pandemic, my mind wandered back to that activity, and I began writing the beginnings of the poem above. As I mentioned in my previous post, I struggle with finding time/space/ideas/willingness to write. I keep having to learn that it often only takes a strong mentor text and I am off to scribble in a notebook. This remembering will play a huge role in my teaching this coming year. I am also having to constantly re-learn/remind myself how powerful a tool writing is for processing things. It has been an almost impossible year for many teachers, including me. It is only the beginning of summer, but I have had all sorts of reflections and emotions surface. I hope, if you want to get into more writing as well, that you will take time to soak in the words of these poets and write your own “You tell me you know what it’s like to be” poem. Maybe it’ll help you process the emotions and experiences of your year, too.

If you do write using these ideas, please share in the comments or tweet it tagging @3TeachersTalk.

Rebecca Riggs is a writer (or tricking herself into being one the same way she does her students- by just declaring it so). She is currently reading The Girl Who Smiled Beads: A Story of War and What Comes After by Clemantine Wamariya and Elizabeth Weil. Her current obsession is trying out new cookie recipes and working hard to not fill up her entire schedule so she can actually rest this summer. You can connect with her on Twitter @rebeccalriggs or Instagram @riggsreaders.

York in the 1980s, a time when vagrants and panhandlers were as common a sight in the city as kids on bikes or moms with strollers. The nation was enjoying an economic boom, and on Wall Street new millionaires were minted every day. But the flip side was a widening gap between the rich and the poor, and nowhere was this more evident than on the streets of New York City. Whatever wealth was supposed to trickle down to the middle class did not come close to reaching the city’s poorest, most desperate people, and for many of them the only recourse was living on the streets. After a while you got used to the sight of them–hard, gaunt men and sad, haunted women, wearing rags, camped on corners, sleeping on grates, asking for change. It is tough to imagine anyone could see them and not feel deeply moved by their plight. Yet they were just so prevalent that most people made an almost subconscious decision to simply look the other way–to, basically, ignore them. The problem seemed so vast, so endemic, that stopping to help a single panhandler could feel all but pointless. And so we swept past them every day, great waves of us going on with our lives and accepting that there was nothing we could really do to help.

York in the 1980s, a time when vagrants and panhandlers were as common a sight in the city as kids on bikes or moms with strollers. The nation was enjoying an economic boom, and on Wall Street new millionaires were minted every day. But the flip side was a widening gap between the rich and the poor, and nowhere was this more evident than on the streets of New York City. Whatever wealth was supposed to trickle down to the middle class did not come close to reaching the city’s poorest, most desperate people, and for many of them the only recourse was living on the streets. After a while you got used to the sight of them–hard, gaunt men and sad, haunted women, wearing rags, camped on corners, sleeping on grates, asking for change. It is tough to imagine anyone could see them and not feel deeply moved by their plight. Yet they were just so prevalent that most people made an almost subconscious decision to simply look the other way–to, basically, ignore them. The problem seemed so vast, so endemic, that stopping to help a single panhandler could feel all but pointless. And so we swept past them every day, great waves of us going on with our lives and accepting that there was nothing we could really do to help.