Usually I read about four books at a time. This makes for a mess on the bedside table, the coffee table, the kitchen table. I rarely use bookmarks, which is a shame because I have quite a lovely collection.

Usually I read about four books at a time. This makes for a mess on the bedside table, the coffee table, the kitchen table. I rarely use bookmarks, which is a shame because I have quite a lovely collection.

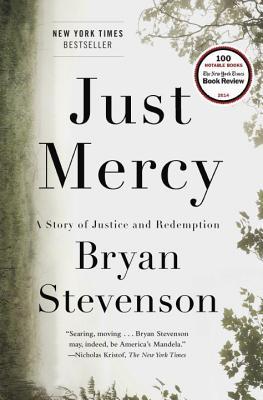

I end up leaving books split open and sound asleep right where I left them –sometimes just so I can remember the parts I know I want to use in class. I refuse to read on until I capture the sentence or passage that gives me pause. Such is the case with my new now bent-spine-copy of Just Mercy, a Story of Justice and Redemption by Bryan Stevenson. I’ve been stuck on page 18.

Here’s a portion of the passage I will use with my AP Lang students. You will, of course, find the rest of it when you buy the book, or here.

When I first went to death row in December 1983, America was in the early stages of a radical transformation that would turn us into an unprecedentedly harsh and punitive nation and result in mass imprisonment that has no historical parallel. Today we have the highest rate of incarceration in the world. The prison population has increased from 300,000 people in the early 1970s to 2.3 million people today. There are nearly six million people on probation or on parole. One in every fifteen people born in the United States in 2001 is expected to go to jail or prison: one in every three black males babies born in this century is expected to be incarcerated.

We have shot, hanged, gassed, electrocuted, and lethally injected hundreds of people to carry out legally sanctioned executions. Thousands more await their execution on death row. Some states have no minimum age for prosecuting children as adults; we’ve sent a quarter million kids to adult jails and prisons to serve long prison terms, some under the age of twelve. For years, we’ve been the only country in the world that condemns children to life imprisonment without parole; nearly three thousand juveniles have been sentenced to die in prison.

…

We also make terrible mistakes. Scores of innocent people have been exonerated after being sentenced to death and nearly executed . Hundreds more have been released after being proved innocent of noncapital crimes through DNA testing. Presumptions of guild, poverty, racial bias, and a host of other social, structural, and political dynamics have created a system that is defined by error, a system in which thousands of innocent people now suffer in prison.

…..

We are all implicated when we allow other people to be mistreated. An absence of compassion can corrupt the decency of a community, a state, a nation. Fear and anger can make us vindictive and abusive, unjust and unfair, until we all suffer from the absence of mercy and we condemn ourselves as much as we victimize others. The closer we get to mass incarceration and extreme levels of punishment, the more I believe it’s necessary to recognize that we all need mercy, we all need justice, and — perhaps — we all need some measure of unmerited grace.

Before we ever read the text, and I did pull much more of it than I’ve posted here, we’ll spark our thinking with an image like this, posted at The Sentencing Project, and then write our initial responses in our writer’s notebooks:

Next, we will TALK. I know my students will want to share what they think about this graphic. Many will identify personally with it because they know a family member or a friend who’s served prison time.

When I introduce them to Stevenson’s text, I’ll give them a purpose for reading — besides just comprehending the message (identifying the purpose is a breeze since he tells us the reason he writes the book) — I want my students to notice the structure, the progression between ideas, the repetition and patterns they will see in the language. All the clues that build the tone.

I will ask them to mark the text, noting their thinking about these things. Without a purpose for reading, too many of my students struggle with the stamina they need to make it through even a page when I ask them to read critically.

Next, we will TALK. Talking will help some students understand what they read. It will help other students clarify their understanding. Some students will have noted what I asked them to notice as they read. I will rely on them to help the others — skill level is just one way my students are diverse.

I will also hand them a stack of questions that prepare them to write. They will read something like this:

What do you know about the writer based on what he writes?

What is the Stevenson’s purpose? Why does he come out and tell us so plainly?

What are the facts in this piece? What are opinions? How do you know?

What do you notice about the structure, any patterns, repetition? What do they do for the message?

How does Stevenson move between ideas?

And then we will write. Maybe I’ll give a prompt like this: Based on the text, and our discussion, is Stevenson’s opening argument effective, why or why not? Maybe I’ll ask students to come up with their own analytical-style question to respond to. (I like this idea a lot.) [see Talk Read Talk Write]

That’s probably enough for one class period, but my mind is still stirring:

- What if I ask students to problematize the issue? Who are the stakeholders? Think all the way around the issue. Why do they care? Why do we care? What kinds of questions do we have about the claims Stevenson makes? What kinds of evidence do we need to convince us they are valid? How and when could anything regarding this issue change?

- What if I ask students to identify just one of Stevenson’s claims and then research it? I assume the author provides support throughout the book. I’ll know when I keep reading. But what if students did a bit of research and then collaborated on substantiating Stevenson’s claims. Collaborative writing can be a powerful learning experience.

- What if I ask students to brainstorm other issues Stevenson’s text suggests? We could probably create a pretty elaborate bubble map of ideas. These could lead to student choice in research topics.

What do you think? Any other ideas?

©Amy Rasmussen, 2011 – 2015