The comment on my post said: “I have been book talking, conferring, doing mini lessons, and incorporated the workshop approach, yet my AP Literature scores went down dramatically. Now what???”

My initial response sounded something very Donalyn Miller-like when she said to me a few years ago: “It’s not all about the test, is it?” At the time, I thought it was, and her remark stung.

Now, I know better.

The letter below is how I responded to this very dedicated teacher who is doing her best to help her students be successful, not just on an exam, but in life. I can feel her earnest desires in first this comment and then in an email message. Chin up, my new friend, you are doing right by students because you are taking them beyond test prep and into adult learning. I applaud you.

Hello,

I feel your pain. I thought my students would do much better than they did, but then again — I think that every year.

Right after exam scores were released, I got a message from my colleague: “My AP Lit scores are the worst they have ever been.” Although she is a good teacher, and I trust her ability to educate teenagers, she is not a workshop teacher. She allows little choice, and students only do the kind of writing in her class that they will do on the AP exam. My advice to her: Choice Reading.

Now, I hear from you, and you say your scores plummeted. You have been doing elements of workshop, and my advice is the same but more: More choice reading.

While I guess my voice is emerging as ‘an expert’ — probably because I post and talk about this so much, I must tell you: I cannot base my expertise with readers/writers workshop in advanced classes on qualifying exam scores. I can only base it on my research on reading and on the personal experiences I’ve had with moving my students as readers and writers and preparing them for the kinds of reading and writing they will have to do in college. My evidence is the growth of my students, and that cannot always be measure by an exam — it rarely can.

I am used to teaching at a high poverty school that embraces the College Board’s Open Enrollment with no prerequisites. Pretty much any student who says she wants to take an AP class can — and does. I agree that every child should have the opportunity to take advanced classes, but I also think we do them a disservice by allowing them to attend a class when they do not have either 1) the reading and writing skills to engage in the learning, or 2) they do not have the work ethic to push themselves into engaging in the learning. Skill and will sit on that scale so precariously.

I know you know this already: the AP exam represents one day of the student learning journey for that whole year. Students might be hot or cold or sitting in a luke-warm bath on exam day. I know that the majority of my students enter that room and take that exam as confident writers because I’ve seen them move from sometimes a -1 to a 5, or even a 6, on the writing rubric. But I cannot get non-readers to read the complex texts they must in order to get at least 50% correct on the multiple choice part of that exam. Of course, I cannot be certain because the score report does not show the break down between the essays and the multiple choice, but I know in my gut (and from what I’ve seen on mock tests), that my students who do poorly on the exam do so because they bomb the reading portion.

That is the basis of where I am coming from when I share with you what I think. It’s hard not to compare my scores with my colleagues’, but I have to remember: it’s the luck of the draw which students end up in which sections with which teacher. It is rarely a fair balance of students’ abilities prior to them ever walking in my door.

Please know that I trust you are a fine educator. If you were not, you would not be seeking help to improve. And I will be honest, you have more years experience teaching AP English than I do.

I am going into my sixth year teaching AP, but I can tell you, I had disengaged kids, and I never moved more than a few readers and writers in those first couple of years. I made the choices, and most of them faked their way through the classic texts I selected. I just re-read the journal article “Not Reading: the 800-pound Mockingbird in the Classroom” by William J. Broz, and I wonder why I allowed those students to pass my English class. Broz says, “Not reading should mean that those students fail the course because they have no assignments to turn in.” I get that now.

Like you, I am a fan of Penny Kittle. For the past two years I have gone to the University of New Hampshire and taken a graduate course that she’s taught. This year she had us study reading theory. It was hard. But I am even more confident that allowing students choice in what they read and what they write is more important that the scores on the AP exam. That thinking takes a little getting used to, especially if you are used to getting high scores. We have to remember that the change in students’ lives, primarily because of their use of technology, has changed their willingness to engage with a book, and often their willingness to even attempt deep thinking, homework, and the like. Mark Prensky and Alan November’s work supports this. Prensky even asserts that students brains may be wired differently. I think I might believe that.

If you have not read the essays of Louis Rosenblatt, especially one titled “The Acid Test for Literature Teaching,” it will reinforce why you’ve tried to model Penny’s pedagogy to begin with — because you ‘get it’. At the end of her essay Rosenblatt asks these questions (the acid test):

Does this practice or approach hinder or foster a sense that literature exists as a form of personally meaningful experience?

Is the pupil’s interaction with the literary work itself the center from which all else radiates?

Is the student being being helped to grow into a relationship of integrity to language and literature?

Is he building a lifetime habit of significant reading?

I say that if we can answer with an honest yes to these questions — how much do our exam scores really matter?

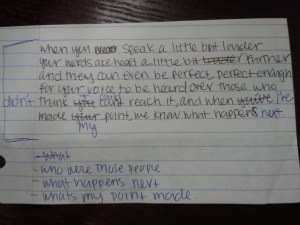

The pedagogy of a readers/writers workshop classroom is in constant motion, continually fluctuating, because we plan and teach and move around the needs of our students. It is hard work because it is differentiation at mach speed. In her class Penny reminded me of a several things that I need to do better. I went through my notebook and made this list. Maybe this will help you, too (in no specific order of importance):

1. The pedagogy in a workshop classroom is 1/3 teacher talk and 2/3 student talk. Am I talking too much, or am I creating opportunities for students to think and debate and discover meaning with one another?

2. “Process is as important, or more important, than our product.” –the theory of Don Graves & Don Murray, UNH. How can I focus more on the process that students undergo to become writers than the writing itself? Do I talk with them as writers, or do I talk with them about their writing?

3. Have students think and analyze their process. “My process changes with genre.” Penny Kittle. If hers does, and mine does, then my students’ should. How do I help them understand why thinking about their process will lead to more accomplished writing?

4. One effective strategy when students say they “do not know”: Define yourself by what you are not. (This is a form of argument, taking on the counterargument from the get-go.)

5. “The hardest part of the writing process is figuring out what to say — when we give kids prompts we take away the hardest part.” Penny Kittle. How can I create a better balance of exposing students to AP essay prompts and free writing and quick writes that generates thinking for essays about topics students want to write about?

6. “Vocabulary from SAT word lists is a waste of time. The SAT draws from a bank of over 5, 000 words, even 25 words a week that you make kids memorize will never get them there.” PK. How can I help students create their own dictionaries, based on the ‘hard words’ they discover in their choice reading books? PK has her students find four a week.

7. Richard Allington’s research says that volume matters for struggling readers. He suggests that they should be reading at least 25 books a year. If that is true for struggling readers, how many books should college-bound students be reading?

8. Multi-tasking has been proven to be a myth. At least 10 minutes of silent reading time per day stills the silence, and a. helps students learn to focus, b. shows students that reading can become a habit.

9. Workshop classrooms are grounded in “Transactional Experience” theory. How do we invite students to have an aesthetic experience with a text?

10. “The success of our teaching is the willingness of kids to engage when we aren’t with them.” PK. How can I set up the learning expectations better so students know the end-goals more clearly? If colleges require 200-600 pages of independent reading a week, and most of my students will go to college, how can I help them engage in the practices that will help them do that now? [This year a group of students practically rebelled. They actually accused me of wasting their time because I refused to do test prep every day.]

11. “No amount of explicit skill instruction can replace the experiences of hearing, reading, learning, and living in a great number of stories.” Ariel Sacks. How can I helps students read like writers so they discover the explicit skills writers use on their own or in small groups? More talk.

12. “Independent reading should deepen thinking for writing.” PK This is where I fell short this year: I didn’t have my students write about their reading. I didn’t make the learning connected enough. I need to have students write informal responses to their reading occasionally in their notebooks, and then they may choose one response to write into a more formal paper. What specific skills can I model as students write their formal responses? Remember Pk’s strategy with quotes across the board and how as students we made connections and then wrote about them. This was synthesis.

13. Mentor texts matter. What additional mentor texts can I have students study prior to major writing tasks? Need maybe 3-5 per genre– or more.

14. With each writing task, students must know the ‘end game.’ The end game is for them to demonstrate their learning. It’s about growth, so even the best writers must show growth, even those who come in my door as A-student readers and writers. How can I score more on process rather than product?

15. There are three types of conferences: 1. monitor the student’s reading life, 2. teach reading strategies, 3. challenge/increase complexity. I do #1 well. How can I improve the other two? If I can focus more on #3, I believe I can move readers into becoming the kind of thinkers they must be on the AP exam.

16. To analyze a text, we must read like writers. How can I teach over comprehension and get students to read as writers regularly? I must model what this means more clearly. This is where regular text studies with short passages matter.

17. “Students should talk regularly about their thinking both before and after writing. They will hear the thinking of others and this will help them extend their own.” PK. How can I work more time for this talk into my daily lesson plans? Scripted questions?

18. “Model your writing. Let students see your struggles.” PK. I need to do this more. Idea from Penny: project two run-on sentences from famous books on the board, i.e. The Goldfinch & ?. Ask: These authors knew better. What was their intent in writing these run-on sentences? This will inspire thinking and talk, then students may write about their thinking. Better than writing “run-on” on their side of their papers.

19. Storyboards can be used to map a chapter, to read it rhetorically, not just for planning a narrative. How can I use storyboards to help students deconstruct a chapter? Then assessment is only looking for evidence of rhetorical reading (how &why).

20. “Put structures in their heads, so they read like writers.” PK. I just need to talk about this a lot more!

21. Ask: “What have you learned about living from this book?” Leads students into reader’s response. This will tie into the human condition and the work as a whole that is needed for the AP exam.

22. Writing conferences. Writers control the conference; they say what they want help with. How can I get students to take ownership of this time to talk with me about their craft? “If you don’t leave a conference wanting to write more, there’s a problem with the feedback.” Don Murray

I hope you find these thoughts and questions helpful. Like you, I am always looking to improve. Every year I hope to open that webpage with exam scores and see all 3, 4, and 5’s. So far, those are a bit spotty, but I admit I am pretty proud of my 2’s. They’ve grown as readers and writers, and I’m okay with having some of my students just College Ready.

I am not one of those people who jumps to the last few pages to read how a book ends before I’ve ever started it. I do not understand those people. At all. I like to savor a good book, take it slow, breathe in and out the beauty of the language. OR, I like to devour it in one sitting, holding my breath and wanting more. So, it’s a little surprising that I’ve pulled the last paragraph of a book to use as a craft study.

I am not one of those people who jumps to the last few pages to read how a book ends before I’ve ever started it. I do not understand those people. At all. I like to savor a good book, take it slow, breathe in and out the beauty of the language. OR, I like to devour it in one sitting, holding my breath and wanting more. So, it’s a little surprising that I’ve pulled the last paragraph of a book to use as a craft study.

world. Seriously. You know when you read a book, and then it haunts you — like forever? This is one of those books for me. I am, and will be, a better teacher, friend, wife, mother, daughter, colleague, leader, consultant because I read this book.

world. Seriously. You know when you read a book, and then it haunts you — like forever? This is one of those books for me. I am, and will be, a better teacher, friend, wife, mother, daughter, colleague, leader, consultant because I read this book.

I listened to the audiobook, and liked the novel so much I had to go and buy it in hardback for my classroom library. The story still haunts me. (I read it soon after I read Jellicoe Road, and that story haunts me, too. These two books make an interesting pairing.)

I listened to the audiobook, and liked the novel so much I had to go and buy it in hardback for my classroom library. The story still haunts me. (I read it soon after I read Jellicoe Road, and that story haunts me, too. These two books make an interesting pairing.)