I know the importance of listening, mainly because I know what it feels like to be ignored. To share an idea, only for someone else in a group to quickly move on to something else. What happens next? Silence. This is exactly what I don’t want in my classroom. I want my students to feel comfortable enough to speak up and write about topics that matter to them. I want them to see that I care, and I am listening.

This is where the freedom of the workshop model comes in handy.

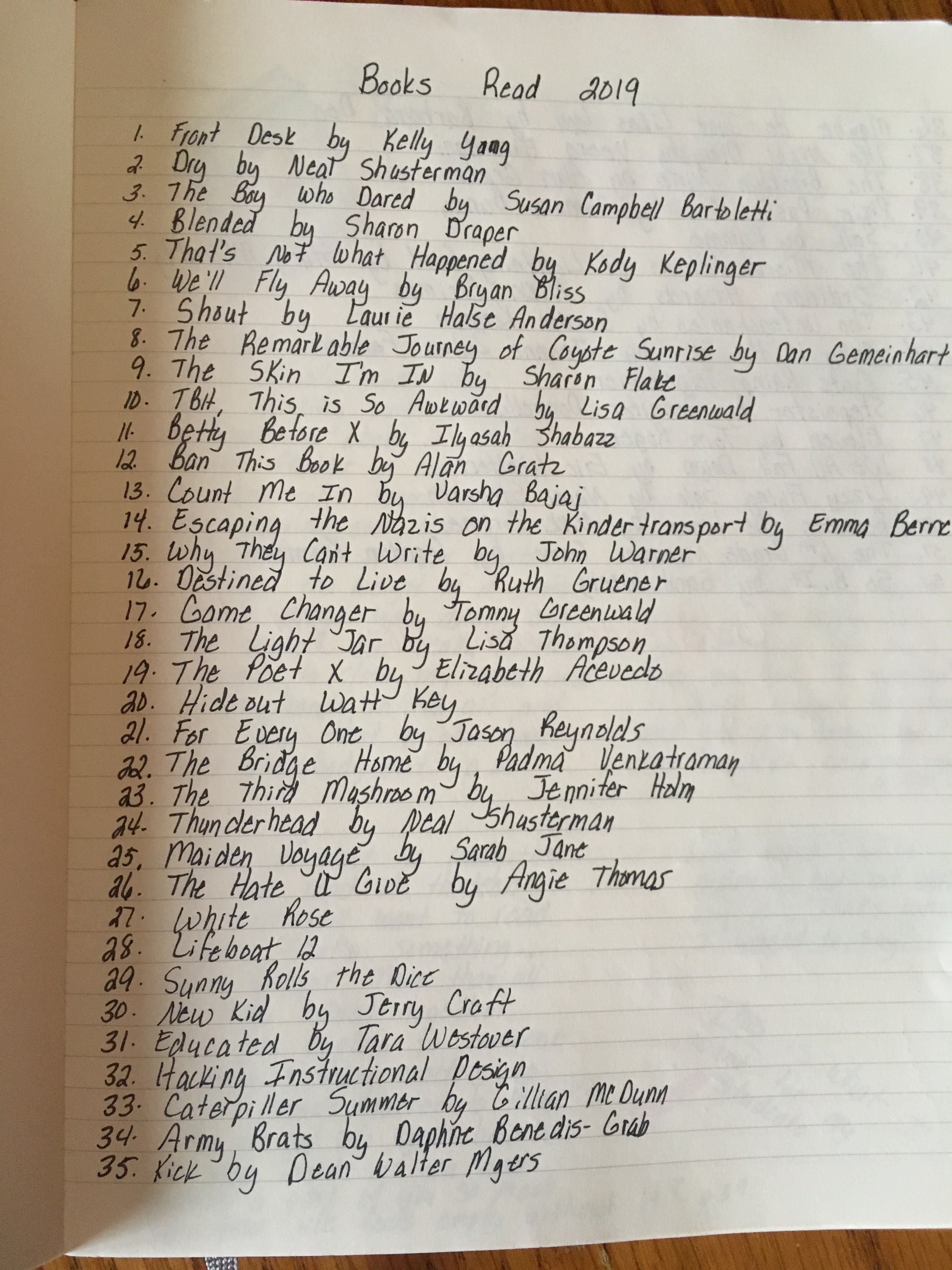

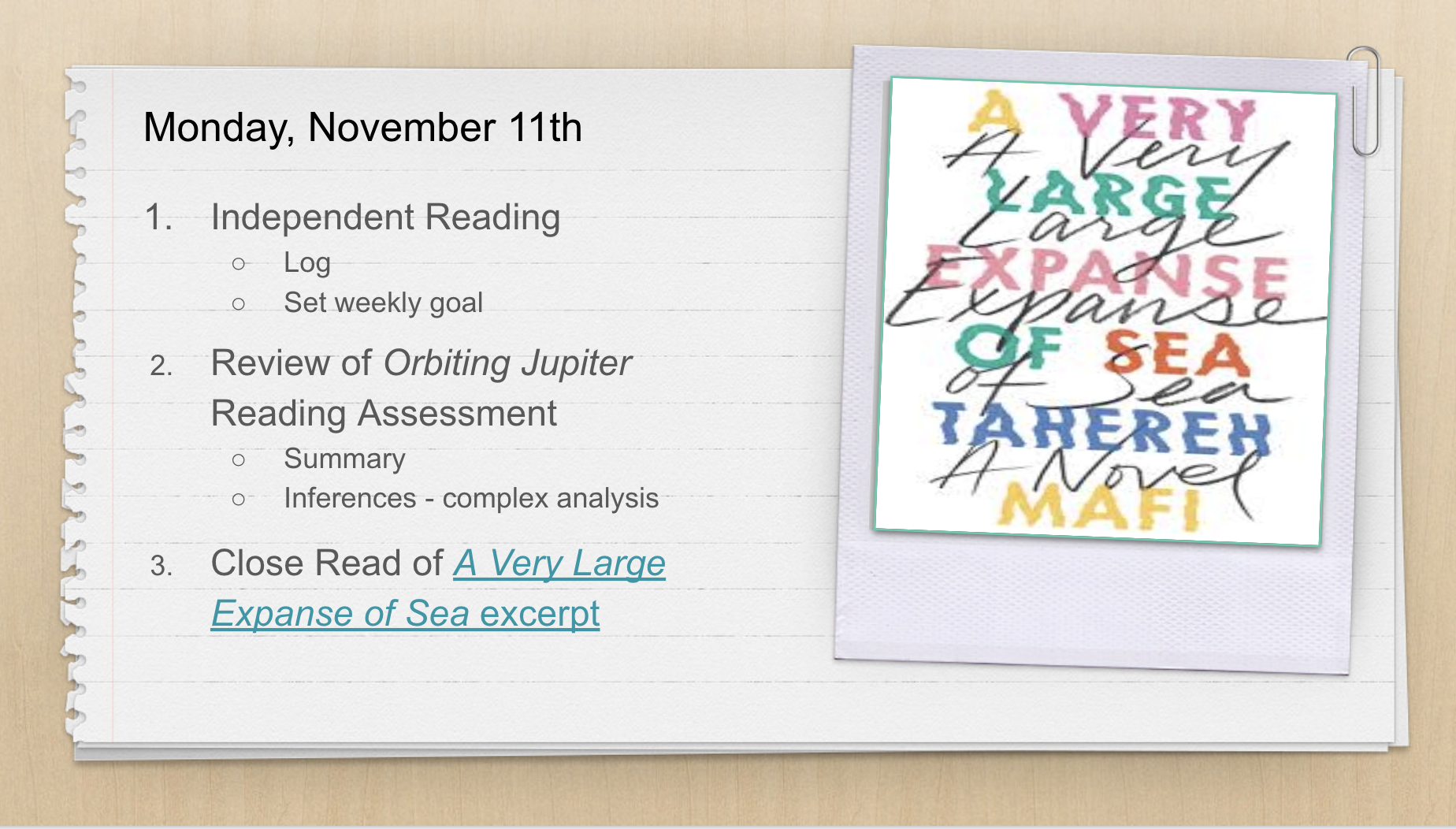

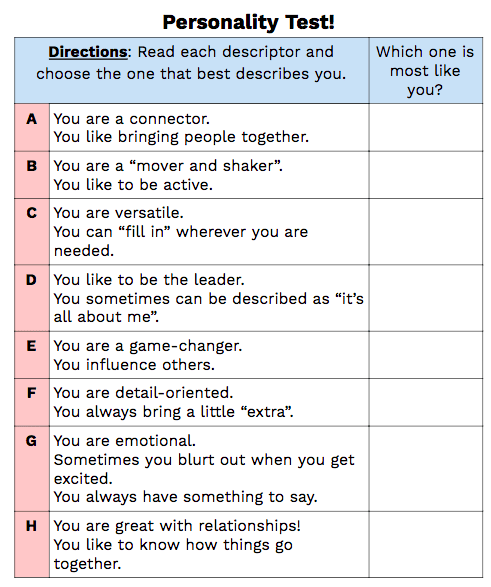

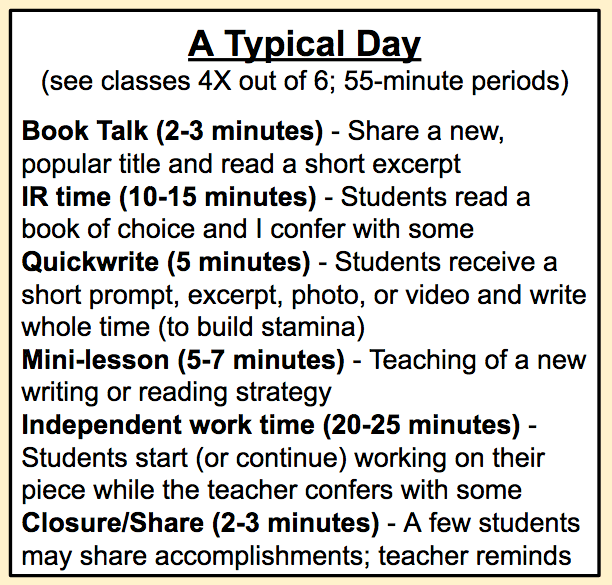

For book talks, I choose titles that are written by authors that students love, or need to be introduced to. (I have students complete a survey at the beginning of the year so I know what they like and dislike right away.) I choose excerpts that they can connect with, and others that will shock them. Their to-read lists grow longer and longer.

During independent reading, I can confer with students. Sure, it’s often about the titles they are reading, but sometimes it’s my way of letting them know that I see something is different, and possibly wrong. I can check in and see what I can do to ease a worried mind. Or, maybe it’s my chance to applaud them on a job well done.

Quickwrites can incorporate poems, video clips, and excerpts that connect to topics students long to discuss. School should be a place where students can speak freely about topics like anxiety, current events, racism, the difficulties of growing up, and so much more. The possibilities are endless.

Mini-lessons may be brief, but I can work in some of my own writing here. This is where I put myself on display, and students can see I am a struggling writer just like them. Comfort and ease are added to our classroom.

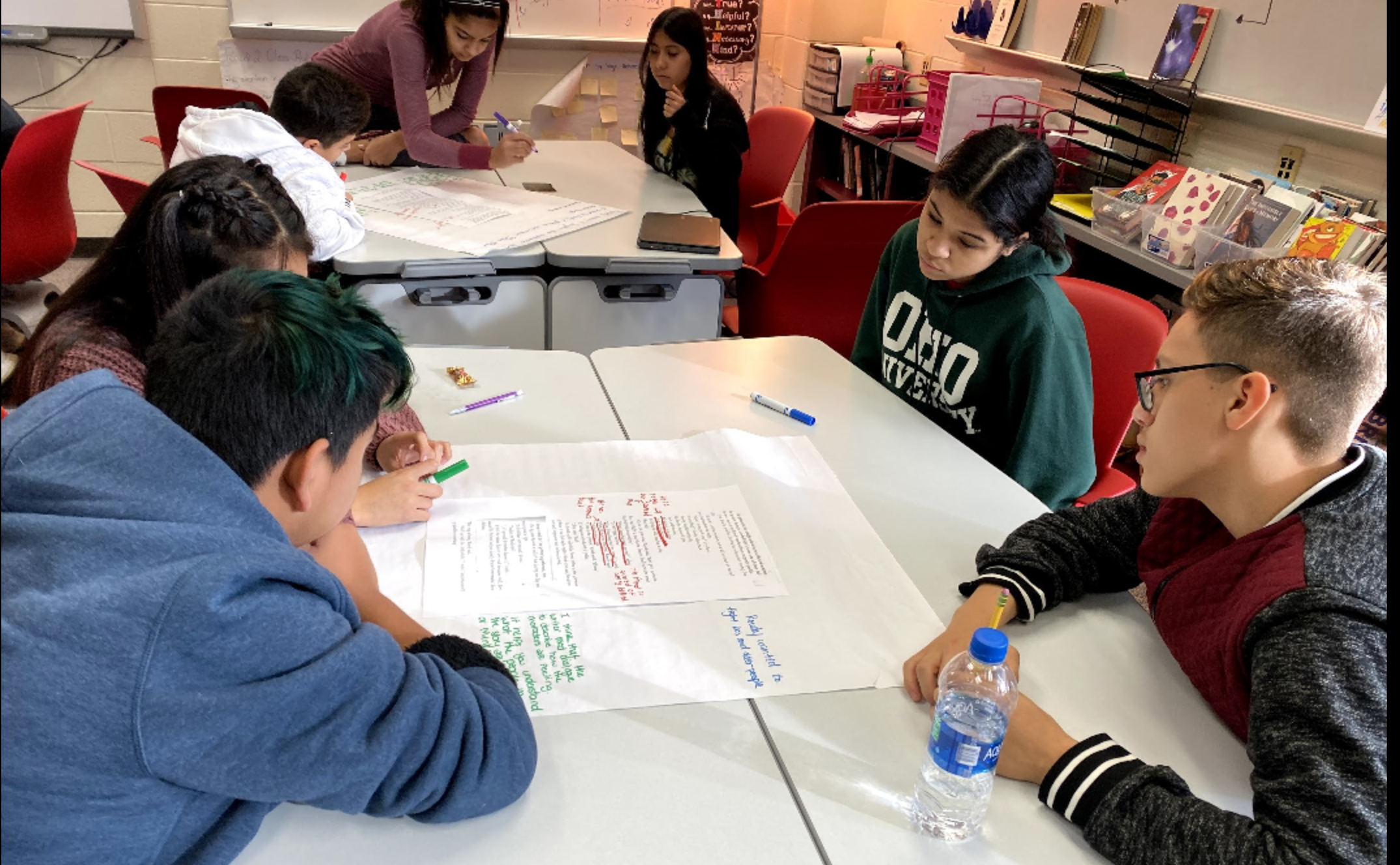

Independent work time provides another opportunity for sharing ideas, whether it be through talk or writing. Students can write a piece with a peer, or one that’s all their own. Students can share their passions and frustrations in small-group or whole-class discussions. I can check in with them. I ask questions, if they need assistance, and what’s something they are proud of.

Finally, we share. Students share a new idea, a line they are proud of, or a word they’ve never used. We applaud one another. We build our community.

In today’s world, I am proud that I can give my students a classroom that is safe and inviting. Workshop makes that possible.

Sarah Krajewski teaches 9th and 12th grade English and Journalism. She is currently in her 18th year of teaching, and is always looking for new, creative ways to help her students enjoy learning, reading, and writing. At school, she is known for dedicating her time to helping students become lifelong readers and writers. At home, she is a proud wife and mother to three readers. You can follow Sarah on Twitter @shkrajewski and her blog can be viewed at http://skrajewski.wordpress.com/.