Testing season is upon us. Heaven help us all.

ACT, SAT, AP – insert your high stakes, hive-inducing, pencil-sharpening acronym here.

As students sit down to demonstrate, in bubble form, their proficiency as scholars (and sometimes in their own estimation, as human beings), we as educational professionals hold our collective breath.

Have we balanced real world application of skills and test prep as we should?

Will students be able to develop their ideas in the limited time provided?

Do they know the specific language necessary to decode the test?

Will they demonstrate growth reflective of the hard work of both teacher and student?

What will these scores mean for my daily practice? My salary? My job security?

It can sometimes feel desperately difficult to maintain the freedom, choice, and empowerment that workshop affords in the face of district expectations for test performance. Afterall, students aren’t given choice when it comes to test prompts or format, or taking the test at all. However, at the end of the day, the skill focus of both readers and writers workshop speaks pointedly to preparing students for whatever they might encounter on such tests, as learner investment in choice materials in often much higher. So if we work to illustrate key skills in mini lessons and have students work with those concepts utilizing texts they are enthusiastic about, research would suggest a solid return on investment, both scholars and the tests used to measure their “proficiency.”

For example, Greene and Melton’s book Test Talk: Integrating Test Preparation into Reading Workshop stresses that successful test takers must be smart readers.

Many test taking strategies are simply good reading strategies, so as we work to build student skills in close reading, we are also building their test-taking skills. In this way, test review isn’t an isolated unit, but rather a daily practice that teachers can refer students back to as test time approaches. And because better reading means better writing, the need to develop students as careful readers is paramount.

So while the beauty of workshop is choice, our world of standardized tests demands the development of specific reading and writing skills; however, those two worlds can have more in common than we might initially think.

To illustrate, I took my AP Language students through a prompt review that challenged them with timed writing, analysis of student samples, self-assessment of their work, peer-assessment of their work, and then collaboration to arrive at a final score.

Obviously, part of the written test is one’s ability to write an argument, but in the case of this synthesis prompt, if students aren’t careful readers of the materials provided, they struggle to effectively incorporate the evidence. This specific test prep went way beyond the test in terms of skill development and it went down like this:

- Students wrote an AP Language Synthesis essay in class. This required 15 minutes to look at sources and 40 minutes to write an argument essay utilizing those sources to support their claims. AP Synthesis essays ask students to write an argument and incorporate at least three of the provided sources. Students must quickly read through the source material to locate information they want to use in support of their claims and then plan, organize, and write their essay.

- The following class period, we looked at student samples and the AP scoring guide from the College Board website. This gave students an idea of what the prompt looked like in action and the actual scores those students received. I divided the class into groups, had each group look at one sample essay and its score. They then had to justify how AP scorers came up with that score. We shared as a class that lower essays lacked organization and analysis, middle scoring essays were adequate in all areas but could be improved with more specifics and developed analysis of included source material, and the top scoring essays blend style and content in a mature fashion.

- Students then pulled out a clean sheet of paper and self-assessed using the provided rubric by giving themselves a score and justifying it.

- Here’s where I tried something new. Students folded over the top of their assessments and handed their synthesis essays and the reflection (without their score visible) to the person next to them. Peers read through the essay, scored it, and wrote several suggestions for improvement. We went around our tables of four until each student had his or her essay back.

- We then unfurled their feedback and engaged in collaborative discussion. I asked students to talk about what they saw in each other’s essays and to arrive at a final score. I recorded this in the gradebook as their formative score for the exercise. Anyone that was dissatisfied with what the table decided, could come and share their concern with me, which I am pleased to report, did not happen.

- Students stapled their feedback form to the essay with a final score on top, along with their thoughts on the exercise.

In the end, students said it was hugely helpful to compare their work to that of others and in doing so, realize what they could do to improve their own responses on the actual test.

Eva said she found the activity, “Really, really helpful. It’s good to get perspective and to be able to reflect from that feedback. 10/10 :)”

Sam suggested that it was helpful because he finds it “hard to critique” his own work. Having published student samples from AP and peer samples from his group, he was able to compare and contrast against concrete scored examples and try his hand at assigning a score on his own, with his tablemates to help justify that score at the end.

And Daaman said she, “enjoyed this activity as we were able to see others’ interpretations of the prompt and also see ways we can improve.”

I’m glad they feel more prepared for the test, but beyond that I am most impressed that in just two class periods they demonstrated skills in both reading and writing, analysis, synthesis, reflection, and collaboration. By analyzing student samples as mentors and applying that knowledge to their own work, students walked away with several examples of what to do, what not to do, and where to take their writing for the next argument we write. No bubbles or number two pencils required.

How do you bring workshop and standardized testing together? Please leave your ideas and comments below!

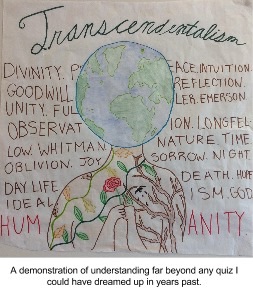

worked in and around the essential question, “What is the relationship of the individual to the community?” Through the study of a variety of essays, including everything from Henry David Thoreau’s

worked in and around the essential question, “What is the relationship of the individual to the community?” Through the study of a variety of essays, including everything from Henry David Thoreau’s  As these kids get ready to head off to a world beyond the insulated suburban existence most of them have known all their lives, they know many of their foundational communities will be changing. For some, this change can’t come soon enough. For others, I think it will be a rude awakening. And still others, a chance to move toward the authentic selves that they so desperately need to discover.

As these kids get ready to head off to a world beyond the insulated suburban existence most of them have known all their lives, they know many of their foundational communities will be changing. For some, this change can’t come soon enough. For others, I think it will be a rude awakening. And still others, a chance to move toward the authentic selves that they so desperately need to discover. short, students captured the movements and we hung up the evidence to remind us of the context of what we were exploring.

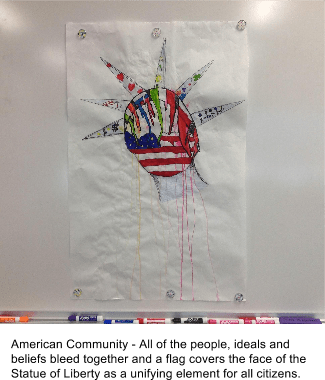

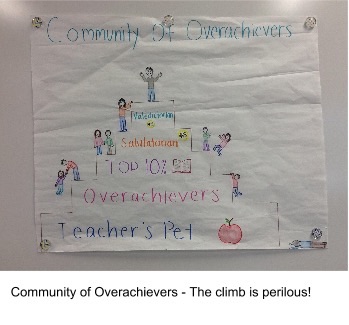

short, students captured the movements and we hung up the evidence to remind us of the context of what we were exploring. Students shared some phenomenal work and I was impressed not only with the depth of their thinking, but the synthesis of texts this activity produced. And, because my own artistic development was apparently arrested in the second grade, it was such fun to see some of my visually gifted kids shine through the use of a new medium.

Students shared some phenomenal work and I was impressed not only with the depth of their thinking, but the synthesis of texts this activity produced. And, because my own artistic development was apparently arrested in the second grade, it was such fun to see some of my visually gifted kids shine through the use of a new medium.