Let me tell you about my fall, y’all. It’s been a doozy.

Depending on which list of the top life stressors you look at, I’ve managed to hit two, maybe three, right on the head. And mine is spinning.

I moved last week. If you’ve ever packed and moved during the school year, you know how stupid I planned the timing. The Rockstars and Tylenol PM have kept me functioning. Some.

Sometimes life gets in the way. Sometimes life gets away from us.

My English department surprised me with this gift of books in honor of my father — one of the sweetest things colleagues have ever done for me. My classroom library is growing!

My father passed away the first part of September. And while he was old, and his health had been fading for a while, his death hit me hard. I used to call him when I drove long distances alone to present workshops. I miss our talks. My dad was a quintessential optimist: wise, encouraging, smart — and he believed in me.

We all need people who believe in us.

Everyday I try to show my students I believe in them. They’ve been so great with all my spinning. Compassionate, kind, studious. Mostly.

I started at a new school this year, and I’ve remembered how much I love working with young people. I also remember how much I detest the distractions: the drills, the mandatory To-Do’s, the paperwork. But that’s a post for another day.

Most days I fake my way — I’ve yet to find a rhythm.

But that’s okay. I believe in the power of authentic literacy instruction. I know those who read and write and communicate well have a better chance at navigating life than those who don’t.

So everyday we read. Everyday we write. Everyday we talk about our reading and writing. Every Friday we discuss important issues. I believe these things trump any other use of instructional time. The routines work. But for many students it is hard.

A few students fake their way — they’ve yet to find their reason.

That’s not okay. I will keep trying. Trying to get books in hands that spark joy in reading, trying to develop writers who believe in the power of words and the beauty of language, trying to get the quiet ones to share their thinking with their peers. They often have the greatest insights.

My evaluator visited my class last week. We were analyzing essays, discussing the writer’s craft –noticing the moves and their effect on meaning– and preparing to write our own Op-Eds. As the administrator left the room he whispered, “It’s hard to get them thinking.”

Yesterday in our writing workshop, right after a little skills-based lesson on making intentional moves as writers, a young man said, “You mean everything I write has to mean something?”

What do you do with that?

I think we have a hard row to hoe, my friends. Gardener, or not, helping our students understand the role of critical thinking in their lives is what may save them. It may save us. It’s saved me for the past few months.

In a Forbes’ article published a year ago, titled “What Great Problem-solvers Do Differently,” we learn five skills that enable people to be great problem solvers: deep technical expertise and experience; the ability to challenge, change, innovate, and push boundaries; a broad strategic focus rather than a narrow focus; drive/push; and excellent interpersonal skills.

I can’t help wondering how I can help students develop more of these skills while in my English class. I know it’s possible. Possibilities mentor hope.

This week a small group of my students — seniors who are eager yet terrified (their words not mine) to face the world after high school — and I chatted a bit about the responsibilities of adulting. I’m afraid I didn’t quell their fears. I might have quickened them.

The stress that comes with independence sometimes sends us spinning.

My students are my witnesses, and while I’d wish it otherwise, perhaps this fall is the most authentic I’ve ever been as a teacher.

Amy Rasmussen teaches senior English in a large suburban high school in North Texas. She tries to write beside her students and wrote this piece as a practice for their Op-Eds. She’s currently trying to unpack and get used to her new commute. Dallas traffic can be a doozy.

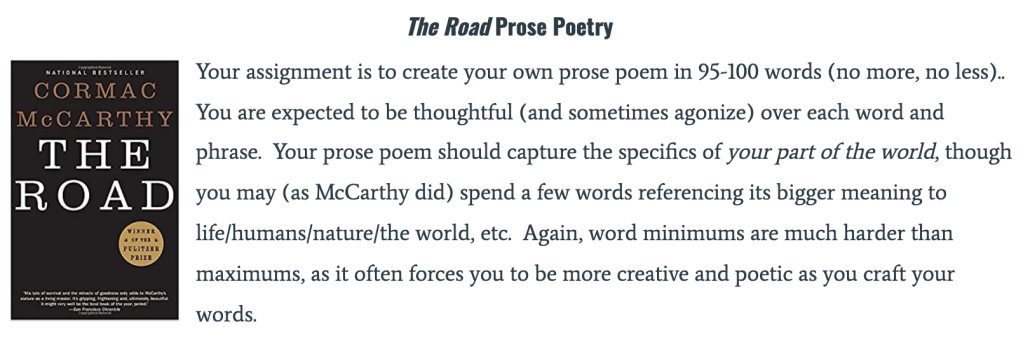

Taking one paragraph each from the sample essays, we read them like writers and explored the decisions and moves made by those writers. Our process of discovery put the cognitive load on the students and allowed me to serve as a “tour guide.” We learned how our argument skills can be applied to this specific writing task, finding new words to add to our personal dictionaries and use in our own writing. We debated the use of claim and evidence and the utility of being intentional with the length of the direct evidence we blend into our argument. We examined the sentence structure decisions made by the writers and noticed how combining sentences can make our writing, and our argument, clearer.

Taking one paragraph each from the sample essays, we read them like writers and explored the decisions and moves made by those writers. Our process of discovery put the cognitive load on the students and allowed me to serve as a “tour guide.” We learned how our argument skills can be applied to this specific writing task, finding new words to add to our personal dictionaries and use in our own writing. We debated the use of claim and evidence and the utility of being intentional with the length of the direct evidence we blend into our argument. We examined the sentence structure decisions made by the writers and noticed how combining sentences can make our writing, and our argument, clearer.