The Beckers are on the move again, which means boxes. Lots of boxes.

I’m no stranger to moving boxes, having packed and unpacked thousands of them over my lifetime. I’ll never forget moving to Seattle, Washington, shortly after my college graduation. Seventeen boxes shipped via Greyhound Bus – yes, leave the driving to us Greyhound Bus – full of blazers with shoulder pads, photo albums, stuffed animals, and books. Lots of books.

It’s hard to believe now that my life fit into 17 boxes then. I’ve added a few more boxes of memories since that first big move to Seattle when boxy blazers were in. Very in.

According to my memory and Mapquest ®, the latter certainly more reliable than the former, I’ve made ten significant relocations, adding up to 20,083 miles moved. With each move comes the sober reminder that while our possessions can be put in boxes to arrive, hopefully unscathed, at our next destination, our memories fade over time, the photograph of what we left behind becoming a little less clear with each passing day, week, and year.

That’s where my writing finds me today – possessions in boxes and memories of the last 20,083 miles of my life still (thankfully) vivid and poignant.

Not calculated in my frequent mover statistics are the eleven miles I moved in Summer 2019 from Clear Creek to Clear Brook High School, and then a few months later, the seven miles I moved from high school teaching to an administrative position in the Learner Support Center of Clear Creek ISD.

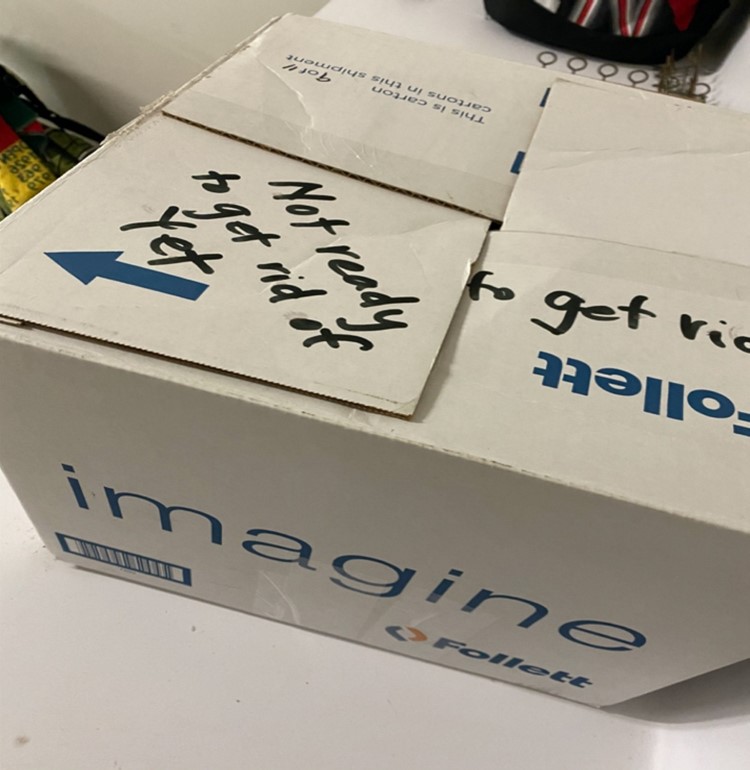

When I left the classroom, I gave away most of my teaching books. But there’s a box labeled “Not ready to get rid of yet” still lurking in my garage, wondering if it will ever go back to a school, wondering why its owner can’t bear to get rid of the contents

Enter the brilliant, sweet, encouraging Amy Rasmussen.

When Amy Rasmussen approached me about writing regularly for Three Teachers Talk, I voiced some concern as to my relevancy, especially since I’m not in the classroom anymore. “Amy,” I emphasized, “I’m in the Assessment Office now.” As if that retort meant I wasn’t qualified to write about writing anymore. But that’s when I zeroed in on the boxes of my teaching life, the years and years of lessons that, even in a new paradigm of pandemic-era teaching, are tried and still true.

So that’s what I’m calling my segment: Tried and (Still) True. The first Monday of each month, I will recap a lesson from my teaching past that still has impact today, a timeless lesson available for teachers to adapt and make their own, much as I did many years ago with my own lessons.

Tried, and (Still) True, Monday, May 3, 2021

“When I Read, I Feel…” List Poem adapted from the brilliant mind of another mentor of mine, the late Shelly Childers.

When I taught Junior English at Deer Park High School – South Campus, many of my students rediscovered their love for reading. Some actually realized for the first time that they liked reading after dreading it throughout previous years of school. And, well, some still hated reading no matter how hard I tried. Regardless, at the end of the school year, instead of having students write a benign reflection paragraph, I had students compose a poem based off a list of adjectives describing their reading lives. Here’s a rough idea of how I paced the lesson:

I began by inviting students to list three (3) adjectives describing how they felt when they read. Of course, I modeled a few words of my own, but since we had previously done some writing with Ruth Gendler’s Book of Qualities, students already had a descriptive vocabulary. After waiting and conferring with students as they thought and wrote, I then invited students to think about the first word they recorded (we called it Word A) and then write three (3) statements that said more (I always referred to that step as say “s’more”) proving the range of their emotions, comparing their feelings to something else, and of course, modeling with my own example. I repeated the instruction for Word B and Word C. I next modeled how to take what we had just written and express it in poetic fashion. When I nudged students to do this next step on their own, the magic happened. Students had words to describe their feelings, and in the end, I got an honest, perhaps too honest, self-assessment of each student’s reading identity.

Teacher note: In most cases, students could generate some surface-level emotions for the first two describing words, Word A and Word B. It was when I asked students to come up with a third word, Word C, to describe their feelings for reading that I hit a core of emotions reflecting a student’s authentic experiences.

Teachers can easily adapt the “When I read, I feel _____” invitation to different tasks: reading, writing, researching,…even moving! Here’s my opening stanza from a work-in-progress:

When I move, I feel free.

I ride the bus in a foreign country,

my new home,

making new friends with my kind eyes and a smile.

No language skills, just an open mind

and open heart.

Open to new adventures.

I bet you’d like to see some student samples, wouldn’t you? I have a few, but guess where I’ve kept them all these years?

You guessed it. They are in the box of things I just can’t bear to get rid of yet. If ever.

Helen Becker currently serves the education community as a Research Data Analyst for Clear Creek ISD in the Houston, Texas area. Prior to being a numbers and stats girl, Dr. Becker taught all levels of high school English for Deer Park and Clear Creek ISDs. Maybe you’ve attended a workshop facilitated by Dr. Becker, or perhaps you’ve been in her Reading/Writing workshop sessions. Or maybe she was your high school English teacher. Regardless of your relationship, you probably know that Dr. Becker wants nothing more than for you to take her ideas, make them your own, and bring powerfully authentic writing experiences to your own classroom. If you want more information on this Tried and (Still) True lesson cycle, feel free to e-mail her at beckerhelenc@gmail.com. She hasn’t packed her computer yet, so it’s all good.

By the way, Dr. Becker really is on the move, this time to a house down the street more fitting for new grandparents!

If you enjoyed this post, read this one from Shana Karnes entitled Mini-Lesson Monday: Imitating Poetry: https://threeteacherstalk.com/2015/10/26/mini-lesson-monday-imitating-poetry/

When students

When students  When I model for my writers what it looks like to read like a writer, we start to notice thing we can do in our own writing, and more importantly, we can start to think about HOW we can do them in our own writing.

When I model for my writers what it looks like to read like a writer, we start to notice thing we can do in our own writing, and more importantly, we can start to think about HOW we can do them in our own writing.

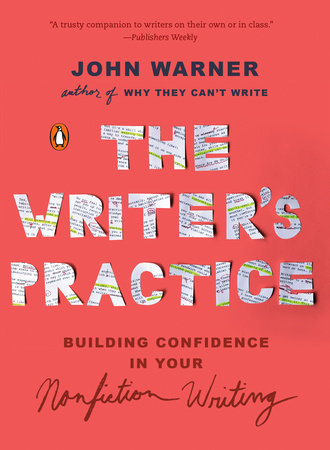

In here, Warner, who’s a college professor, talks about how limiting this kind of writing is, and explores other ways of teaching. For ways of thinking about literary analysis, check out Rebekah O’Dell and Allison Marchetti’s book

In here, Warner, who’s a college professor, talks about how limiting this kind of writing is, and explores other ways of teaching. For ways of thinking about literary analysis, check out Rebekah O’Dell and Allison Marchetti’s book  Like so many teachers blessed with a growth mindset, there are always several ideas bouncing around my head that, if realized, might temporarily satisfy my constant need to innovate my teaching practice. Hopefully, new moves and ideas lead me toward maximizing the delivery of instruction and the transfer of learning. Heading into the TCTELA convention back in January, my head was like a Dumbledore’s pensieve, ideas swirling like memories.

Like so many teachers blessed with a growth mindset, there are always several ideas bouncing around my head that, if realized, might temporarily satisfy my constant need to innovate my teaching practice. Hopefully, new moves and ideas lead me toward maximizing the delivery of instruction and the transfer of learning. Heading into the TCTELA convention back in January, my head was like a Dumbledore’s pensieve, ideas swirling like memories. The first of the year I began participating in the #100DaysofNotebooking. The goal is to write in our notebooks for 100 days. Although I have missed a few days, notebooking has certainly become a habit.

The first of the year I began participating in the #100DaysofNotebooking. The goal is to write in our notebooks for 100 days. Although I have missed a few days, notebooking has certainly become a habit.