Students should write more than teachers can ever grade. I heard this first from Kelly Gallagher, author of the book Readicide, a book, among others, that helped me frame my curriculum around Workshop. If I remember correctly, he said that his students write four times more than he grades. Really?

I pondered this for a long while, and I still struggle, but I think I have some of it figured out. I thought for a long time that my students would not write unless I graded what they wrote. Every assignment: “Is this for a grade?” Every answer: “Yes, everything is for a grade.” The refrain got old.

Then I tried something new: I began writing with my students on the first day of school, and I had some kind of writing activity every single day. I don’t remember where I read it, but when I was researching the work of the reading writing workshop gurus a couple of years ago, I know I read: if you struggle with time and have to choose between reading or writing, choose writing.

It’s the complete opposite of what I thought: My students are struggling readers. How do I give up reading when I know they need it? I thought about it more and realized: If I teach writing well, students will be reading. And they will be reading a lot.

So let me explain how this works for me. Remember, I teach AP English Language and Composition (that’s the top 11th graders) and English I (that’s on-level freshmen)–two extremes.

Writing Every Day

There are many ways to get students to write every day. Of course, some ways will get them to take their writing more seriously than others. I find that when I give them an audience, students will put a lot more effort into what comes out their pens. Audience matters!

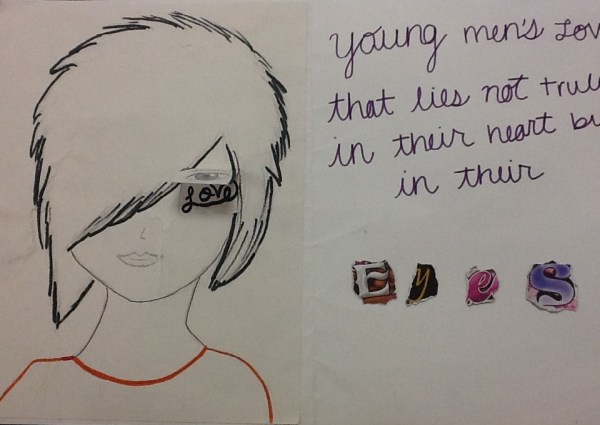

Topic Journals. Following the advice of Penny Kittle, author of Write Beside Them, I created “topic journals” that students write in once a week the first semester. I bought composition notebooks and printed labels, using various fonts, of the topics: love, conflict, man vs. man, man vs. self, man vs. nature, war, death, gender, hope, redemption, family, romance, hate, promise, temptation, evil, compromise, self-reliance, education, friendship, guilt, doubt, expectation, admiration, ambition, courage, power, patience, fate, temperance, desire, etc. I created 36 notebooks; one for each student in my largest class.

I introduced the topic journals to my AP students first. I set up the scenario: “I will be teaching 9th grade. I need your help. Do you remember what it was like to be new to high school? nervous, anxious, a little bit obnoxious? I created these notebooks so you could write and give advice to my younger, less advanced students.”

The first task was to turn to the first page in the journal and define the topic. Many looked up the terms in the dictionary or online. They wrote a quickwrite explaining what the topic meant. Then on the next page they wrote about anything they liked as long as their writing fit the topic. I had them sign their posts with their initials and the class period. I told them that they could choose their form (a letter, a narrative, an advice column) as long as they remembered that their audience was 9th graders, and whatever they wrote had to be school appropriate. “If you write about bombs or offing yourself or anyone else, you’re off to see the counselor or the police.” These are good kids, most of them in National Honor Society. They took my charge to help my younger students seriously. This exercise often worked as a lead into our critical reading or class discussion that day, and sometimes students chose a piece they’d started in a topic journal to continue exploring for a process piece.

You can imagine how I introduced the journals to my freshmen. I began by saying, “You know I teach AP English, right? That’s the college-level English class. Well, those students would like to offer you advice about high school, life, and whatever else you might have to deal with the next few years. They are going to write to you in these topic journals. Your job when you see these notebooks on the tables is to choose the one that “calls” to you. First, you will read the messages the older students wrote for you, and then you will respond. Remember to use your best writing.” I then set the timer and had students read and write for 10-15 minutes, depending on the lesson I planned that day. Sometimes I had students share out what they wrote; most often we tucked the notebooks away for another week.

Students constantly fought over a couple of the topics: love, death, and evil were their favorites. I am certain that is telling (and it did help me when selecting titles for book talks.)

While students wrote in topic journals, I read what students had previously written in the notebooks kids did not select. I’d write a quick line or two in response to something in that notebook. I always used a bright orange or green pen, so students could tell I’d had my eyes in that journal. They knew I was reading them, but they never knew when or what entry. This helped hold them accountable for not only the content of what they were writing but also the mechanics of how they were writing it.

Assessment? Formative. Students have to think quickly and write about a topic on a timed test for the AP exam (11th grade) and STAAR (9th grade).

Blogs

At first I only set up a class blog, and I had students write in response to posts I put on the front page and in response to an article I put on an article of the week page (another Gallagher idea). It didn’t take me long to realize that students would write more and take more ownership of their craft if they created their own blogs. The first year I had students set up blogs I taught gifted and talented sophomores, and I was nervous. Nervous that something would happen: they’d post inappropriate things, they’d do something to get themselves and me in trouble, they’d be accosted by trolls out to hurt children through internet contact. I chose Edublogs.org as the platform because I could be an administrator on the student blogs, and I had my kids use pseudonyms. This was overkill. Yes, I did have to change two things that year: one student called his blog Mrs. Rasmussen. I told him my husband didn’t appreciate that much. Another kid used a picture of a bomb as his avatar. Not funny. All-in-all my students did great, and they wrote a lot more (and better) than they ever did for me on paper. I was a stickler for errors and created this cruel scoring guide that said something like: A=only one minor error, B=two minor error, C=three minor errors, F=four or more errors. Students that had never gotten a C in their lives were freaking out over F’s. “Sorry, kiddo, that’s a comma splice. That’s a run-on.” I had more opportunities to teach grammar mini-lessons than I ever had in my career. But see, these kids cared about their grades.

My 9th graders now–not so much. They care about a lot of things, but if I punish them for comma errors or the like, they shut down and stop writing. I learned to be much more careful. Now, I work on building relationships so they trust me to teach them how to fix the errors themselves. It takes a lot more time, but in the end, student writing improves, and students feel more confident in their abilities. I am still working on getting my 9th graders to be effective writers. So far, I have not accomplished that too well, as is evidence of their EOC scores this year.

This past year my AP English students posted on their blogs once a week. I told them that I would read as many of their posts as I could, but I would only grade about every three. I wouldn’t tell them which ones I’d be grading. I let students choose their topics, but since I had to teach them specific skills to master for the AP exam, I instilled parameters. They had to choose a news article that they found interesting, and then they had to formulate an argument that stemmed from that article. The deadline was 10 pm on Monday–every week. This assignment accomplished two of my objectives: students will become familiar with the world around them, and students will create pieces that incorporate the skills that we learn in class. When I turned to social media to promote student blogs, I got even more ownership from my students.

Assessment? Formative or Summative. Students apply the skills they learned in class regarding grammar, structure, style, devices, etc. Scored using the AP Writing Rubric for the persuasive open-ended question.

Twitter in the Classroom

One of these days I will write a post about the many ways I used Twitter in class this year. For now, let me just tell you: Twitter was the BEST thing I added to my arsenal of student engagement tools. Ever.

When I began asking students to tweet their blog url’s after they wrote on Mondays, I started leaving quick and easy feedback via Twitter. It was so easy! Kids would tweet their posts; I’d read them; re-tweet with a pithy comment. Within minutes of the first couple of tweet exchanges, students were posting and tweeting more. They were getting feedback from me, and they were giving feedback to one another. They began building a readership, and that’s what matters if students blog. Just because they are posting to the world wide web does not mean anyone is reading what they write. But, a readership, especially one that will leave comments, that’s a whole new story.

Assessment? Formative. Students share their writing and make comments about their peers’ writing. Critical thinking is involved because students only have 140 characters to express their views.

Student Choice. Sometimes.

In a perfect writing class, I am sure students get to choose what they write about every time. This does not work in an AP English class where I am trying to prepare students for that difficult exam. Once a week my students complete a timed writing where they respond to an AP prompt. The guidelines for AP clearly state that the essays are scored as drafts; minor errors are expected. My students must practice on-demand writing. There is no time for conferencing or for taking these essays through the writing process. Unless–we revisit. And sometimes we do. Students are allowed to re-assess per our district grading policy if they score below an 85. 85 is difficult for many of my students, so lots of them re-assess. To do so, students must come in and conference with me about their timed writing. I am usually able to pick out the trouble spots quite easily, and it’s through these brief conversations that I get the most improvement from student writing. Often, instead of conferencing with me, students will evaluate their essays with one another.

I show several student models of higher scoring essays and teach students how to read the AP Writing Rubric. Then, in round robin style, students assess their own essays and at least three of their peers. I remind students not to be “nice” to their friends and give a score that’s undeserved. This will not help anyone master the skills necessary for the AP exam. Rarely do students give themselves or their peers scores higher than I would.

My students also write process papers. For AP reading workshop students choose a book from my short list. After reading and discussing the books with their Book Clubs, students have to write an essay that argues some topic from the book. I model how to structure an essay. I model how to write an engaging introduction. I model how to imbed quotes and how to write direct and indirect citations. I model everything I want to see in this type of writing.

I allow several weeks in my agenda to take these papers through the writing process, and students do most of the work outside of class (not so with my 9th graders).

- Day one students generate thesis statements, and we critique, re-write, and re-critique.

- Day two students bring drafts that we read and evaluate in small groups. (I have to teach them that a draft is a finished piece that they are ready to get feedback on–not a quickwrite. So many students type up their rough draft and call in good. This makes me crazy! And I tell them that I will not read their first draft unless they come before or after school or during lunch. They must work on their craft before I will spend my time reading it.)

- Day three students bring another draft that we read and evaluate again. Sometimes, depending on where my kids are in terms of producing a good piece, I will take these up and provide editing on the first page. Never more than the first page!

- Day four students turn in their polished papers. I score them holistically on a rubric that aligns with the AP Writing one, or if it’s my 9th graders, I score them on the appropriate STAAR writing rubric.

My freshmen students need a much more hand holding, and we do a lot of writing on lined yellow paper. Most often, especially at the first of the year, they get to choose their own topics. However, I have to give them a lot more structure because on the new Texas state test. 9th graders have to write two essays (about 300 words each): a literary essay, which is an engaging story, and an expository essay, which explains their thinking about a given prompt. Students use the yellow paper to draft during class. I wander the room, answering questions and keeping kids on task. I also try to write an essay every time I ask students to do so. I use these essays as mentor texts in addition to mentor texts I find by professional authors.

Usually I begin class with some kind of mini-lesson if students are in the middle of drafting. I might show students a paragraph with a description that uses sensory imagery and instruct them to add some description in their own writing. Or, I might teach introductory clauses and have students revise a sentence to include one or two or three. This way I am able to get authentic instruction that my students need right there in the middle of their writing time. When I score these student papers, I specifically look for the skills I’ve explicitly taught. If I do it right, I will have read my students papers one or two times during their writing process, prior to them ever turning in their final draft.

Notice I said “if I do it right.” I rarely do it right. I am still learning to budget my time and get to every kid. I am still learning to get every kid to write. I am writing English I curriculum this summer, which I will use in the fall. I hope to get some of my challenges with my struggling students worked out as I focus more purposefully on the standards. I realized this year that while I am teaching writing as a process all the time, I am not necessarily targeting the standards that fit into the process. I am thinking about this a lot lately.

This is still my burning question: how can I get kids who hate to read and write to participate in writing workshop so their writing improves and their voices are heard?

I am turning to the gurus as I research and think this summer. Jeff Anderson’s book 10 Things Every Writer Should Know has been an excellent start.

For a teacher like me, this moment was a pretty big deal. I attended the University of New Hampshire Literacy Institute and learned from Penny Kittle for two weeks. Her class was called Writing in the World, and I have to tell you, I learned more than I could have hoped for when I set off with my new green notebook for New England, a place I’d never been.

For a teacher like me, this moment was a pretty big deal. I attended the University of New Hampshire Literacy Institute and learned from Penny Kittle for two weeks. Her class was called Writing in the World, and I have to tell you, I learned more than I could have hoped for when I set off with my new green notebook for New England, a place I’d never been.