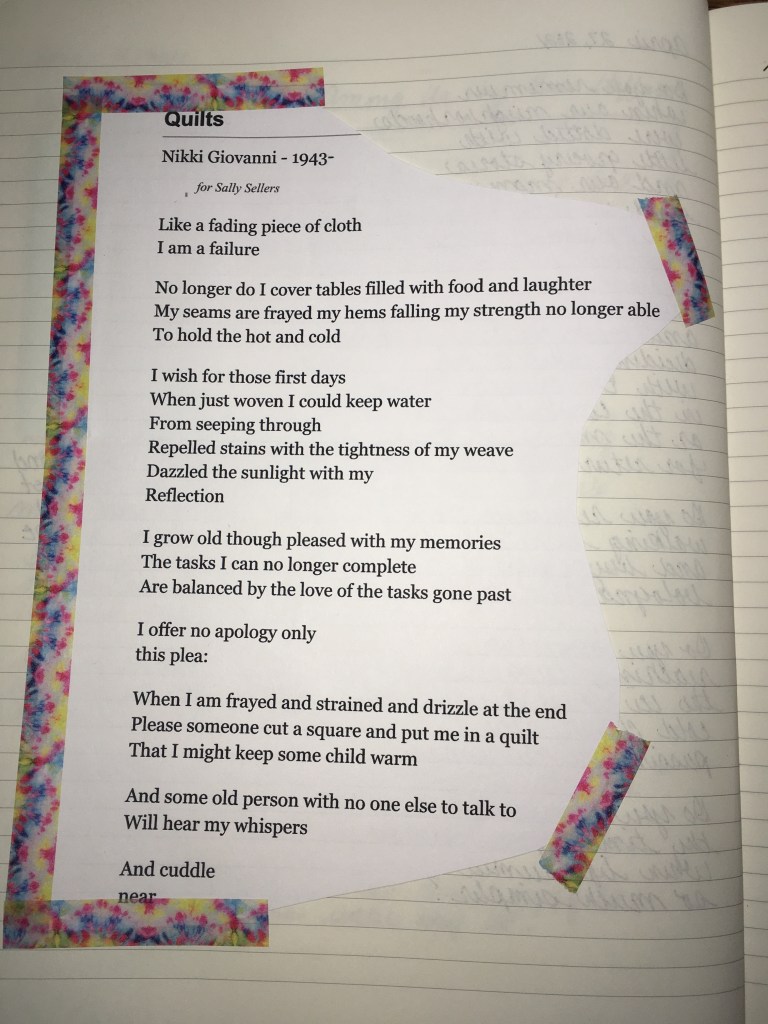

When we were starting our Transcendentalist unit this year, we did a “nature walk” to try to get our students to experience some of the tenets of the concept. We were inspired by this teacher’s blog. My whole team took our students outside (and told online students to set a timer for about 15 minutes and sit outside as well). We left all electronics in the classroom and simply took in the nature outside of our school with all five of our senses. It wasn’t perfect since we were right by a traffic-filled main road and the students really wanted to talk instead of being quiet, but a lot of students got the hang of it by the end. One student reflected that they had not spent any quiet time outside to just take it in in years, if ever. Many were inspired to write like I am at the beach- more on that later.

The 2020-2021 school year has been one of tremendous growth for us all, whether we wanted to grow or not. I spent my year learning how to be even more flexible than ever before, becoming more clear on what is a priority and what can be left for later, and finding myself in a team leadership position when I was the only certified teacher present on my team for over two weeks. However, I do not feel I have grown in my teaching practice as much as I have in my character growth. For that reason, I am seeking situations to put myself in where I am uncomfortable to grow in that area; becoming a contributing writer on this blog is one of them. I am terrified!

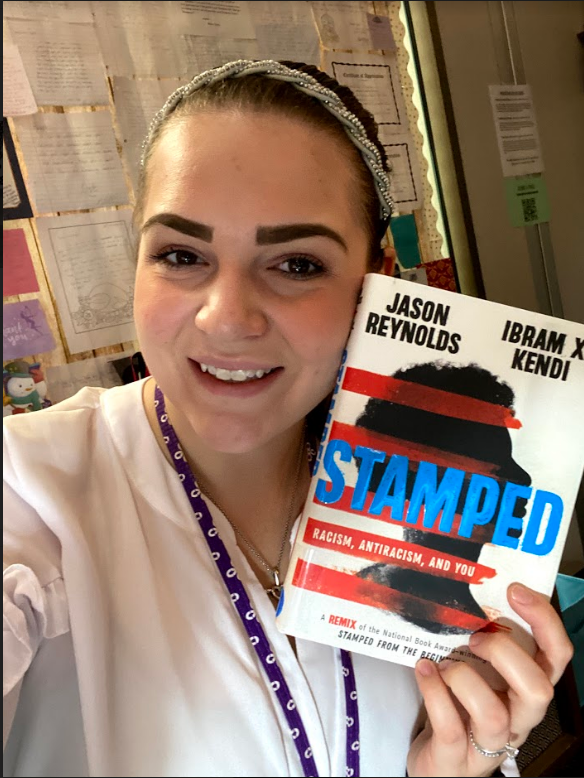

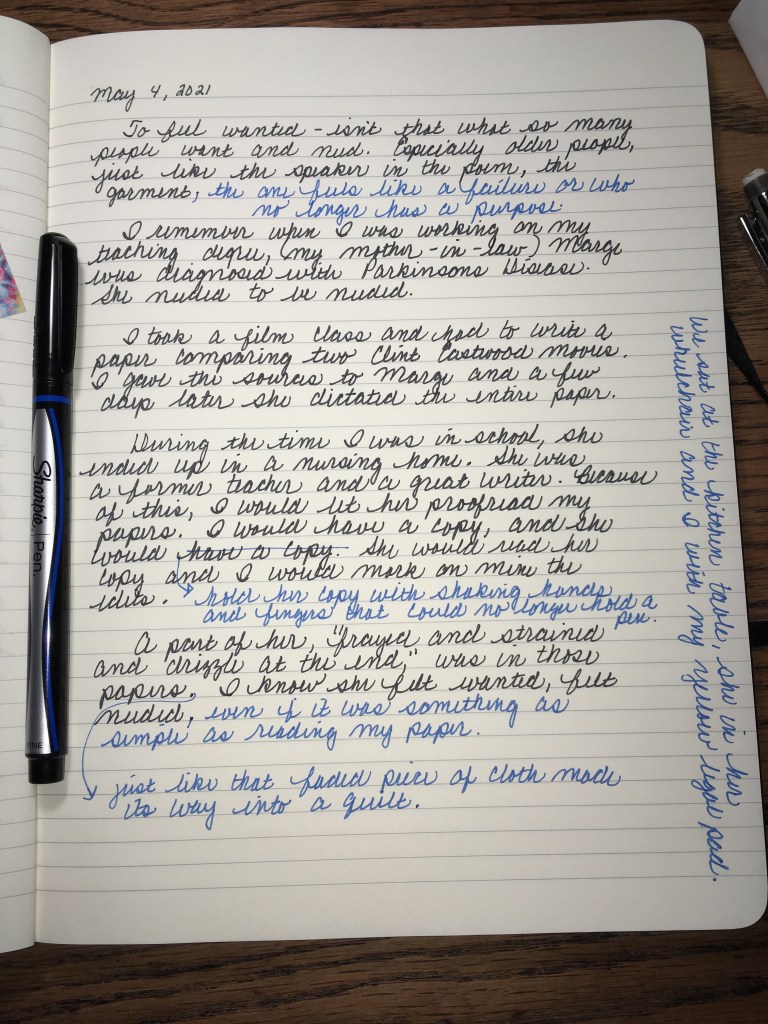

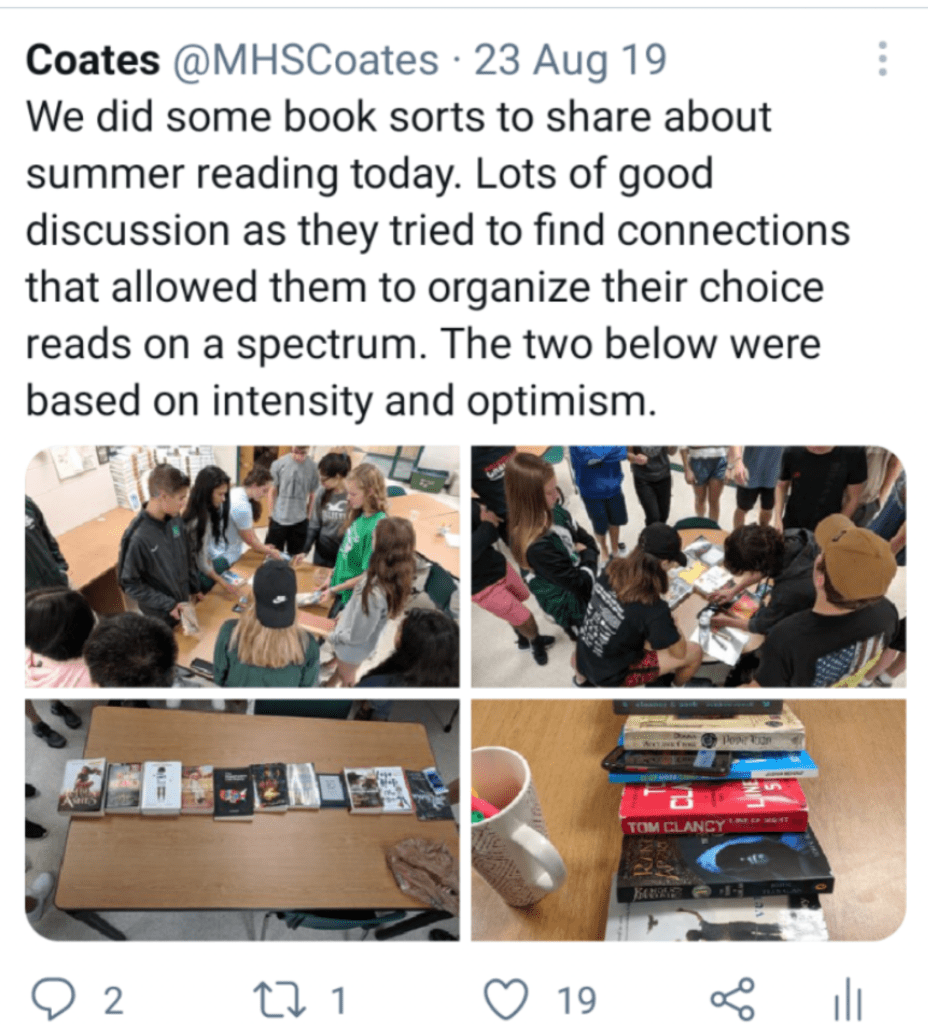

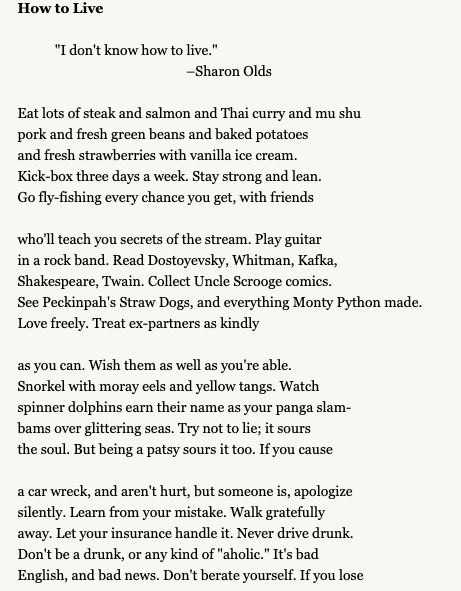

Through my four years of teaching, I have mostly mastered the art of independent reading in class and using that to help students master/demonstrate mastery on most essential standards. I have become a pro at book talks and first chapter Fridays and reading conferences and recommending books. Now that I feel like I have my feet firmly planted underneath me with reading, it is time to become a better writing teacher. Writing is not usually a practice I partake in myself outside of school as I do reading. To be honest, it scares me! Will I have interesting things to say? Am I using a diverse enough vocabulary? Am I creative enough? I prefer my comfortable, familiar cocoon of reading, but I am forcing myself to Write Beside Them like Penny Kittle encourages. I will be re-reading that book over the summer as I make that the focus of my growth for the year.

When thinking about improving the writing part of my teaching practice, I reflected on where I felt most inspired to write. Without a doubt, it is when I am in nature like my students above. My friends will tell you that I wax poetic and create all sorts of metaphors when we are at the beach. For example, there is nothing like staring up at a starry sky while laying in the cooling sand of the beach and hearing the salty water lapping up. The more you look up at the sky, the longer you take it all in, the more stars appear. It gets more beautiful, more bright the longer you take the time to look at it. That always stands as a metaphor for many things in life for me. When we slow down and just stay present, the more beauty we see.

Taking both my experiences in nature and my students’ experiences, I have made a commitment to spend my summer outdoors with my notebook and pen in hand as much as possible to just be present and write as I feel led. How will you get uncomfortable this summer/next school year to grow?