For over a year now I’ve written and published book reviews.

More specifically, I force myself to write book reviews.

Sometimes I have to set an appointment on my calendar. Sometimes I have to shove off other things I want to get done. Sometimes I find ways to creatively prolong my book review journey with the beauties of the internet. Truth be told, there are some kinds of writing that I prefer to do over others, and book reviews are not one of my favorite genres.

With experience and practice, though, I’ve found a book review method that works for me:

Step 1: Read a book carefully (in this case, March Book 3) and annotate with small post-it notes. Annotate for ideas and for details: character names, locations, major events. In other words, scribble down words.

Implications for teaching: My “jots” during the my heat of the moment reading on my mini-post its are a few words at most and are my internal language for ideas that aren’t full-fledged yet. Like many students, I just want to get back to the story and I don’t want to be bothered writing the whole idea out right now. I want to rethink whether I ask students to share their initial jots and annotations with me, and I might instead ask students to revisit and polish up an initial jot into a 2-3 sentence complete idea jot.

Given a chance to stretch out my initial “law and enforcement of the law” jot, I might write:

Civil rights demonstrators were actively testing the practice of federal laws, such as the right to vote, while local law enforcement were breaking the law by preventing the law from being practiced. It’s ironic that the demonstrators are the lawful ones and the police are the criminals, and yet the demonstrators are the ones who end up in jail.

Step 2: Take a break.

Step 3: Engage in some form of “writing off the page” as Nancie Atwell called it in which you engage in low-stakes discovery writing. If I’m in a super-hurry, I skip this step, but I think my reviews suffer for it.

Implications for teaching: I noticed that I needed a sentence started to shape my thinking (this book made me think more about….) I’ve transitioned from calling this process “brainstorming” to “discovery writing” in order to emphasize its true purpose – discovery. I find some students have significant difficulty with true “brainstorming,” only writing down an idea once they’ve thoroughly chewed it over and deemed it good enough. Discovery writing is “good enough” when you discover an idea you didn’t know you had before you sat down to write.

Step 4: Given my knowledge of how book reviews go, I plan for each section. When I was a kid, I used to be disappointed that the New York Times book review didn’t come with “thumbs up” or star ratings like the movies did. After some frustrating trials, I figured out a book review’s secret: the last paragraph is the most important paragraph, and the rest of the review serves as a windup to that last paragraph’s pitch, describing the book’s strengths and then its weaknesses.

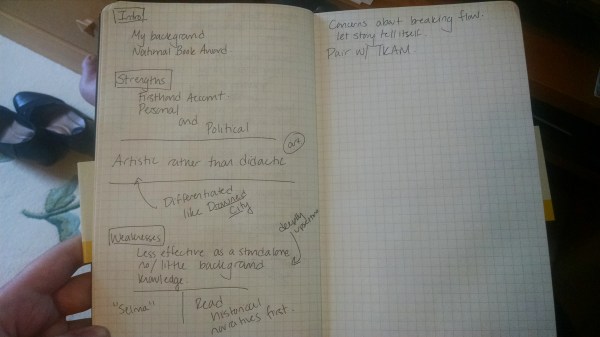

I labeled my notebook with the most important components of the book review: Introduction, Strengths, Weaknesses and Conclusion. (Note too that I added a component for “art” — I find it hard to write about a comic book’s art!)

Implications for teaching: We need to teach readers and writers the essential components to the genres they are writing and reading in and the shortcuts. Just the way we might model a character arc with a novel, we should model the expectations of what to read for within a genre and help students notice when a piece conforms to those general expectations. We can also teach students how to skim nonfiction and how to go back in to understand details after an initial reading.

Step 5: Write the review. My final review almost never looks exactly like my plan, as I do some discovery along the way. However, the outline allows me to “see” my work from beginning to end before I write it, so I write with confidence.

Implications for teaching: We should encourage students to outline, but we should also encourage students to improvise as well. The inexperienced cook refers back to her recipe constantly, always wondering if she got the measurements right, while the more experienced chef can add, improvise, and change along the way if he wants to try out an idea. I’ll be honest – I keep my outline in front of me as an artifact more than anything else to remind myself that I have something to say.

Amy Estersohn is a middle school English teacher in New York. She has purchased an additional copy of March: Book 3 because she wanted a copy that had the award stickers on it. It’s not the silliest reason she’s ever purchased a book.

I love hearing how your work outside of the classroom filters into it!!! Voices from the Middle has a call for proposals about this exact topic right now: http://www.ncte.org/journals/vm/call

I’d love to hear more about how your students worked on their own book reviews and how this impacted their learning!! 🙂

LikeLike