This summer, we’d like to return and talk about some of our most useful, engaging, or popular posts. Today’s post, written by Amy in 2015, makes the case for choice reading in AP English.

This summer, we’d like to return and talk about some of our most useful, engaging, or popular posts. Today’s post, written by Amy in 2015, makes the case for choice reading in AP English.

Please return to this topic and talk with us in the comments–does choice reading belong in AP? How do you put student autonomy at the center of your AP classes?

I’m going to just say this right up front: I hope to challenge some thinking.

I asked some friends for feedback on this post and got opposing advice. I let it rest for half a week. I prayed about it. And then today I read this post by Donalyn Miller, author of The Book Whisperer and Reading in the Wild. I’m not positive, but I’m pretty sure she wrote it in a response to a comment on this post by Amanda Palmer, Secondary Language Arts Coordinator in Katy, TX. I’ve written about my own students and their experiences as they’ve grown as readers before at Nerdy Book Club and on this blog; and I’ve presented on how I advocate for choice in AP English at conferences.

I hope I can be a voice of reason and an inspiration for the good of all students. So, if you’ll hang with me here, I’ve got a case for choice reading in AP English.

“I wish my daughter was in your AP English class,” my friend told me. “She has to decorate Kleenex boxes in hers.”

We’d had this conversation before: I am an advocate of self-selected reading, and I fully embrace readers and writers workshop in my AP English Language and Composition classroom; Sarah is an advanced reader in an AP English course where the teacher chooses all the texts and assigns “clever” ways for the students to show that they are reading. Anyone who knows Penny Kittle’s work, and Donalyn Miller’s work, and my work, which is so much about helping students develop as life-long readers, understands that Sarah is not having the kind of experience in her English class that we advocate and hope for all children.

Making the Move to Move Readers

Many teachers and administrators across the country have recognized that students in secondary classrooms are not reading. If students are not readers, they tend to struggle in all academic subjects — not just English. Schools adopt interdisciplinary practices, whole school vocabulary instruction and stop-everything-and-read programs in an attempt to improve reading scores on standardized tests. Many have moved to readers and writers workshop, where choice-independent reading is key, instead of the traditional secondary-English pedagogy where the teacher selects all the texts, usually classics, and all the writing topics a student is expected to write about for class. Those who have made the move will tell you that choice matters, along with time to read and write, when it comes to student engagement and real movement in our teenage readers and writers.

However, from what I’ve seen and heard, most of this choice is happening in general education classes — not honors and AP English. The teachers in most advanced classes I know of are still making all the choices. It’s like we do not trust our high-achieving students to move themselves into complex texts. We focus on the literature instead of the literacy. And we rob children who already have a grasp of language, who already have many of the study skills they need to pass English classes, with the opportunities to grow as much as they are able.

We make changes in our pedagogy that allow our reluctant and struggling learners to grow but not our proficient kids? Where is the sense it that?

Evidence that Readers and Writers Workshop Works

One day last week, I sat and listened to my district’s ELA director share our state re-tester data. I usually hate this kind of meeting, but our gains are huge — due in large part because of the redesign of tutorial lessons, many of which teachers have adopted into their mainstream instruction. The ELA director changed the model and worked closely with North Star of TX Writing Project to produce writing workshop lessons (most of which came out of my classroom and pedagogy) that broke the mold of Response to Intervention. The dramatic increase in re-tester scores (an average of 200+ point increase per student) proves the lessons are working to move student readers and writers. Workshop-style writing lessons and a campus-wide, district-wide commitment to independent reading is working.

Making the Move in Advanced English Classes — or Not

The next day I sat in a meeting with the AP English team on my home campus. (Important note: The same day that in second period a young woman asked me to recommend her a book of classic literature because she wanted to read something more complex. She and I stood in front of my “Challenge Yourself” shelf, and in about six minutes while the rest of the class read silently, I taught a mini-lesson on Gothic literature and the Regency Era and book talked the Bronte sisters’ books and Jane Austen. Rebecca left class with Pride and Prejudice, a book she chose to read because she wanted a romance that sounded interesting.) In that vertical alignment meeting, the conversation bounced around to what students must know and returned a few times to the books “all students must read.” After a while, someone asked me what I thought.

“Is it really about the book, or is it about the reader?” I asked.

“Well, it’s both,” two teachers answered.

“Then why does the book matter as much as the students’ abilities to read the books?”

“Because they will never read these books on their own, and they have to read a storehouse of canonical texts in order to write on the AP Lit exam,” they said.

“So you’re basing the reading lives of all pre-AP students in 9th and 10th grade on one open-ended question on the AP exam their senior year?”

“Well, they also have to analyze a passage,” one teacher added.

“Yes, and that’s like studying lists of SAT words hoping students learn the few out of 5,000 that might be on the SAT exam. It’s a total crapshoot.

“Shouldn’t we be more concerned about students being able to read at complex levels than deciding which books they must read?”

Another teacher joined in “I want my students to be prepared for the kinds of reading they will be expected to know when they go into college classrooms. That is providing equity. If they know The Iliad, Beowulf, Dante, they will be on equal footing as those classmates who read those things at the affluent schools across town.”

“Shouldn’t the equity be in the skills our students possess? Can they read and understand complex texts like the students across town?”

How Do We Know If Students Are Reading

I know that many, if not most, of those students at other schools are not reading those books. Few high school students read the assigned texts in English classes. Ask them. I have student writing from the past five years that tells me in their own words about their reading habits in high school. And there are plenty of well-researched articles like this one from the English Journal that concur. It is true: few high school students read the assigned texts in English classes. Why doesn’t this matter to their teachers?

“How do you know they are reading the independent reading books you let them choose?” a teacher asked me.

“Because I talk to them about what they are reading,” I answered.

“I do that, too, about the books I assign,” she said, but I am pretty sure that her idea of talking about books with students and mine are very different. I call it conferences. She calls it lectures.

I felt disheartened and sad for the honor student at the outcome of that vertical alignment meeting: AP teachers deciding what four books teachers in preAP 9th and 10th grade must teach in order to prepare students for Advanced Placement in 11th and 12th grade.*

I fear that students will be just as prepared as they have been, which in my one-semester at this campus is not much. At the most, they will read four books a year, and the only students who will read the assigned texts are the ones who are readers anyway, who are studious enough, or care about their grades enough, to do what the teacher says. Everyone else will read a little and Sparknotes a lot, listening in to class discussions, and learning enough to pass exams that cover the conflict, plot, symbolism, and theme of the assigned text. Few, if any, will grow as readers who fall in love with words and characters and the beauty and the texture of carefully crafted stories. It happens over and over and over again.

We deprive the students who take advantage of the College Board’s open enrollment policy, the students who voluntarily agree to more rigor, and we allow them to make it through high school English without growing as readers. I would argue that in many cases, there is high probability that they regress as readers.

How does that make any sense?

Looks Like the College Board Advocates for Readers Writers Workshop

The College Board provides course descriptions for each of the 34 AP courses and exams it offers. The descriptions reflect the course material that might be taught in a comparable college course. This makes designing a curriculum relatively easy for many of the courses taught. Biology and World History, for example, have definite knowledge-based skills that must be covered throughout the course. AP English courses are another story. Since first-year college composition courses are so diverse and vary from college to college, the structure of these classes on high school campuses can be diverse as well. AP programs, and even individual teachers, may design their courses based on their own interests and desires. Of course, the AP classes must reflect and assess college-level expectations, but that’s pretty much the only requirement. There are no prescribed essays that students must write, although there are suggestions of form. There are no required novels to read, although there is a suggested list of authors. Suggested being a key word. Teachers have a great deal of freedom in how they design their courses and what they put on their syllabi. See

AP English Language and Composition Course Overview

AP English Literature and Composition Course Overview

We can still read texts spanning from the 1600’s to the 21 century. We can still read literature that we deem important to our literary canon. But do we have to make all the choices in our Advanced Classes?

We can foster literate lives if we will take the same approach to literacy that is working in thousands of classrooms across the country: Readers and Writers Workshop where choice matters and time to read and write mean deep and lasting learning.

So What’s the Real Deal

After talking this over with several of my peers, I’ve decided on a few reasons why honors and AP English teachers refuse to “drink the Kool Aid” (Isn’t that a nice derogatory way of describing readers/writers workshop? I hear it often):

- Some teachers loved the experience they had with literature in their high school English classes. This is the reason they chose to be English teachers. (I am one of these teachers.) They want to duplicate those positive experiences for their students. A worthy ambition. However, I wonder if they have considered how many of their classmates experienced the same excitement at reading (or not) the literature that the teacher mandated.

- Some teachers are not readers themselves. They love the books they’ve chosen to use in their classes, but rarely do they read anything from a best-seller list, or an awards list. They want to stay with what is known and comfortable. Many times these teachers mistake their duty: to teach the child and not the book.

- Some teachers believe that certain pieces of literature must be read by every student on the planet. “If I don’t teach this book, then these students will never read it” is a statement I’ve heard many times. My answer is always “Yes, but many are still not reading it when you teach it.” We ruin the the taste of great literature for many students when we force books on them that they are not ready for. I’ve asked all of my students this year about their reading in 10th grade. Not one of them has said they love To Kill a Mockingbird, one of two books they had to read last year. Why would we want to turn students off of a much beloved book like TKMB?

- Some teachers believe that 10 to 15 minutes of sustained silent reading at the beginning of class is the same as instruction with choice reading. Sure, this reading time, especially if students are reading books that they choose, is important. It is a step. But it is not the same as structuring instruction around readers workshop where students not only read books that they choose, they think about them, talk about them, learn within them. They confer with a teacher intent on moving the reader in the best differentiated instruction possible.

- Some teachers are afraid of giving up control. They fear that if students are all reading different texts they won’t know how to manage the class or guide the learning. This is a valid concern, but it is also something they can learn how to do. Many of us are doing it. We are happy to share how.

I am sure there are other reasons, and really, I mean no disrespect. I know my colleagues are hardworking and loving educators. I like them a lot. I respect them for the work they do, and I am sure that their students are learning in their classes. I know this is true for many other teachers and classrooms across America, too. I just really want to challenge some thinking.

What if we can do more?

Let’s Allow all Students the Advantages of Choice

More than anything, I want all students to have opportunities to rise above the norm, and maybe, just

~Joseph, AP English Language and Composition Student

maybe, we will see many more students, not just our struggling ones, immersed in books they love, and thinking about their reading in ways we’ve never imagined. Their engagement will improve. Their growth will astound us. They will develop as critical thinkers, accomplished writers, and as empathetic individuals ready to take on the challenges of college and their world.

I mentioned at the beginning of this post that I shared a draft of it with my writing partners. This response from Shana is important:

“I was an AP Lit kid, and an Honors English kid. I SparkNoted The Scarlet Letter, Beowulf, Iliad, Catcher in the Rye, and the rest. I never read a bit of it. In fact, I didn’t read ANYTHING that was assigned to me simply because of the fact that it had been ASSIGNED. I was stubborn like that. And I got A’s all the way through. And a 5 on the AP test. All the while tearing through John Grisham, Elizabeth Peters, and the entire Bestsellers section of my public library outside of class.

“Then, my freshman year of college, when I took a workshop class in which I was allowed to self-select what I read, I chose the Scarlet Letter and thought it was the most beautiful love story I’d ever read. I finished it and read it again. Since that day, when I realized that because I was one of those AP kids and I COULD read those works, I’ve discovered that I LOVE them. But I never read a single one of them until after high school. My well-known love for Jane Austen didn’t emerge until I wrote a paper on Pride and Prejudice and A Midsummer Night’s Dream for my Shakespeare capstone. I just read Mockingbird last summer for the first time ever. [Note: I read it when I was 40.]

“I was never allowed to choose for myself in AP or Honors English, but had I been allowed to…I would have read all of those books, and arrived at a deeper level of love and reverence for literature, much earlier in my reading life.

“One thing I might add — I totally disagree with that AP Lit teacher saying that students needed to draw from classic lit for the test. Many of my AP kids who got 5s wrote about modern classics…Oscar Wao, Life of Pi, whatever. You don’t have to know CLASSICS to ace the Lit exam…you just have to know how to write authentically about complex texts, and that’s what we do in workshop, and what kids should be doing in AP classes.”

I know there are others who have made the shift. I got this in an email message just today from Jeannine in CA. We had a nice chat at NCTE: “Thank you for our November communication. I have altered much of my instruction to incorporate choice reading. The students are soaring!!!”

Another AP English teacher trusting herself and her students enough to make a change and see where it takes them.

Why, Yes, There’s Research to Support This Pedagogy

I mentioned Donalyn’s post at the beginning of this long one. It is all about the research, the theory that outlines and supports what it takes to grow readers. Allington, Atwell, Krashen, Moss, Fisher, Ivey, and Kittle, and Gallagher and more.

I add another: Last summer at the University of New Hampshire Literacy Institute Penny Kittle had us read Making Meaning with Texts, Selected Essays by Louise Rosenblatt. Rosenblatt’s research spans decades and is just as applicable today as when she wrote it years ago. I challenge every English educator to read the whole of Rosenblatt’s essay “The Acid Test for Literature Teaching, published in 1956. Or, at least to respond honestly to Rosenblatt’s conclusion. Odds are you will make the shift to choice, if you haven’t already:

“As we review our current high school programs in literature, we need to hold on to the essentials, or take the opportunity as re-adjustments come about, to create the practice that will meet the acid test:

Does this practice or approach hinder or foster a sense that literature exists as a form of personally meaningful experiences?

Is the pupil’s interaction with the literary work itself the center from which all else radiates?

Is the student being helped to grow into a relationship of integrity to language and literature?

Is he building a lifetime habit of significant reading?”

*In an email after I’d written this post, I received the notes from that meeting, and I am happy to say that there were no specific book titles listed, just the admonition that students in 9 and 10 grade preAP classes read 3-5 whole class texts of a complex nature. And students need to read 15-20 books a year to grow as readers. (Yes, I did throw in that bit of research while in that meeting.)

©Amy Rasmussen, 2011 – 2015

This summer, we’d like to return and talk about some of our most useful, engaging, or popular posts. Today’s post, written by Erika in 2014, reminds us of her process for finding mentor texts–they’re everywhere!

This summer, we’d like to return and talk about some of our most useful, engaging, or popular posts. Today’s post, written by Erika in 2014, reminds us of her process for finding mentor texts–they’re everywhere! I know this may be a risky move in my classroom. Yet, I’m going to take a chance. I anticipate shared laughter as we navigate this piece together. I also plan to explore the bunny’s intentions and make it relevant for our work as writers: Why did he feel the need to rewrite the story? Do the illustrations add to the message he is portraying? Do any of his original thoughts (verse his revisions) feel more powerful to you? What intentional moves did he make in re-creating this story? And on and on.

I know this may be a risky move in my classroom. Yet, I’m going to take a chance. I anticipate shared laughter as we navigate this piece together. I also plan to explore the bunny’s intentions and make it relevant for our work as writers: Why did he feel the need to rewrite the story? Do the illustrations add to the message he is portraying? Do any of his original thoughts (verse his revisions) feel more powerful to you? What intentional moves did he make in re-creating this story? And on and on. and talk strategy. I want to use some of these words within my own vernacular and challenge students to do the same. Most importantly, I want to show them that reading is a process; not one to shy away from. And yes, sometimes it takes work, but overtime it becomes natural…and wildly fulfilling.

and talk strategy. I want to use some of these words within my own vernacular and challenge students to do the same. Most importantly, I want to show them that reading is a process; not one to shy away from. And yes, sometimes it takes work, but overtime it becomes natural…and wildly fulfilling. You are a Baddass: How to Stop Doubting Your Greatness and Start Living an Awesome Life by Jen Sincero has found its way into my Survival Book Kit and I love it! I’m just past the first thirty pages, yet I have not stopped laughing. Yes, out loud.

You are a Baddass: How to Stop Doubting Your Greatness and Start Living an Awesome Life by Jen Sincero has found its way into my Survival Book Kit and I love it! I’m just past the first thirty pages, yet I have not stopped laughing. Yes, out loud.

This summer, we’d like to

This summer, we’d like to ![FullSizeRender[1]](https://threeteacherstalk.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/fullsizerender11.jpg?w=181&h=240)

![FullSizeRender[4]](https://threeteacherstalk.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/fullsizerender4.jpg?w=278&h=160)

![FullSizeRender[3]](https://threeteacherstalk.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/fullsizerender3.jpg?w=151&h=198)

![FullSizeRender[2]](https://threeteacherstalk.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/fullsizerender2.jpg?w=167&h=221)

This summer, we’d like to

This summer, we’d like to

This summer, we’d like to

This summer, we’d like to

This summer, we’d like to

This summer, we’d like to

This summer, we’d like to

This summer, we’d like to

This summer, we’d like to

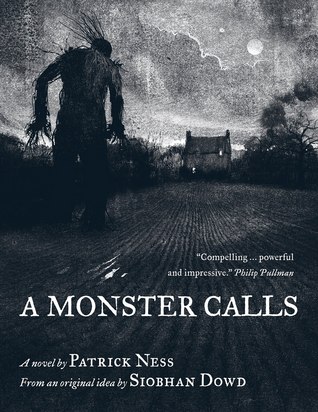

This summer, we’d like to  book talk this story tomorrow, and how transformative I think this text could be for some of my kids, it’s what led me to this text that I find really important right now. As a result, approximately eight minutes after finishing that book, seven minutes after shoving a copy of it into my husband’s hands and insisting he “Read this. Read this immediately” (thankfully we’ve been married long enough that he can recognize a literary induced meltdown and not fear for his own safety), five minutes after texting half my department to tell them of my ugly-cry recommendation, and three minutes after blowing my nose one more time and pulling myself together enough to see the screen clearly, here I am. Counting the minutes until school starts, so I can tell students about this text. It’s the best feeling and it’s fueled by what I have deemed A Workshop Whirlwind.

book talk this story tomorrow, and how transformative I think this text could be for some of my kids, it’s what led me to this text that I find really important right now. As a result, approximately eight minutes after finishing that book, seven minutes after shoving a copy of it into my husband’s hands and insisting he “Read this. Read this immediately” (thankfully we’ve been married long enough that he can recognize a literary induced meltdown and not fear for his own safety), five minutes after texting half my department to tell them of my ugly-cry recommendation, and three minutes after blowing my nose one more time and pulling myself together enough to see the screen clearly, here I am. Counting the minutes until school starts, so I can tell students about this text. It’s the best feeling and it’s fueled by what I have deemed A Workshop Whirlwind. This summer, we’d like to

This summer, we’d like to

This summer, we’d like to

This summer, we’d like to