This past summer Shana and Jackie found that we’d both taken on a unique experiment within some of our classes–we had decided to strip them of whole class novels and instead focus on independent reading, book clubs, and smaller whole-class texts. As workshop teachers confident in the power of choice reading, we each felt that this shift would be both empowering and inspiring within our classrooms. After our year of experimentation, we both left our classrooms with unique perspectives on the power of whole-class novels as well as how we would incorporate them moving forward.

Over the next three days, we will post our insights and discussion we’ve had over the past week using Google Docs. Please, join the conversation in the comments!

Question 1: How did you decide to get rid of of whole class novels?

Question 1: How did you decide to get rid of of whole class novels?

Jackie: Last year I was faced with a unique opportunity: the English Department voted to end popular College Preparatory Advanced Composition course. Despite the well established curriculum, I tossed aside the typical whole class novels in favor of independent reading. As a primarily freshman English teacher, I am required to teach one Shakespeare play and To Kill A Mockingbird. Advanced Composition gave me the opportunity to focus on smaller whole class reads and mentor texts within daily writing workshops without devoting whole units to one book.

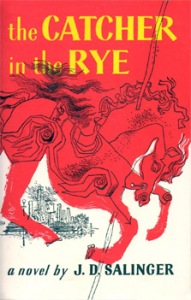

Shana: After six years of teaching, I wasn’t really sure why I felt compelled to teach whole-class novels. Every year, when I picked up Catcher in the Rye, I dreaded my job. I hated that book, and I had no idea how to get my students to love it or connect with it. It felt like a chore to drag my students through “reading” that text (mostly they were SparkNoting it, sometimes with the assistance of their football coaches–true story). I knew that not every student loved every novel that I did (particularly Their Eyes Were Watching God), and I knew that I didn’t love every novel my students read on their own (particularly everything by Nicholas Sparks). I started to wonder–what would my teaching be like if I didn’t feel compelled to teach a whole-class novel…merely because I should?

Jackie: The eye opening experience for me was definitely during my first year of teaching. I began integrating independent reading into my curriculum and I suddenly found out how many voracious readers I had in class. My teaching was getting in the way of these students’ education! I like how Shana puts it–I also knew that my students didn’t love the novels I did (Speak by Laurie Halse Anderson) and in the end, if I gave them freedom, I too would learn much more about literature, reading, and teenagers.

Shana: I like that Jackie mentions the issue of devoting whole units to a book–I loved having the freedom to design units of study that weren’t anchored around a novel, but rather a different genre.

Question 2: What were the positives of having no whole class novels and what were the negatives?

Question 2: What were the positives of having no whole class novels and what were the negatives?

Jackie: After a year, I have found both positives and negatives to removing whole class novels. Getting rid of whole class novels allowed me more time to focus on the positive aspects of the workshop model. Naturally student choice led to easier student buy-in, and I spent less time convincing students of the value of reading. As a result, we spent more time cracking apart smaller whole class reads like essays, poems, and articles and truly contemplating the author’s choices and craft. Additionally, I liked that I could assess students and discuss their growth based on their own reading goals and progress.

I have yet to find a solution to the “be on this page by this day” debacle that comes with teaching whole class novels. Too often whole class novels lead to less differentiation and more stress, which can lead to the “gotcha” feel that comes with discussing larger, longer texts.

That being said, there was a lot that I missed about having whole class novels. Losing a longer common text meant that students didn’t have the common classroom experience of connecting over both the successes and frustrations of working through a complex text together. I was surprised by how much students want to discuss their reading with classmates. While reading can at times feel solitary and maybe even isolating during the actual act, in reality, reading complex texts is a communal activity that unites groups through a variety of perspectives, opinions, and interpretations.

Shana: The positives were that I felt like my curriculum map was much more relaxed and flexible, in contrast to the years where I felt like I had to teach a minimum number of novels and “fit them in.” I also loved seeing my students’ love of reading skyrocket as they engaged in choice and challenges on only an independent or small-group basis.

The negatives were more nebulous–I just felt like something was missing. Our learners crave a challenge, and navigating a difficult novel is a challenge all readers relish if they have autonomy in their reading of that novel. Reading a novel together provides an opportunity for me to create instruction that scaffolds a student’s reading skills up to the level of that novel, allowing them to participate in a reading experience they may not have been able to enjoy otherwise.

I also really missed being able to ascertain the barometer of a class’s feelings on a certain theme or issue through discussions of a complex text. Crime and Punishment explores issues of morality, regret, and psychology in a far more complex way than “The Tell-Tale Heart” ever could, and although both stories have very similar themes, the novel lends itself to the sustenance of thought, evolution of a character, and length of a reading experience that I so craved for my students. I also think that some reading skills specific to stamina, fluency, and automaticity cannot be practiced or taught effectively without a lengthy text, so I felt that last year, my students missed out on practicing those skills.

Jackie: While we both feel similar in the value of whole class novels , I know that neither of us would return to a set list of novels. Whole class novels allow us to engage in common discussions but independent reading lays the groundwork for students’ stamina and confidence. I don’t start my first round of literature circles until the second quarter because of this. As much as students need a communal reading experience, I believe they first need a taste of independence and success.

Shana: I still haven’t figured out the whole reading schedule thing either, nor how to create buy-in for every single student so that they autonomously, independently want to read a novel. I struggle with the this-page-by-this-day conundrum, too, mostly because I feel like that creates a certain accountability that kids get hung up on, because it relates to the dreaded word GRADES.

More of our discussion will follow tomorrow. Be sure to join the conversation today in the comments!

Click here to read day two of our discussion.

Tagged: Jackie Catcher, novels, Shana Karnes, teaching novels, whole-class novels

[…] I committed to full-on workshop teaching, and that was the year I experimentally abandoned teaching whole-class novels, too. I liked a lot of the changes I saw in my students, but with my focus on how I was teaching, […]

LikeLike

At this point in my career, I’m not in the classroom, but I support teachers in a variety of settings. Because I’m a wild advocate of the workshop at the high school level (and at all levels), this conversation is one that strikes me as critically important particularly as I think about what I’ve learned from students. At one school — a school with highly educated and well to do families — I talked to students about To Kill a Mockingbird, a book they were reading in their 9th grade English class. They told me how much they hated it (arggghhhh! hurts an English teacher’s soul) and how they faked reading it. I then watched them in class, and it was amazing how clever the students were. Then in a school with students from poverty — lots on free and reduced lunch — the teacher told me how much students in one class loved The Bluest Eye. However, when I talked to students I found that some did love it, some faked it, and some didn’t even try to read it. These observations along with memories from my own classroom worry me. I’m looking forward to this conversation!

LikeLike

I’m not in the classroom but support teachers in quite a few settings. Because I’m a wild advocate for workshop in the high school (and at all levels), this has been an issue that’s been nagging at me for quite awhile especially as I watch and listen to students from all kinds of settings. I remember in one school with students from highly educated and fairly well to do families fake read To Kill a Mockingbird. If I hadn’t talked to the students prior to the class, I would never have known that they were faking it in their classroom discussion. And then in a high poverty school, a teacher told me how much students loved The Bluest Eye. However, when I talked to students, I found that some did, some faked it, and some didn’t even try. These experiences leave me quite cautious about units designed whole group novels. Still I hear some of my favorite teachers argue about the importance of shared reading, providing students from poverty with experiences similar to kids in the suburbs, etc. I so look forward to this conversation!

LikeLike

[…] Unlike Amy, I do teach whole class novels. Last year I experimented with teaching no whole class novels in my junior-level Advanced Composition course. […]

LikeLike

I’ve done a few things to address the problems you mention:

1. I organize book clubs around a common concept (e.g. “Power”). That way, we can discuss and do meaningful work as a whole class. Also, reading diverse books is actually a strength for these conversations, since there’s a lot that can be said about something like power.

2. Students choose into book clubs with a little bit of guidance. I create a flood of choices at 3 levels, for students who want (or should select) some challenge (adult or hard YA), students who should continue building momentum (most YA), and students who struggle to finish a book (high-interest YA).

3. To set up a discussion/due date schedule, I take reading rates from the students in each group and average it so everyone can keep up (if they read).

LikeLiked by 1 person

Jennifer, I agree: “reading diverse books is actually a strength for …[whole class] conversations.” I set up my book clubs in a similar manner. Works so much better than the struggle I used to have with engaging every student in a novel they had no say about reading. I love the average reading rate idea, too. It took me long enough, but I just figured this bit out this year!

Thanks for joining the conversation.

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] Click here to read day one of our conversation. […]

LikeLike

[…] is day two of our insights and discussion we’ve had over the past week using Google Docs (click here for day one). Please, join the conversation in the […]

LikeLike

This sounds like a fantastic plan! I look forward to hearing about your and your students’ experiences within the classroom. As you said, there does feel like there’s something missing, but that being said, there are so many other benefits you gain.

LikeLike

I love this and all of you!

I actually just blogged about moving from whole class novels into a reader’s workshop this year! I agree that without working with a longer, more complex text, it feels like there’s something missing from English class.

Instead of whole-class novels, this year I’m doing book clubs around genre. While we’re working with those books, my students are also reading their choice books for the first ten minutes, so they’re reading two books at once (one for “work” and the other for fun). So far, I’ve been really happy with what’s been happening in our class. We’ll do this three times this year, with a writer’s workshop and smaller texts interspersed throughout the rest of the year.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Your move to book clubs combined with independent reading is similar to mine. We learn much about reading literature and the skills needed to read complex texts in book clubs, and we learn stamina and fluency in the books we read independently. I also have students read thought-provoking short texts that they discuss in a Harkness-type setting — everyone must participate. This is usually where I get the most mileage in teaching analysis.

Thanks for your comment. Believe me, we love you, too!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I love this post. Due to logistical reasons, I cut down to one whole-class novel per year two years ago. I work in a small school (each class is no bigger than 8 students) and my students struggle with their mental health so students coming and going due to hospitalizations. And we didn’t have more than a class set so sending home books was dangerous (I’ve lost a handful of books before learning my lesson). Just by circumstances, I only teach one novel per year and not until the spring. And it makes a world of difference. The students have had enough time working with shorter texts that the novel is much more enjoyable and productive. Plus, with no curriculum requirements, I get to pick really high-interest books. We’ve read Among the Hidden, The Giver (with 11th graders… they had such a different perspective than the traditional middle schooler), Bruiser, Sold, and The Book Thief.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Rin, your experience reinforces how both diversifying and being selective about our whole class novels ultimately allows us to differentiate our teaching. Your classroom sounds like a prime example of what all students needing, especially those who might face additional challenges throughout the school year.

LikeLike

I would LOVE to follow this conversation via Google docs. Our teachers have made great strides related to independent reading, but we are still looking for ways to move more confidently in the direction of these dreams!

LikeLiked by 2 people